#Margaret Williamson

Text

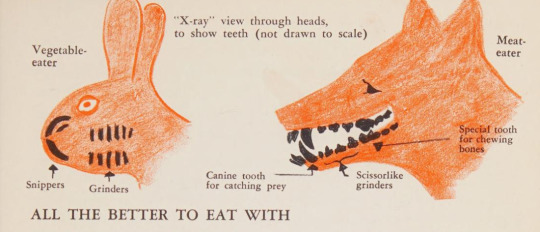

The First Book of Mammals. Written and illustrated by Margaret Williamson. 1957.

Internet Archive

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Public Square (the Terminal Tower) at 5-00, as seen through a Williamson building grill, Cleveland, Ohio

Margaret Bourke-White, 1928

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marion Gilchrist was born on February 5th 1864 she became the first female graduate of the University of Glasgow and one of the first two women to qualify in medicine from a Scottish university.

Born at Bothwell Park farm, South Lanarkshire to Margaret and William Gilchrist a prosperous tenant farmer, she had four older siblings; three brothers, John, William and Douglas, and one sister, Agnes. Her brother Douglas became was a well known agriculturalist.

Marion’s earlier education was at the local parish church when she was around 7 years old. She met with some challenges where her father and brother Douglas thought it pointless that she studied academic subjects however her brother John encouraged her and she attended the local primary school the Hamilton Academy before entering Glasgow University.

In 1887 she matriculated as an Arts student at Queen Margaret College in Glasgow. She completed her course in 1889 and enrolled along with thirteen other women in the newly opened medical school. She graduated in July 1894, the first woman graduate of the University of Glasgow.

She went into general practice developing an interest in diseases of the eye. The death of her father in 1903 allowed her to set up in practice at 5 Buckingham Terrace where she was to remain for the rest of her life. Financially and professionally independent, she became openly politically active. During 1903 she joined the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association for Women’s Suffrage. She did not take part in militant action, preferring to devote her voluntary energies to medical charities. In 1914 she was appointed assistant surgeon for diseases of the eye at the Victoria Infirmary. She resigned in 1930 as she found it difficult to combine the position with that of ophthalmic surgeon at Redlands Hospital for Women to which she had been appointed in 1927.

She was a prominent member of the British Medical Association and the first woman chairman of the Glasgow division. She had a fierce sense of duty which she expected others to share. When a newly qualified woman doctor was visiting her during the Second World War and the air-raid warning sounded, she told her young colleague that she must return at once to her hospital on the other side of Glasgow even though bombs were falling outside.

Gilchrist was an early motoring enthusiast and her garage and chauffeur’s house were situated in Ashton Lane, in premises which are now Bar Brel.

Marion Gilchrist’s achievements were honoured when her home town of Bothwell named Gilchrist memorial garden in her honour. The University of Glasgow named the Postgraduate Club after her. In 1932, a gift of £1,500 was used to endow a bed at Redlands Women’s hospital for the treatment of eye diseases which was also named in recognition of her.

The Gilchrist Window in the north transept of Bothwell Parish Church in her was created with funds she donated in 1936. The inscription below the window reads, “To the Glory of God. Erected by Marion Gilchrist in memory of her father William Gilchrist and her mother Margaret Williamson, her brothers, John William and Douglas, and her sister Agnes.”

The Marion Gilchrist Prize was established in 1952 from Marion Gilchrist’s bequest and is awarded annually by the University of Glasgow to “the most distinguished woman graduate in Medicine of the year.”

Gilchrist never married. She died at her home on 7th September 1952 aged 88.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brief history of wicca

A brief history:

Gerald Gardner, an English civil servant, novelist, and magician, is credited with establishing the religion that would become known as Wicca. Gardner, born in 1884, travelled much as a child and developed an interest in anthropology, archaeology, folklore, and, finally, spiritualism and other esoteric issues. He belonged to a number of groups and associations relating to his hobbies, including the Rosicrucian Order, which he joined in 1939. Gardner met other acquaintances who were members of an even more hidden inner group, and they confessed to him that they were a witch coven. He was inducted into the coven in September of that year.

Several years prior, in the early 1920s, a popular hypothesis circulated in anthropological circles about an old pagan religion that had been largely eradicated by Christianity but was still practiced in secret enclaves across Western Europe. Margaret Murray, the anthropologist who pushed the thesis, referred to the religion as a "Witch-cult," claiming that the remaining practitioners were organised into 13-member covens. When Gardner encountered the New Forest group, he knew they were one of the last vestiges of this old pre-Christian religion, and he intended to help assure the Witch-cult's survival into the twentieth century.

Throughout the 1940s, Gardner remained interested in a variety of religious and spiritual traditions and concepts, but his encounters with the New Forest coven had a profound influence. He eventually formed his own coven, Bricket Wood, and began to create a new incarnation of the ancient Witch-cult, drawing inspiration from a variety of sources, including the New Forest coveners, elements of Freemasonry and ceremonial magic, and the work of other occult figures such as Aleister Crowley and Cecil Williamson. Gardner's primary innovation eventually became one of Wicca's most fundamental elements: the worship of a Goddess and a God who were equal in every aspect. This was very unusual after millennia of male-dominated, patriarchal faiths!

Gardner never referred to his relatively young religion as "Wicca." He did occasionally refer to his coven members as "the Wica," an Old English name for sorcerers and diviners. However, the tradition was usually referred to as Witchcraft, or "the Craft," or "the Old Religion." It didn't become recognised as Wicca until at least a decade later, when it expanded to the United States and Australia.

By then, Gardner's disciples and other occultists had produced new versions on his idea, some of which bear little resemblance to the original Bricket Wood coven. In reality, many people in the UK who continue to practise Gardner's rituals as they have been passed down from covener to covener refer to it as British Traditional Witchcraft. These Witches see "Wicca" as something altogether distinct, often referring to it as an American creation. Gardnerian Wicca is the name given to the original version of Wicca in other parts of the world.

Although Gardner is regarded as the founder of the contemporary Witchcraft movement and was undoubtedly one of its most vocal public supporters, he clearly did not do it alone. Indeed, there are several notable personalities throughout Wicca's history. Many of his friends and colleagues participated in the partnership, including Patricia Crowther, Lois Bourne, and Doreen Valiente, as well as mid-century occultists Robert Cochrane and Raymond Buckland. Indeed, the complete history of Wicca and its growth may fill books, but the entire narrative would most likely never be recounted!

Furthermore, Gardner and others took inspiration from information, beliefs, and practices produced by various previous organisations dating back to the British occult resurgence of the late nineteenth century, and even earlier, to the thirteenth century. And those Middle Age occultists did, in fact, deal with ideas and materials from ancient civilizations.

So, even though no evidence for Murray's Witch-cult theory has ever been discovered, and no unbroken tradition of occult practice dating back to antiquity appears to exist, it is possible to argue that there was some kind of spiritual "lineage"—perhaps an eternal divine essence—strong enough to survive centuries of Christian dominance and reappear in modern times. Whatever the case, for individuals who practise Wicca, the experience is really timeless.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rating: G

Relationships: Larry West & Kilmeny Gordon, Larry West & Neil Gordon, Kilmeny Gordon & Neil Gordon

Characters: Larry West, Kilmeny Gordon, Neil Gordon, Margaret Gordon, Elizabeth Williamson

Tags: Alternate Universe - Magic, Alternate Universe - Fae, the orchard is actually magic and it might not be friendly, Emotional Manipulation, emotional abuse by a parent, Adopted Sibling Relationship, kilmeny and neil are actually friends

Summary:

For eighteen months, Larry West has taught school peacefully in the sleepy little town of Lindsay. A chance turn on a morning walk takes him to a place he's never seen: a hidden orchard tucked away in the woods behind town. There he meets Kilmeny Gordon, an enigmatic young woman hidden from the world and eager for company, and the two strike up a friendship. But all is not as it seems in the orchard, and soon visions of apple trees begin haunting Larry's every waking moment. Unnerving stories pile up: a promise made and broken with devastating consequences, a girl whose face is fair only within the orchard's boundaries. What magic is afoot, in this most unlikely of places? More urgently, what does it want with Larry?

For three and a half terms, Larry West has been master of the Lindsay school. When he accepted the position he had quietly resigned himself to two years of utter boredom and monotony. He doesn’t need much excitement in life, but Lindsay seemed unlikely to supply him with even that scant amount. Still, the president of the school board took his mission seriously and the pay on offer was generous enough that Larry couldn’t afford to turn down the position.

Now, after spending nearly two years in the community, he’s come around to the place. It’s quiet, yes, and the people are all solid, unimaginative folks. But their hearts are in the right place and they’ve welcome him with eager, open arms. He has the students – and their parents – figured out and the second year has gone even more smoothly than the first, now that he’s had a year to field test the curriculum and iron out the kinks. He’s getting to watch his oldest students prepare for adulthood, has gotten some letters from last year’s graduates that warm his heart, and there is a simple, quiet pride in seeing how little Joan Collier doesn’t struggle with her reading as much this year, or in watching Davey Miller go from 12 to almost 14 and stop tormenting his little sister quite so much. He’s fully expecting to finish out this year and teach one more before graduating himself and starting the rest of his life.

The Gordons, well, they don’t exactly derail all his plans.

It starts innocently enough. It’s early spring after a long winter and Larry is strolling through the woods near town on a Saturday, enjoying the fresh air. He doesn’t have a destination in mind, just a desire to stretch his legs and take in nature after so many weeks indoors. He’d caught a series of nasty colds over the winter months, and while he did appreciate the Williamsons’ attention and ministrations while he was ill, it’s a blessed relief to not have someone hovering over him every moment of the day.

He meanders along, taking this turn and then that, not really paying attention to where he’s going. The woods aren’t that large; he’s more likely to accidentally end up back in town than he is to get lost. The birds are in full song and the early spring sunshine creates dapples of light and shadow on the forest floor, so breathtakingly lovely that it takes his breath away a little. Larry was raised in a city and he is fully prepared to move back to one to marry Agnes and make his life working for (eventually – hopefully – with) her father in his business. It’s not that he would even really want to stay here in Prince Edward Island long term – kind hearts and good meals can only sustain him through monotony for so long. But for now, he appreciates the beauty around him with his entire heart.

He doesn’t realize he’s crossed from the woods into the orchard until he’s already well inside it. The trees thin out into regular rows, turning the sun’s light from chaotic golden patches into neat illuminated aisles. Spruces give way to apple trees, ancient and gnarled but unmistakable. The scent on the breeze changes subtly, from the sharp crispness of fir and spruce to a delicate, enchanting sweetness. It’s the smell of budding blossoms and newly grown grass and the two gloriously overgrown lilac bushes at the far end. Larry slows, looking around, uncertain how he came to be in such a place but delighted by it. A solid, ancient fence surrounds him – he must have missed it completely, lost in his thoughts as he’d been – and it’s clear that no one has tended to this place in a long time. It has grown wild, left to its own devices to feed birds and squirrels and fawns rather than men and machines.

The soft grass seems to beckon him, and he realizes with a start how long he’s been walking. After so many months of staying indoors and idle, the exercise has left him wearier than it should. He sinks to a seat at the foot of one of the trees, resting his back against the smooth bark. He’ll just sit down for a moment, to appreciate this unexpected secret just beyond the boundaries of Lindsay, and then he’ll be on his way, back to the Williamsons’ in time for tea.

By the time he wakes again it’s dark.

He doesn’t go back to the orchard again for several days after that. He submits humbly to Mrs. Williamson’s gentle scolding for being late and worrying her and sticks to walks that are closer to home for the rest of the week. But the orchard keeps tugging at the back of his mind, gentle but insistent, a constant background hum as he coaches the ten-year-olds through their sums and reads over childish compositions, squinting at the more creative approaches to spelling and wondering if he needs to put even more emphasis on penmanship next year. He journeys to and from the schoolhouse, blinking more often than usual to clear the memory of the orchard’s ancient trees from his vision. He studies his engineering texts as the ghost of the smell of lilac bushes floats by his face. The birds of Lindsay seem suddenly just slightly out of tune, their songs falling flat in comparison to the sweet melodies of their orchard-dwelling cousins.

When next Saturday rolls around, he packs a cold dinner and warns the Williamsons that he may be home late and not to worry about him. Mrs. Williamson watches him go with well-concealed concern; she knows better than most what it means to enter certain places, and she can only hope he’s not doing so uninvited.

It takes Larry longer than he expected to even find the orchard again. He hadn’t been paying attention last time, true, but it doesn’t seem like there should be enough distance between the Williamson home and the orchard for it to take almost two hours to go from one to the other. By the time he spies the silvery fence posts that have haunted his dreams he’s almost convinced himself that he imagined the whole thing.

But no. There it is, in all its glory. The sun is warmer today, and the apple buds starting to blossom fully. With not so much as a breath of wind to be found, the sweet scent hangs like honey in the air, heady and almost overwhelming. Larry quickens his step.

The grass beckons him again, but he resists its call for the moment. Instead he explores, treading every inch of ground, experiencing everything the orchard has to offer. He sees the places where the fence has fallen and the woods are starting to creep in, discovers the patches of violets sprinkled here and there amidst the grass, looks up and sees the bird nests tucked safely amidst the trees’ stately boughs. He knows without the slightest hint of doubt that he will never see any place so lovely ever again, even if he should live to be a thousand and explore every corner of the world.

Inexorably, the trees draw him back to them, and he finds himself once again sinking into the soft, fragrant grass beneath them. This time, he’s prepared for the way sleep overtakes him almost immediately.

He is not prepared to have company when he wakes.

For a moment, Larry thinks he is still dreaming. A woman – no, a girl still, with a girl’s innocence about her – stands a little ways away, clearly watching him. She has thick black hair, done up in two smooth braids, tossed carelessly over her shoulders. A few escaped wisps have been tucked behind her ears, brushing her shoulders. Wide blue eyes watch from a perfectly complected face, framed by delicate black lashes. In her hands is a violin, held with the ease of someone who considers it an extension of her own self rather than an instrument to be dutifully practiced.

She starts when she realizes Larry has woken and hides herself behind one of the trees. It occurs to Larry for the first time that the old orchard might be someone’s property.

Much embarrassed, he starts to get up. Of course someone would own the orchard – Lindsay is hardly a new settlement, and the fields around it have been well cultivated for generations. No doubt the owners of this orchard still love it fondly and come often. They must think it safe, to let their daughter go alone. And here he has blundered in completely uninvited.

He will ask Mr. Williamson about it, he decides, dusting the earth from his trousers. Mr. Williamson will know who owns this bewitching place, and he will give Larry guidance on how best to make his apologies to the family.

Before he can make his exit the girl emerges again, this time holding a little slate instead of her violin. With a determined look on her face she closes the distance between them and holds it up for him to read.

You don’t have to leave. I’m sorry I startled you.

Larry frowns. The message is clear, and the sentiment welcome, but the method of communication strikes him as distinctly unusual. Is she deaf? The violin would seem to suggest otherwise. But stranger things have been known to happen.

“Can you hear me?” he asks carefully.

She nods and erases the slate. A bit of chalk appears, with which she writes a new message. I can hear, but I can’t speak. I never have been able to.

Mute then, instead of deaf. That explains the slate, although not why Larry has never so much as heard of her before. Lindsay is not large; a girl this lovely should not have gone unremarked upon even without such a distinguishing feature as muteness.

“I’m sorry I trespassed onto your property,” Larry says, remembering his circumstances. “I didn’t even think to find out if anyone owned this place. It was so beautiful, I lost myself completely. I’m very sorry to have startled you.”

She smiles, and it’s like the morning sun clearing out the last of night’s shadows. It is beautiful, isn’t it? she writes. I was surprised to see someone else here, that’s all.

Her gaze is frank and open, with no trace of fear or malice to be seen. Larry knows he should leave anyway; even if she is the child of the orchard’s owners, it’s hardly appropriate for him to be alone with a strange young woman. No doubt her father would be far less sanguine about the situation, should he discover them – Larry has a good reputation in the community, and the fact that he has a girl back home is well known, but that won’t be enough to save either of them.

“I will take my leave,” he says, and tries not to let his reluctance to leave the orchard come through in his tone.

It doesn’t work. Her face falls. Oh must you? It’s not late yet and the days have gotten longer! Surely you can stay a little while?

Despite himself, he finds his heart going out to her. She must be very isolated, living so completely cut off from the rest of the town as she does. He can’t imagine what level of loneliness it would take to reach out like this to a complete stranger, to beg someone to stay after you found them trespassing. When was the last time she saw someone other than her family? Has she ever seen anyone but her family?

Against all his better judgment, he nods. “I suppose I can stay a little longer,” he says, and her expression brightens so much he nearly has to look away or be dazzled by its brilliance.

Oh I’m so glad! Mother always told me that all men were wicked, but you don’t seem wicked at all.

“I certainly try very hard not to be,” Larry says, and her shoulders shake with silent laughter. “I’m Larry West,” he continued. “I’m the schoolmaster at Lindsay. May I ask your name, Miss?”

I’m Kilmeny Gordon, she writes. Gordon. He knows that name. The Gordons keep to themselves, living outside of town and only setting foot in Lindsay to go to church on Sundays. They have a boy – a nephew of some kind – who sings in the choir and sometimes plays violin at the dances held periodically to entertain the young folk. Larry has never heard about a girl, mute or otherwise.

“It’s a pleasure to make your acquaintance, Miss Gordon,” Larry says.

She makes a face. Call me Kilmeny, please, she writes. No one ever calls me Miss Gordon. I don’t think I like being called that at all.

She really can’t have seen anyone other than her family, if she’s reached this age without ever being called anything but her given name.

“Do you come often to this orchard?” he wants to know.

Oh yes. It’s my favorite place in the entire world.

“It seems very old,” he says, looking up at the trees around them. “Does your family own it?”

She shrugs, as if she’s never even considered the idea before. I suppose. No one else ever comes here, at least. Just me. And Neil, but he’s family too. Do you know Neil?

“Not well,” Larry admits, trying to remember if he’s ever so much as exchanged words with Neil Gordon. “He sings in the church choir, doesn’t he?”

Yes, he has a lovely voice. Sometimes we try to duet, him singing and me playing, but it doesn’t work very well. I don’t know any of the songs he does and he’s not good at making up words to fit my melodies. She doesn’t seem upset by this; rather, it seems like a fond memory of two children playing together. Larry thinks of the few times he’s seen Neil Gordon, dark and withdrawn and aloof, and wonders what he must be like at home, to make this child light up so at the mere thought of him.

“Do you play often?” he wants to know.

Oh yes. Do you want me to play for you? It’s easier for me to let the music say what I want, than to write everything out on the slate like this.

“I would be honored if you would,” he says, and that’s all the prompting she needs to pull the violin out again and set it to her chin. Her eyes drift closed and, for an instant, she stands perfectly still, a snapshot of a girl frozen forever in place. Then the bow alights onto the strings and she begins to play.

Very rarely has Larry bemoaned his lack of artistic talent. Being mathematically inclined has always served him well, earning him distinctions in school and opening the door for a future engineering career that will hopefully be both lucrative and respectable enough to support Agnes Campion in the manner to which she is accustomed for the rest of her life. He likes the predicable nature of numbers, how no matter how often you turn your mind to a particular problem you will always get the same answer. They provide solace, amidst the uncertainty and turmoil that life can bring.

Listening to Kilmeny play, Larry feels acutely aware of his artistic shortcomings. If only he were a poet or a painter, maybe he could express the feelings that tumble through him at the sound. Or if he were a musician himself, he might know how to join in, to speak to her in her own language. But he’s only an engineer, and not even a fully fledged one at that, so all he can do is listen with his mouth agape as she stands next to him and music flows from her.

At last, she opens her eyes again and sinks to a seat next to him. She sets the bow and violin down on the grass and reached again for the slate. What do you think I said to you? she writes.

Larry gropes for an answer. He’d been so swept away by the music, he’d forgotten completely that this was her trying to communicate with him. No doubt she has a fully developed musical language all her own.

“I’m not sure,” he admits. “Although I don’t think you are unhappy?” It’s a guess, one based much more on their earlier conversation than the music itself. She laughs, that silent bobbing of head and shoulders.

I’m not, she assures him. I was telling you that I am glad you’re here and glad that it’s spring again. I was appreciating the beauty around us and how lucky I am to have someone to share it with today.

In the end, he stays longer than he planned, talking with Kilmeny and getting to know her. She’s charming, cheerful and eager for company. She wants to know about him and his life and he finds himself telling her his entire story, if in a slightly abbreviated form.

By the time he makes it back to Lindsay it’s dark. He hadn’t thought they’d spent that much time talking in the orchard – several hours, yes, but not the entire afternoon. But they must have, for the sun has set and Mrs. Williamson is giving him one of her scoldings, the ones that make him feel as though he’s a boy who’s disappointed his mother. He submits to it meekly, for he knows it is deserved, and resolves to stay away from the orchard from now on. The place is bewitchingly beautiful and Kilmeny made for truly delightful company, but its charms are not worth trespassing or upsetting his landlady, who has been so kind these past eighteen months.

True to his resolve, Larry keeps to town. He goes to school and pays calls on the parents of his students in the evenings. He plays checkers with Alexander Tracy and listens politely to old Mrs. Reid as she tells him yet again that he’s in consumption and should remove himself to the seaside immediately. On Sunday he pays special attention to Neil Gordon, singing in the choir, dressed in his best and outperforming every other singer without even trying. He does not dare approach the boy. Thomas Gordon has yet to descend upon the Williamson homestead to accuse Larry of trying to ruin his daughter, so Kilmeny must have kept their meeting to herself. Larry does not trust himself to match her discretion.

By Sunday evening, a headache has settled between his eyes and refuses to budge.

The next week is harder. He struggles to concentrate on anything. Memories of the orchard consume his thoughts. His headache stretches on and on, the pain gradually intensifying until it’s nothing but throbbing agony. He can barely sleep, but when he does he dreams of the orchard, of its sweetness and gentle loveliness. It would cure him, he thinks, even as he knows it’s irrational.

By Friday he can’t take it any longer. He closes school for the day, citing illness. None who have seen him this past week argue the point, and Mrs. Williamson tells him later that several parents sent word that if he needs to rest through Monday they will understand. He packs a cold dinner and heads out against the Williamsons’ wishes, assuring them that all he needs is some fresh air and quiet. It is not, he thinks guiltily, a complete falsehood.

It takes barely any time at all to find the orchard this time. He rushes through the spruce woods, barely noticing way the needles break the sunlight into a thousand patterns or the bustle of the squirrels in the trees or the newly sprung mushrooms decorating the forest floor. All he can think about is the orchard, and how sweet it will be to once more sink into the fragrant grass beneath the old apple trees.

Scarcely has he crossed the fence line when the tension in his head starts to fade.

By this point he’s prepared for the orchard’s odd soporific effect, and he welcomes slumber’s embrace eagerly. Scarcely has he settled into his usual place, nestled in the grass, back against the oldest tree, before his eyes fall closed. He sleeps deeply and without dreams, his fevered mind soothed by being once more in the place it has so fixed upon. When he wakes, Kilmeny is once again watching him.

This time, she doesn’t hide but instead joins him eagerly. They spend the day in easy conversation. Like before, Kilmeny is eager to hear about the rest of the world, her curiosity a seemingly inexhaustible well. Even the daily drudgery of the schoolroom fascinates her. A few questions from Larry reveal that Kilmeny has never gone to school. She learned to read and write at home, from her mother, and everything else she knows she has learned on her own, from books or conversation.

Neil shared his lessons with me sometimes, she tells him. But he wasn’t a very patient teacher, and anyway he didn’t want to do any more school than he had to.

So Larry pulls together some of his history lessons for older students and sketches for her the story of the country of her birth. She listens with rapt attention, by far the most diligent pupil Larry has ever taught. Before he knows it, he’s flown through an entire week of lessons and his throat is dry from talking.

My turn then, she says. What can I teach you?

He casts his eyes around, searching for a topic. “Will you tell me about this orchard? I’ve only known it in spring; what is it like during the rest of the year?”

Her face lights up. Yes! But I can’t do that with words. I’ll play it for you instead.

She sets the slate down and picks up her instrument. While Larry talked she had played the occasional chord, plucking at the strings or trilling a short series of notes – he surmised that this was her way of indicating agreement or question, the way he himself might hum or make some other noise while listening to someone else speak. But now she sets the violin to her chin and begins to play in earnest.

He tries to pay attention to the nuances of the music this time, to start deciphering her language properly. It’s a tall order. He thinks maybe he can grasp when she has fully changed seasons, when the bright chirping of spring becomes the languid lushness of summer, or when autumn’s minor key sighs turn to winter’s sharpness. But what she is telling him about flora and fauna, about the cycle of the trees and the lives of the creatures who live in them, that he can’t guess.

And yet, despite this barrier of understanding, somehow the soul of her communication reaches him. She plays the orchard in spring and he smells rich earth, newly wet from the storm. A vitality creeps into his bones, the promise of new growth after a long slumber. He feels, briefly and irrationally, the sudden intense urge for a child of his own to nurture and protect. As she moves into summertime the urge fades, and in its stead comes warmth as the sun’s intensity grows. He is in his prime, warm and well fed and bursting with vitality. Spring’s storms are but a distant memory and the ravages of winter too far into the future to concern him. Honey hangs thick in the air, and in the back of his mouth he can taste an impossible sweetness, as if the smell of the wildflowers had been given a flavor.

So swept up is he in the bliss of abundance that the first moaning chords of autumn cause physical pain in his heart. A shiver crawls up his spine, and a hunger settles into his belly. He must eat now, while there is still easy food to be found. His tongue yearns for apples and acorns to sustain him through the long winter ahead. Colors burst into his mind’s eye, brilliant gold leaves and russet apples, shining like beacons against the dusty green of the reliable spruce trees beyond the fence. The winds howl, rendered so lifelike by Kilmeny’s bow that Larry shivers and pulls his jacket tighter around him. Winter’s first snow falls like a shower of glitter, blinding him with sudden brilliance. Time slows to a crawl, and all his attention turns to staying warm and waiting out the cold.

When at last she lifts the bow from the strings and lets the last note fade into the air, Larry feels as though he’s lived an entire year.

Mrs. Williamson is waiting for him when he gets back to Lindsay, her husband skillfully banished somewhere else for the evening. She looks at Larry, sees him hale and bursting with life when just that morning he seemed to have one foot already in the grave. “Have a seat Master,” she says. “I think it’s time we talked.”

She asks if he’s been to the old Connors orchard and seems entirely unsurprised when he nods. Over the next hour, she tells him the story of the Gordons as she remembers it, tells him about old James Gordon and his children Thomas and Janet, about how they always seemed a little queer even before James’ second wife arrived. Good people, kind folk, but withdrawn. Kept to themselves and kept the traditions of the old country. Then came Bridget Gordon, James Gordon’s second wife. Young, fair, filled with light and laughter. She breathed life into the dignified solitude of the Gordon family.

“She had a way about her,” Mrs. Williamson says, her eyes distant. “Or so my mother said. Something that drew folk to her even when she was in a temper. And oh, what a temper she had. Her mood would change like the wind, my mother said, and you never knew what might set her off. But for all that she was kind and all three of the Gordons loved her dearly.”

Bridget Gordon lived only a few years in Lindsay before birthing her only child and dying from it. Margaret, the girl was called, and from her first days her brother and sister worshipped her. She had her mother in her, in looks and in temperament, ropes of long black hair and bright eyes that flashed as easily with laughter as with anger.

“We were friends,” Mrs. Williamson says. “Plenty of folks didn’t like her, strange and imperious that she could be, but those of us that loved her did so fiercely.”

It was Margaret who first brought Mrs. Williamson, then just plain old Elizabeth Mason, to the old orchard. They’d been sixteen and Mrs. Williamson had fallen in love for the first time.

“She made me swear that no man would ever separate us,” Mrs. Williamson says. She shivers a little, glancing around the room to ensure they’re still alone. “She took me into that orchard and had us clasp hands in the middle of it and swear. And Master, you know I’m a good Christian woman, and I was then too, but I tell you when we swore I felt something in the air. Something I couldn’t name and don’t care to. I don’t know what would have happened to me if I’d tried to break that promise, but it wasn’t just love for Margaret that made me loathe to find out.”

Larry thinks back to his time in the orchard, to the strange power it seems to have, to the way it invades his mind and soul whenever he’s not there. He has no trouble believing her.

A few years later, after a lifetime of not deigning to so much as look at any of the men chasing after her, Margaret went to teach school in Radnor and fell in love. All it took was one look, on both sides, and Margaret Gordon and Ronald Fraser knew they were destined to be together. Or so Margaret told Mrs. Williamson

“We went to the orchard again – we’d started going there often, to be alone and exchange confidences – and she told me that she’d found the one for her. I tried to talk sense into her. She hardly knew the man. He was a stranger in town, with no friends or relations to speak of. Here she was, she who’d never so much as looked twice at a man in her entire life, ready to wed a man she’d known for barely two weeks. I tried everything, Master. I argued, I bargained, I begged. Not to set him aside, you understand, but to give it some time to settle. ‘Have a long engagement,’ I told her. ‘Wait six months, a year. See if you still care for him, when the shine wears off. None of us would think less of you, if you decided to take it slowly.’ She wouldn’t hear of it. Oh, the things she said to me that day, Master, I can barely stand to remember them. And there, in that orchard, where she’d sworn just like I had to never let a man come between us.”

She shakes her head. The light of the lantern flickers, as if in some invisible breeze.

“Often I’ve thought, Elizabeth, you old fool, you knew better. You knew how stubborn she could be, and how proud. She’d cut her own nose off, if someone told her she was scared to. And maybe, maybe if I’d just held my tongue, she’d have come to her senses herself and not rushed into things. But after we fought about it, well, her pride wouldn’t let her back out. She and Ronald Fraser were married that very summer. We’d made up by then, she and I, and I was her bridesmaid at the wedding. What a sight she was, Master, the most beautiful bride you can imagine. She wore her mother’s dress, and I’ve never seen the like. Silk so soft you could barely feel it, and lace that must have taken a decade to make, delicate as a cobweb. She did her hair up in pearls and roses, and her bouquet was the reddest roses she could find. I’ve never forgotten the sight. If I close my eyes, I can see her right now, standing there that day, looking at Ronald Fraser like he hung the constellations in the sky just to please her.”

Margaret and Ronald Fraser were married less than a year before things went wrong. Ronald Fraser had told everyone he was a widower, and Mrs. Williamson swears she thinks he believed it. But whether he was wrong or lying, his first wife turned up in Radnor just the same. It broke something in Margaret. She packed her bags and went back home and never again left the Gordon farm. She received no visitors, sent no correspondence. It was like she had become a ghost haunting the town and, little by little, the town forgot her. Thomas and Janet Gordon weathered the storm, for someone had to make sure little Neil went to school and to church, especially with his unfortunate entry into the world. But Margaret stayed locked away, and her daughter Kilmeny with her.

“So there you have it, Master,” she says. “I won’t tell you that I believe our fight in the orchard caused all this misfortune to happen, but I know what I felt that day and I know what happened later. It’s a wicked place, Master. I won’t try to tell you not to go – I can see in your face that it’s no use even trying, and I won’t put you in a spot where you feel you have to keep secrets from me. But guard yourself. Don’t make promises there, no matter how sweetly someone asks you to. Don’t spend the night, and don’t eat the fruit from the trees.” She picks up her knitting, abandoned onto the table when she began her tale. “I’ve never told that story before, and after tonight I shan’t ever again. But you’re a good man, Master, and you’ve got a life waiting for you. I’d hate to see you trapped here.”

Mrs. Williamson’s words echo in Larry’s head long after the household has gone to bed for the night. He doesn’t believe in curses – or miracles, for that matter – and a young man and a young woman making foolish decisions in the heat of love and reaping the consequences is not a tale that requires any extra explanation. And yet, he can’t deny that there is something uncanny about the orchard, and about Kilmeny herself. Something unusual, something just a little too compelling. It’s unnatural, the way he can’t go for long without thinking of the orchard. And he can’t deny its healing power.

He’ll follow Mrs. Williamson’s advice, he decides, staring up at the ceiling and pretending he doesn’t see the ghosts of tree leaves superimposed onto the darkness. It’s entirely sensible to be wary of making promises and to avoid sleeping outdoors. As for eating the fruit, they won’t be ripe for months yet. Plenty of time to evaluate the situation and draw his own conclusions about things.

Over the next few weeks, he forms a new routine. He visits Kilmeny and the orchard twice a week, for a few hours on Wednesday evenings and all day on Saturdays. The rest of the time he tries very hard not to think about either of them. He gives his lessons and grades the homework and stays late after school to coach his older students in preparation for the Queen’s Academy entrance exams at the end of term. He visits with the Williamsons and pays calls on the parents of his students and stays up late into the night studying. He sleeps poorly, waking multiple times each night, and most mornings he emerges from his room with a headache firmly in place. He tells himself it’s the stress of working so much.

On Wednesdays and Saturdays, he makes his way to the orchard and all his troubles vanish.

Kilmeny is fascinated by the world, and so he takes to bringing some of his teaching textbooks along with him for her to read. She devours history and literature, makes annotations to his Nature Studies textbook, and wrinkles her nose at music and mathematics. What use has she for either, she asks him, when she can already do sums well enough to help her aunt Janet with the household accounts and when she taught herself to play the violin practically before she could walk? Larry tries to reason with her, pulls out his best lectures on the importance of learning as a tool of moral development, but Kilmeny proves as stubborn as her mother. In the end, Larry lets her have her way; she’s not one of his pupils, after all. He has no duty towards her save one of friendship, and he won’t test that bond over something as trivial as her lack of interest in algebra.

Most days, he brings his own work with him. He has too much to do to neglect it often, especially as spring creeps forward and the end of term examinations loom. Kilmeny, after glancing at his books a few times, has no interest. She plays for him, or wanders through the trees entertaining herself while he works.

Once, he asks Kilmeny if she would like to venture into town with him someday, after she has peppered him with questions about a dance that was recently held. Neil Gordon had provided the music, but evidently he doesn’t like to talk about his work with her and refused to answer any questions. Larry isn’t prepared for the look of utter horror that crosses her face.

No! She practically breaks her chalk in half as she emphatically dots the exclamation mark.

“Why not?” he asks. “No one would be cruel to you. Curious, I’m sure, but not cruel or wicked, especially not if you’re with me. My landlady, Mrs. Williamson, was friends with your mother, and I’m sure she’d be happy to make your introductions.”

Kilmeny is shaking her head. She retreats into herself, shoulders hunching protectively and head down so that her braids fall over her face. Larry sets his book aside, frowning.

“Kilmeny?” he asks gently. She doesn’t reply. “Kilmeny will you tell me what’s wrong?”

For a long moment, she doesn’t move, and he thinks she won’t answer at all. Finally, with hands that tremble and nearly ruin her penmanship, she writes, I don’t want to go anywhere. I don’t want people to see me.

“Why not?”

Because I’m ugly.

He stares at her. Looks down at the words again. Frowns. “Who told you that?”

My mother.

Why would Margaret Gordon have told her daughter such an obvious falsehood? Had she thought to spare Kilmeny her own pain, by dissuading her from going out into the world and having her heart broken? It was a cruel method, if so.

“Kilmeny, I promise you you are not ugly,” he says. “In fact, most people would say you are very beautiful.”

He expects an argument. What he gets is a silent puff of laughter, one that somehow conveys resignation despite its soundless nature.

You’ve only ever seen me in the orchard, she writes. Outside of it, I am very ugly.

“I don’t understand.”

She sighs, and finally looks up at him, her large blue eyes mournful gems in her perfect face. I don’t understand it, she writes. Her hand has steadied, and she writes with careful precision. But mother showed me when I was young. She had a mirror and we looked in it together, in her room. She breathes deeply as she erases the slate to make room for more text. It was dreadful. She was so beautiful and I was so ugly. Another pause. She rubs the words away particularly vigorously. She took me here and we looked again, and I was as pretty as her. And she told me that here, in the orchard, my ugliness would be hidden, but only here. She meet Larry’s eyes again for a brief instant. So you see why I won’t leave.

“How is that possible, that you should be ugly at home and beautiful here?” Larry wants to know.

She shrugs. I don’t know. But I’ve seen it and I know it’s true. Please don’t ask me to go out again.

Larry looks at her, sees the pain in her expression and the weight of old grief in her posture. It’s impossible, that a girl should look one way at home and entirely different in an orchard. But then, is it so much more impossible than an orchard that cures migraines or curses a woman for promises broken? Larry doesn’t believe in curses, but he knows when he is faced with something beyond his comprehension.

“I won’t,” he says. “I’m sorry I brought it up.”

You didn’t know. But let’s not talk of this anymore.

They change the subject. Kilmeny gets out her violin and plays her thoughts for him, challenging him to interpret her language. The sun rises high into the sky and starts its descent. By the time Larry returns to the Williamsons’ he has nearly forgotten the entire incident.

Next time he goes to the orchard Neil Gordon is waiting for him.

“Is something the matter?” Larry asks at once. He can think of several reasons Neil would be here instead of Kilmeny, and none of them are good.

“Kilmeny’s fine,” Neil says shortly, assuaging some of Larry’s worries. “I got Aunt Janet to keep her home this evening. We need to talk, you and I.”

“I don’t have any intentions towards her, if that’s what you’re worried about,” Larry says, the initial panic fading and wariness growing in its place.

“I know that,” Neil says. “I didn’t believe it, at first, but I’ve watched you and I’ve asked around and I believe you now.”

“Then what do we need to talk about?” Larry doesn’t like the idea that Neil has been spying on them, much less interrogating Larry’s neighbors about him behind his back.

“I believe you don’t have any intentions towards Kilmeny,” Neil repeats. His face is hard, determined, impossible to read. “But you need to stop coming here.”

“Why is that?” Larry demands, hackles rising. “I have her permission to visit. Are you that angry that she should have even one friend?”

“I don’t care about any of that,” Neil says. “If you really want to see her, you can come to the house and get Uncle Thomas to bring her down into the parlor. She won’t come, but you can try. But you need to stop coming to the orchard. It’s got its roots in you, I can tell, and you need to leave now, or you’ll never be able to.”

“I don’t understand,” Larry lies. He does understand. He knows deep inside him, with a cold certainty, that Neil is right, that all the things he’s been so steadfastly ignoring for weeks now are signs of some grave affliction in his soul that will only grow worse with time.

“Don’t you?” Neil wants to know. “Tell me honestly that you don’t dream about this place when you’re not here.”

Larry doesn’t answer. It’s as good as a confession.

“I’m telling you this for your own good,” Neil continues. “Trust me, I know how it is. Do you know how often I’ve tried to leave this town? I can’t, not after so long. There’s still time for you.”

Larry tries to pull himself together. It’s ridiculous. He doesn’t believe in curses. He doesn’t. Everything that’s happened can be explain somehow. Margaret Gordon’s ill-fated marriage was just a human tragedy, no more, no less. Larry’s own health problems are the result of working too hard, and the relief that the orchard provides him is just the result of being out in nature, of breathing fresh air and enjoying some pleasant company. As for Kilmeny’s belief in her own changing appearance, it can’t be as drastic a difference as she believes. It must have been a trick of the light, or some distortion in the mirror that her young mind twisted into impossible proportions.

“I don’t believe you,” he finds himself saying, and Neil’s face contorts into an ugly scowl. “I think you’re jealous that Kilmeny has a friend other than you and you want to chase me away. Are you in love with her, is that it? Do you want her all to yourself? Or are you just scared she won’t pick you, if she meets anyone else?”

“Shut up,” Neil snarls. “You don’t know anything. Of course I love her. She’s like my sister. I was four years old when her mother came home, did you know that? When that witch spat in her own father’s face and killed him with her silence. I’ve known Kilmeny her whole life and there’s no one like her. And I’m not scared of anyone. I came to help you out, but I guess you’re too good to listen to someone like me.” His hands clench into fists. “When you try to leave and can’t, don’t say I didn’t warn you.” He turns to leave, anger in every line of his body.

“Wait!” Larry says. “What do you mean, Margaret’s silence killed her father?”

“Ask Aunt Janet yourself, not that she’ll tell you.”

Larry takes a breath. Then a second. He needs to calm down. His head is swimming with feelings he can’t even recognize, and he knows he’s being irrational. Being told not to come back to the orchard has sent a deep, primordial panic coursing through him and there is just enough rationality left to him to recognize that this isn’t right. “I’m sorry,” he says, forcing the words out one at a time. “I didn’t mean to say those things. I don’t know what came over me.”

Neil pauses, turns back to look at Larry again. Whatever he sees in Larry is enough to take the edge of his anger. “I do,” he says. “But never mind. Let’s talk somewhere else. Do you drink, Master?” There’s a bite to the way Neil pronounces the title, a bitter sarcasm that Larry forces himself to ignore.

“Some,” he says.

“Come on then,” Neil says, and Larry follows him away from the orchard in silence.

In silence Larry follows Neil to what he assumes is the Gordon homestead, and in silence watches as Neil hitches the horse up to an old wagon. In silence, they start away from the homestead, the horse’s hooves unnaturally loud in contrast to the stillness of the wagon’s occupants.

Larry tries to collect himself as they drive. He doesn’t know what came over him, back there. Just a hazy cloud of unfiltered emotions. He can only think of one other time when he’s felt that kind of intensity, and it gives him pause. Has he fallen in love with Kilmeny after all?

He examines the question, turns it over and over in his mind, dreading the answer but needing to know. Has Agnes Campion, for so long the flame he has kept burning in his heart, been replaced without his even realizing it?

But no, that’s not it. When Larry thinks of Kilmeny in isolation, he feels nothing but friendship for her. He thinks on her face, impossibly lovely but provoking no deeper feelings within him. And then he remembers Agnes, thinks of her as he saw her last, and feels the familiar sensation of longing stir within him.

And yet, when was the last time he thought of Agnes before now? He has a letter from her, a month old at least, waiting unanswered in his room. He keeps meaning to get to it, but some distraction always seems to come up.

That’s not right. It’s not some distraction. It’s the same distraction, every time. And it’s not Kilmeny, no matter how sweet her face or pleasant her company.

A weight settles deep inside him.

Neil drives the horse easily, clearly guiding it down a well known course. They’re going to Radnor, Larry realizes after a time. Far enough away that it’s unlikely any of their neighbors should notice or overhear them. With what their conversation is likely to be, Larry can only be grateful.

Eventually, Neil starts to hum to himself, a song Larry doesn’t know. Around them, the sounds of evening join in harmony, crickets and rustling leaves and the steady beat of the horse’s hooves. Larry thinks of Kilmeny’s uncanny skill with the violin and the weight in his belly grows heavier.

At last they pull into Radnor and Neil directs the horse towards an unimposing building. “We’ll be left alone here,” he says shortly. “The barkeep’s a friend of mine.”

It seems like a bad time to voice the observation that Larry didn’t think Neil had any friends. He waits while Neil ties up the horse and the two men step inside. It’s dim and hot, smoky from half a dozen pipes and twice as many cigarettes, but clean and not as loud as Larry feared. The man behind the bar greets the two warmly.

“Give us a booth Jack,” Neil tells him, the most at ease Larry has ever seen him. “Master West and I have some business.”

“I’ll be sure to keep your throats nice and lubricated then,” Jack the barman says with a grin, and directs Neil and Larry to a booth in a discreet corner of the bar. When he’s brought them their drinks, Neil at last turns to face Larry once again.

“Feeling better?” he asks.

“Yes,” Larry admits. He wouldn’t say he’s feeling well, but the fog of emotion has lifted somewhat, cleared by the journey. Cleared, he thinks unhappily, by putting some distance between himself and the old Connors orchard.

“Tell me what you know about our family,” Neil orders. Larry recounts what Mrs. Williamson told him, leaving out the promise she and Margaret had made or the fight they’d had about Margaret’s marriage. Neil doesn’t interrupt, just sips his drink silently as Larry talks. There is an uncomfortable intensity in his gaze, one that makes Larry want to squirm like a young child caught in misbehavior.

When he finishes he takes a long swallow of his own drink, just for the excuse to look away.

“I never knew Grandmother Bridget,” Neil says. “You know, I assume, how I came to live with the Gordons?”

Larry nods.

“I barely remember Aunt Margaret before she married. She never liked me anyway. But Aunt Janet told me often enough that she was the spitting image of her mother, in good and bad. And Aunt Margaret was –” he pauses, searching for the right words “—different. I didn’t learn the word for it until I was twenty and she was dead, but I’d always known, somehow.”

“What word?” Larry whispers.

“Fairy,” Neil says, the word falling so matter of factly from his lips that Larry can’t even begin to object. “From the old country. I don’t know if Grandmother Bridget was full fairy or not, but she must have been pretty close to it, with how much of the magic Kilmeny still has. I don’t think Aunt Janet and Uncle Thomas have any of it in their blood, although they’ve lived alongside it long enough that they’ve picked some up, same as me.”

He's looking directly at Larry, daring him to object. And Larry wants to. It’s ridiculous. Fairies are creatures from story books, fanciful tales used to entertain and to frighten children into saying their prayers and putting their shoes away at night. But the words stick in his throat, unspoken. It’s impossible. It explains everything. He doesn’t believe it. He can’t help believing it.

“Does Kilmeny know?” he asks instead, because he has to ask something.

“No, unless she’s guessed on her own. Aunt Margaret forbade Aunt Janet and Uncle Thomas from telling her anything. Said she’d tell Kilmeny herself when she was old enough. But then Aunt Margaret died without saying anything, and Aunt Janet and Uncle Thomas are too scared of her ghost to defy her, even now.”

“What does this have to do with the orchard?” Larry wants to know. “Are you saying that Margaret put… some kind of magic on it?” He feels impossibly stupid, saying the word aloud.

“No, it’s older magic than that,” Neil says. “I think it’s older than Grandmother Bridget even, although she’s the one who noticed it first. She was good friends with Mrs. Connors, and when their house burned Grandfather bought the orchard in her memory. It wasn’t so wicked then, though.”

“What happened to it?”

Neil shrugs. “Who knows? Time, or sorrow. Aunt Margaret always used to go there, maybe she did something to it. But even before it was wicked, it was strong. Do you think it was a coincidence, that the Connors’ livelihood burned the very day they started talking about retiring to town?”

“You can’t mean to say that the orchard caused their house to burn!”

“Can’t I? It has a will of its own, that place, and it doesn’t like when people try to leave.”

Despite the warmth of the room, Larry shivers.

“You said you’ve tried to leave Lindsay and can’t,” he says. “What do you mean by that?”

“It’s always something,” Neil says. “The first time I was fifteen. I’d had a fight at school and Uncle Thomas blamed me for it.” His face twists in memory, the anger clearly still close to his heart. “We fought, him and me, and I stormed off. I was old enough to work, and I swore I’d never come back. I got as far as Radnor and got so sick I couldn’t go any farther. They had to drive me back home because I couldn’t even sit on a horse. When I was seventeen I signed on to work on the docks, out at the port. When I got there, they said they’d lost my contract and I didn’t have a job after all, and the boss threatened to set his dogs on me if I didn’t get out of his office. The last time I tried to leave was when Aunt Margaret died.” He closes his eyes, taking a long, fortifying drink. “The train derailed ten miles out of town. Worse accident in a generation. Killed twenty people. No one knows what happened.” His dark eyes blaze as he meets Larry’s gaze. “Except me. I know. I haven’t tried again. My freedom’s not worth getting others killed over.”

Larry doesn’t even try to say it might all have been coincidence. He’s too busy being horrified, first at the destruction and then at the implications for Neil’s life. He’s wondered, once or twice, why Neil didn’t just leave town, with how poorly everyone in Lindsay talked about him. Apparently now he has his answer.

“Don’t waste your time feeling sorry for me,” Neil snaps. Larry’s thoughts must be clear on his face. “Worry about yourself instead. You see why I told you to leave now? Unless that girl of yours is willing to come live here with you instead, you need to get out soon. You haven’t eaten any fruit yet; the hold it has on you will fade when you’ve put some distance behind you.”

The fruit. Mrs. Williamson had mentioned it too. Larry swallows. “Thank you for telling me,” he says. His throat feels dry despite his nearly empty glass.

Neil snorts. “Don’t mention it,” he says. “I’m doing it for Kilmeny anyway. She likes you, you know.”

Larry tries to ignore the heat rising into his face. “Say,” he says, groping for a distraction. “Kilmeny told me she thinks she’s ugly everywhere but the orchard. You’ve seen her at home – is it true?”

“No,” Neil says. “But it’s more complicated than you think.” He sighs. “I need another drink for this. You want one?”

Larry shouldn’t. He doesn’t drink often, and there’s school tomorrow. He can’t even imagine the scandal if the schoolmaster should turn up hungover. He nods. Neil grabs both glasses and slips out of the booth. He makes laughing small talk with Jack the barman and soon enough comes back with two new drinks, filled so full the liquid spills over onto the table when he sets them down.

“Aunt Margaret never liked that Kilmeny’s pretty,” Neil says, when he’s settled back into his place. He eyes the drink warily, judging if it will spill over him if he picks it up. “Used to say that the only thing being pretty ever got her was into trouble, and that Kilmeny’d be better off if she was hideous.”

“That doesn’t seem fair,” Larry objects. He takes a careful sip of his own drink, the cold liquid warming his belly as he swallows.

“That was Aunt Margaret,” Neil says. “Fair never came into it. She told Kilmeny that she was ugly so that she’d never want to leave home. For a while it was enough – between that and her not being able to talk she didn’t want to go anywhere. But you know her. She’s curious about everything. She started pestering Aunt Margaret to let her go into town, just to see what it was like. So Aunt Margaret cursed the mirror.”

Larry blinks. “She what?”

“She threw out all the mirrors in the house except hers and did magic on hers so that it would make Kilmeny look ugly,” Neil repeats. “Don’t ask me how, I don’t know and I don’t want to. But I know it’s true. Kilmeny showed me herself.”

“So when she looks in the mirror she sees herself distorted?” Larry asks. Neil nods. “Why did Margaret let her see her true reflection in the orchard then? Why not make her think she’s ugly always?”

“I suppose even she couldn’t bear seeing how much it hurt Kilmeny to think she was so ugly,” Neil says. “Or she wanted to bind her even closer, just in case. Or the orchard couldn’t abide by a magic that was stronger than it and broke the curse.” He shrugs. “Whatever her reasoning, it worked, didn’t it? Aunt Margaret’s been dead for three years and Kilmeny won’t set foot outside, no matter how much anyone begs her to.”

“Surely you’ve told her that the mirror is wrong?”

“Doesn’t do any good. Her own mother laid that curse, and told her it was the truth. Wouldn’t you believe your mother over everyone else, if it came down to it?”

Larry considers. His mother is a gentle woman, a widow doing her best to provide for herself and her only child. She would never lie to him like that, no matter how much she disagreed with his choices. “I suppose I would,” he says, reluctant.

Neil says nothing, his point already made. For a time, they drink in silence. Finally, Neil leans back in his seat. “I suppose I should say this part,” he says. “I’d be much obliged if you kept this all to yourself.”

Larry can’t help it. He snorts. “Don’t worry,” he says. “I’m not about to go telling everyone about magic orchards and fairy curses. They’d dismiss me in an instant for being raving mad and I need the money.”

Neil grins, and it’s the first genuine smile Larry’s seen from him. “They would, wouldn’t they?” he says. “I forget how it all sounds to outsiders sometimes.”

“I suppose when you grow up with something it all starts to seem normal,” Larry says, and Neil nods.

“Finish up your drink, Master,” Neil says, and somehow the word doesn’t sound nearly so bitter this time. “I think it’s about time I get you home, before the Williamsons start accusing me of making off with you.”

“They’re used to me being home late on Wednesdays,” Larry says, but he finishes his drink in a long swallow. His head spins pleasantly, not enough to impact his balance but enough to take the edge off the world.

Neil settles the tab on their way out. Larry tries to pay for his share, but Neil won’t take any money from him. They ride back to Lindsay mostly in silence, but it’s a comfortable kind of silence this time, the anxieties and uncertainties of the trip out smoothed by conversation and by alcohol. Neil hums to himself again, and Larry lets his mind wander, and by the time they pull up to the Williamson’s home, Larry finds himself regretting that it’s taken this long for him to get to know Neil Gordon.

“See you around, I’m sure,” Neil says.

“Say,” Larry says, halfway out of the wagon, struck by sudden inspiration. “I want to go to the orchard one last time, to say goodbye. Do you want to come along? I know Kilmeny would be glad to have you.”

It’s too dark to see the expression on Neil’s face. For a long moment, he says nothing. Then, just as Larry is about to give up and finish exiting the wagon, Neil says, “Sure. For a little while maybe. For Kilmeny’s sake.”

“For Kilmeny’s sake,” Larry repeats, laughing a little. He’s still smiling when he makes it inside.

Thursday and Friday inch by. Larry isn’t hungover, as it turns out, but he might as well be. The usual longing for the orchard is eclipsed by a new set of worries, worries about how Kilmeny will take losing her only friend, worries about what he’s going to do if he has to leave Lindsay, worries about how on Earth he is going to explain any of this to Agnes. Come Saturday morning he’s up at dawn. Pacing will wake Mr. and Mrs. Williamson, whose bedroom is directly beneath his, so he sits on the bed and forces himself to wait patiently until he hears movement downstairs. It’s agonizing.

Finally he hears the tell tale sounds of Bob Williamson getting ready to start his day. That’s enough for Larry. He puts his clothes on in a hurry and makes his way down to the kitchen. Mr. Williamson is there making coffee, still unshaven and in stocking’d feet, Timothy relaxing in an early morning sunbeam.

“Morning Master,” Mr. Williamson grunts, clearly still partially asleep. “Coffee’s not ready yet.”

“That’s all right,” Larry says. He makes his way to the icebox, pausing to administer scratches to Timothy along the way.

“You’re up early. Couldn’t sleep?”

He hadn’t slept well at all, in fact, but Larry only shrugs. “I was awake,” he says. “Thought I’d come down here, now that you’re up as well.”

“Suit yourself,” Mr. Williamson says. On the stove, the coffee has started boiling gently.

Larry eats his breakfast and drinks his coffee, grateful that Mr. Williamson is only loquacious after ten in the morning. There’s no way he could maintain any kind of façade that everything’s fine this morning, and the last thing he needs is for kind-hearted, gossipy Mr. Williamson to notice that something’s wrong.

Finally, when he can bear it no longer, he packs up some provisions and makes his excuses and heads off for the old orchard. He’s early, but that’s all right.

Despite the early hour, Neil has beaten him to the orchard. He’s standing with his back to the fence, looking at the trees, but he turns when Larry hails him. There’s an odd blankness to his face, as though he too slept poorly last night.

“I wasn’t expecting you so early,” Larry says.

Neil shrugs, a little stiff. “Didn’t see any point in wasting time,” he says.

Looking around, Larry notes that Neil is alone. He frowns. “Where’s Kilmeny?” he asks.

“She’s coming,” Neil says. “She had some things to do at home this morning.”

Larry nods. They lapse into an uncomfortable silence. Larry is rapidly regretting inviting Neil to join them. Wednesday night, in the heat of the moment, fueled by emotion and drink, it had seemed such a good idea, but now in the cold light of morning he thinks he misjudged. Perhaps there’s a reason after all that it’s taken him this long to talk to Neil Gordon.

Neil turns back towards the trees. Larry stands awkwardly near the fence, his pail still in his hands like a schoolboy.

Time stretches on. Larry ventures further into the orchard and settles himself as best he can. He wishes Kilmeny would arrive. She would smooth things over, surely. She knows Neil far better than Larry, and she has a way about her that puts people at ease. But Kilmeny doesn’t come and, when Larry checks his watch, he sees it’s only been a few minutes. It feels like hours have passed.

“Say,” Neil says, and Larry looks up with a start. He hadn’t heard Neil approaching at all, yet the man now stands directly above him. He’s holding something in one hand. “Do you want some breakfast?” He offers something to Larry. An apple.

Larry’s about to refuse it, to politely explain that he’s already had breakfast thank you, then thinks better of it. Clearly Neil finds this whole thing as awkward as he does, if his stiffness is any indication. Larry won’t make the situation worse by refusing what is clearly a peace offering. “Thank you,” he says, taking the apple. It’s lovely, perfectly ripe and inviting. He hadn’t been hungry at all a moment ago, but the sweet smell of the apple fills his nose and he finds his mouth watering. He takes a bite. It’s impossibly delicious.

Next to him, Neil cries out in dismay.

Too late, Larry realizes what he’s done. It’s far too early for apples. In this place, that can only mean one thing. He spits out the mouthful of fruit, horrified, the sweetness turned to ash in his mouth, but it’s too late.

Anger fills him. “What have you done?” he demands, rising to glare at Neil. “Why?”

Neil won’t meet his eyes. Larry throws the rest of the apple onto the ground and looks past Neil, towards the tree the boy has been watching. He sees now what he hadn’t noticed earlier – somehow, despite its age, despite the season, the tree is laden heavy with fruit, hundreds of russet apples all perfectly ripe. If Larry hadn’t been convinced of the orchard’s magic before, this sight is enough to settle any lingering doubts.

“Why?” he asks again. “Answer me!”

Still, Neil says nothing. Anger courses through Larry. He finds his hand raising, as though to strike Neil, and forces it back down.

Behind them, someone laughs.

Larry whirls. For an instant, he thinks he’s dreaming. Kilmeny stands between the lilac bushes. No, not Kilmeny. This woman is older, her face harsher, and there’s no violin to to be seen. She wears a dress of emerald green, its style several years out of date. And she’s laughing. Out loud.

“Don’t blame him,” she says, her voice low and musical and brimming with what Larry now recognizes as magic. “He couldn’t help it any more than you can.”

“Who are you?” Larry asks, even as the answer comes to him. There’s only one person this could be, impossible as it is. He’s not surprised when she answers.

“Forgive my rudeness. I’m Margaret Fraser.”

“Pleased to meet you,” Larry says automatically, because his mother raised him to be polite and he’s too busy trying to figure out what’s going on to think better of it.

She laughs again. Distantly, Larry thinks he understands why Mrs. Williamson loved her so fiercely, so many years ago. “Oh I see why she likes you,” she purrs. “But it’s too late. You should never have come here.”

Next to him, Neil is looking at the ground, misery radiating off of him. He must have been enchanted, or compelled somehow, when he gave Larry the apple. Certainly he can’t be working with Margaret by choice, not after what he said about her the other night.

“Come here,” Margaret orders, the laughter gone from her voice. Larry doesn’t want to obey, but to his horror his body moves of its own volition, closing the distance to stand before her. “Look at me.” He does. Up close, she looks nothing at all like her daughter, despite the similarities in their coloring. Where Kilmeny is laughter and innocence, Margaret is sharp edges and harsh corners. Her blue eyes, the same shade as Kilmeny’s, are hard and glittering, not a speck of warmth to be seen. She scrutinizes him, her gaze stripping him down to his very soul. He feels exposed, judged and found wanting, the worst examination he could possibly imagine. “Hmph,” she says. “Not much to look at, are you.”

Larry wants to be offended – he’s not the finest example of male beauty, sure, but he fancies he cleans up well enough – but there’s no room in his heart for anything but fear. Margaret is looking at him not like an examiner, who has tested a pupil and found them lacking, but like a hunter, sizing up their prey to see if it’s even worth bringing home.

He knows instinctively that, no matter what she finds in him, he’s never going home again.

“What do you want?” That’s Neil, anger fighting with despair in his voice. He’s braver than Larry; Larry couldn’t imagine speaking to her in that tone. She’d eat him alive if he even tried.

Margaret’s face curls into an expression of distaste. “I don’t need you anymore,” she says, and makes a shooing gesture with one hand. “Go on now, before I forget that my father loved you.”

Larry tries to call out to Neil, to urge him to save himself while he can, but his throat won’t obey him any more than the rest of his body will. He’s stuck, a prisoner inside his own flesh, unable to do anything but watch the world in unblinking horror.

“What are you going to do to him?” Neil asks. Again, Larry tries to yell for him to leave. Again, the words stick in his throat.

“He’s going to serve as a lesson for my dear daughter,” Margaret says. “She’s gotten bold, now that she thinks I’m gone. I told her very specifically not to associate with men.”

“You’re dead,” Neil says. “She doesn’t have to listen to you anymore.”

Margaret’s features contort with anger. “You will be silent,” she snaps. Neil doesn’t reply. Has he come to his senses? Or has Margaret stolen his voice like she’s stolen Larry’s?

Margaret turns back to Larry. He would shrink under the power of her icy gaze, if he could just regain control over his own body. “Follow me,” Margaret orders and, like a marionette, Larry does. Margaret leads him to one of the trees – the one Larry has come to think of as “his”, and why does that feel like a betrayal? – and makes him sit beneath it. She arranges his limbs one way, then another, posing him like a doll until she is satisfied with the picture he presents.

Neil still stands rooted in his spot, pale and shaking with anger. “You won’t get away with this,” he says, his voice straining with effort.

Margaret’s eyes narrow. “I thought I told you to be silent,” she says.

“You don’t have power over me, not anymore,” Neil says, but he’s sweating. Fighting the magic? Or just so overcome by emotion? “I’ve gotten stronger, while you’ve been dead.”

Her face transforms with anger, and Larry wonders distantly how he could ever have mistaken this woman for Kilmeny. He expects her to sprout fangs and claws, so inhuman does she look in her fury. “Watch your tongue,” she snarls. “You know nothing of power, and you never will.” And the air around her seems to shimmer, like she has cloaked herself in haze. Larry hadn’t thought it was possible for him to feel more afraid than when she looked at him directly; he’s wrong.

Neil doesn’t reply. He’s pale as death, drenched in sweat and trembling like a leaf. The tiny corner of Larry’s heart that isn’t overtaken by bone-shaking terror fills with admiration for Neil’s stubborn courage. But it’s clear that he will not win this confrontation. Margaret takes a step towards him; he stumbles back and she laughs. It’s a cold, cruel sound, a laugh of mocking victory with not a trace of mirth to be found.

It's then that the worst sound yet reaches their ears. A violin, played merrily by someone approaching the orchard. Kilmeny. Kilmeny, who doesn’t know what’s happened. Kilmeny, who will be as trapped as Larry and Neil if she crosses the orchard’s boundary. Larry tries to yell, tries to wrench himself free from Margaret’s trap the way Neil has, but it’s useless. No matter how he tries, his body will not obey. He turns his thoughts to the sky, prays as he’s never prayed in his life, begs God in His Heaven to turn His attention to this orchard and set them free.

God in His Heaven does not hear.

Neil makes a strangled noise, like he too is trying to yell. It’s not enough. The music comes closer and closer. Margaret waits with a smile. Larry wants desperately to squeeze his eyes closed, to turn his face away, to put off the inevitable a scant few seconds longer. He watches frozen inside himself as Kilmeny steps into the orchard.

Her music ends with an abrupt screech as she almost drops her bow in surprise. She takes in the scene before her: Larry sitting statue-still under the apple tree, Neil white and trembling, and Margaret. Margaret who should be dead, standing easily in the very center of the orchard, looking directly at her daughter.

“Hello Kilmeny,” Margaret says, and Kilmeny shivers. “It’s been a long time.”

With a trembling hand, Kilmeny puts her bow to her violin again and plays a string of notes. For the first time, Larry understands their meaning immediately.

“Mother?” the instrument asks.

“Yes child,” Margaret says. She holds out her arms. “Come, kiss me. I’ve missed you so much.”

Kilmeny takes a step towards her, then another. Then she stops. Looks at Neil and Larry with a frown. Even without playing a note, her meaning is clear.

“I’m afraid you need to be reminded of the lessons I taught you,” Margaret says. “These generous friends of yours have offered to help.”

Kilmeny plays another string of notes. Again, Larry grasps their meaning effortlessly. “I don’t understand,” Kilmeny says.

“Don’t you remember what I told you about men?” Margaret asks.

A flurry of notes, discordant and confused. “You said they were wicked and dangerous. But Mother, Larry and Neil aren’t wicked! Neil has been my friend my whole life, and Larry has been so kind to me!”

Margaret shakes her head, the picture of a mother patiently explaining something obvious for the dozenth time to her somewhat backwards child. “I’ve told you before, even the most wicked men can be kind to you until they get what they want. You can’t trust them, even when you’ve known them your whole life.”

Kilmeny casts her eyes towards the ground unhappily. When she puts her bow to the strings again, the notes tremble. “I don’t think either of them wants to hurt me.”

Margaret frowns. “Haven’t I told you before not to talk back?” she asks. Kilmeny nods mutely. Margaret’s face softens again. “You’re still young,” she says. “And you’ve had to go so long without me to keep you safe. I forgive you for forgetting what I taught you.”

It’s Kilmeny’s turn to frown. “Aunt Janet keeps me safe,” she says. “And I’m not a child anymore, Mother.”

“Janet does her best,” Margaret agrees. “But darling, you don’t know how young you still are. Trust me, I only want to make sure you never get hurt as I did. You can’t blame me for wanting to spare you my pain, can you?”

Kilmeny shakes her head, but she’s still frowning. “I don’t think they would hurt me.” There is a firmness to the notes, like she has found a core of resolve amidst the turmoil of emotions. “What have you done to them?”

“They’ve trespassed,” Margaret says. For the first time, she seems slightly out of her depth, as though she was unprepared for Kilmeny’s stubbornness. Death must have impacted her memories; Larry could have told her himself that once Kilmeny gets a notion into her head nothing can sway her from it, and he’s known Kilmeny less than two months.

“I asked Larry to come here,” Kilmeny objects. “And Neil’s family.”

“He is not your family,” Margaret snaps. “I don’t know how many times I’ve told you that, Kilmeny,”