#Flip Schulke

Text

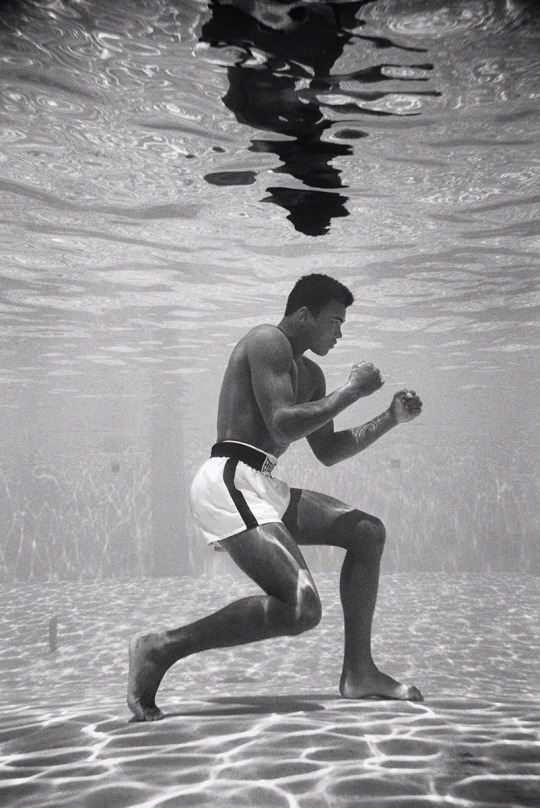

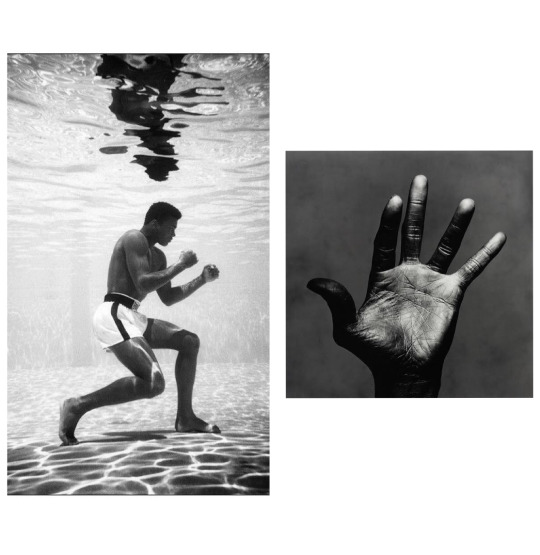

Flip Schulke - Muhammad Ali Training Underwater (1961)

369 notes

·

View notes

Text

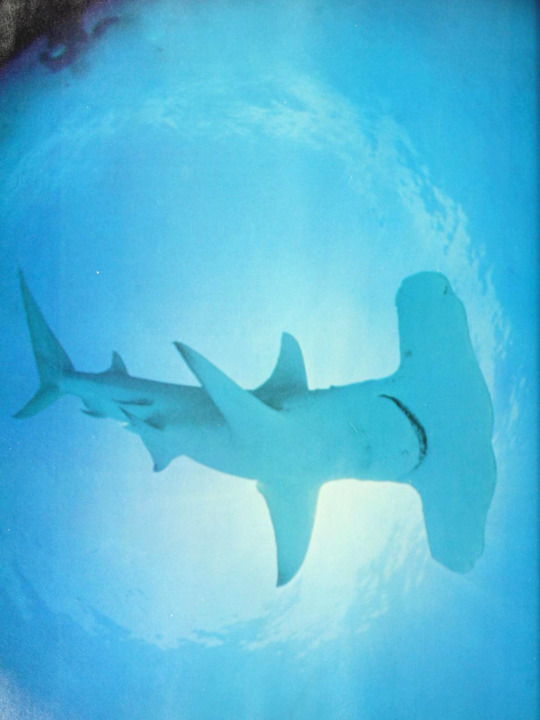

Hammerhead shark

By: Flip Schulke

From: The Fascinating Secrets of Oceans & Islands

1972

#hammerhead shark#shark#cartilaginous fish#fish#1972#1970s#Flip Schulke#The Fascinating Secrets of Oceans & Islands

128 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flip Schulke. Ali Underwater. 1961

#BW#Black and White#Preto e Branco#Noir et Blanc#黒と白#Schwarzweiß#retro#vintage#Flip Schulke#Muhammad Ali#underwater#boxer#sports#portrait#retrato#Celebs#celebridade#ポートレート#肖像#Porträt#Berühmtheit#有名人#名士#célébrité#1961#1960s#60s

649 notes

·

View notes

Text

source: bishopsbox

A group of teenage girls scream obscenities at Black students entering their high school in Montgomery, Alabama,September 10, 1963, by Flip Schulke.

Un grupo de chicas adolescentes gritan obscenidades a los estudiantes negros que entran en su instituto en Montgomery, Alabama, 10 de septiembre de 1963, por Flip Schulke.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rush, Permanent Waves Cover Artwork.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martin Luther King Jr. playing with his children Dexter King, Yolanda King and Bernice King in their backyard in Atlanta on November 8, 1964.

Photos by Flip Schulke

#dr king#mlk#martin luther king jr#1964#yolanda king#dexter king#bernice king#1960s#mlk jr#civil rights#black history

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Developing Local Cultus: A Companion Library

In preparation for the revamping of my Local Cultus series over on wordpress, I have begun to gather this small reference library for anyone who may be interested. Containing mostly works which inspired me to set out on the path of developing a localized religious practice, as well as some of my research materials. For those interested in the series, and the topic which it covers, I absolutely recommend giving these titles a flip through.

The first of this series, an introduction and mapping out of what is to come, will be up on the Barn Cultus website by the end of July.

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Indispensable knowledge of ecological relationships as written by an indigenous woman and professor of environmental biology.

The Green Mysteries by Daniel Schulke

An encyclopedia of the spiritual, magical, and folkloric qualities of plants. Written by the Magister of the Sabbatic tradition.

The Golden Bough by James George Frazer

Frazer tracks the role of religion and magic up until the modern day, introducing along the way some of the key ideas behind my style of cultus developing (such as re-enchantment). This book is always on my reference shelf, close at hand, and while the anthropology is at times laughably outdated, it is a beautiful read with some interesting groundwork.

Viridarium Umbris by Daniel Schulke

I'd be remiss to not include this in my list. Another Schulke work and a comprehensive grimoire of verdant magics. I personally view this book as overhyped, though a should-read, perhaps not a must.

Demons & Spirits of the Land: Ancestral Lore and Practices

A foundational text of folkloric land spirits and the operations used by Pre-Modern Europe to interact with them.

Roman Cult Images: The Lives and Worship of Idols from the Iron Age to Late Antiquity

In my own eyes, the finding of localized images. Images references the faces, attributes, and fauna of the region in which each divinity of the cultus is depicted. The crafting of cult images, in the forms of eikons and idols, is another aspect of this.

Idolatry Restor'd by Daniel Schulke

Schulke speaks to the ensouled fetish, which connects greatly to the idea of the Living Statue and the cultic image. More of a sorcerous read, but worth it nontheless.

We Are In The Middle of Forever: Indigenous Voices of Turtle Island on the Changing Earth

I hold the strong conviction that those of us in America who find our bloodlines here through the powers of colonialism absolutely must be listening to indigenous wisdom- full stop. Publications like this one are a huge boon to the mending of the rift between the descendants of colonialism and the land which they inhabit. I think this becomes doubly important to those practices land-based religions.

The Sacred and the Profane by Mircea Eliade

I come with the bias of studying the anthropology of religion full time. This book has in many ways aided in bridging the gap between my academic studies and the building of my theologies, and is a profound read by an author with a storied collection of publications within the field.

Mystai: Dancing out the Mysteries of Dionysus

An interesting look into the mystery cult of Dionysus during late antiquity. Mystery cults often operated regionally and with localized aspects to their mysteries.

Eleusinian Mysteries and Rites by Dudley Wright

All literature on the Eleusinian mysteries is a boon- this is my recommendation. Following the ritual life of the local agriculture cult which has gone down in history as one of the largest surviving cults into the Christianization of Greece.

Walking the Worlds: Building Regional Cultus

Less of an academic read than the others on this list, but one I found equally as inspiring. The articles speak to diaspora and tensions of modern polytheism, and I think without some kind of academic pre-knowledge of these topics the articles themselves would fall a little flat, but a worthy read for the genuine pursuant.

Mystery Cults in the Greek and Roman World by the MET

Kongo in Haiti: A New Approach to Religious Syncretism

by Luc de Heusch

This article explores religious syncretism through the lens of Vodou, an African traditional religion known for its syncretic relationship with Christianity here in the US and Haiti. De Heusch explores a little bit of the roots in West Africa, and how the religion operates in both syncretic and nonsyncretic ways across the African diaspora.

Why Cecropian Minerva?: Hellenic Syncretism as System

by Luther H. Martin

This article explores syncretism in a western context, from the other side of the isle. This is not syncretism brought on by oppression and colonialism, instead highlighting syncretism theologically proposed by the oppressors, a favorite of the Romans. Martin explores the theology of this, the politics of this, and offers interesting analysis of the historical evidence.

Epithets in the Orphic Hymns by W. K. C. Guthrie

There's powers in names. You know it, I know it, Guthrie certainly knows it. Behind that power is meaning. While Guthrie does not particularly touch on regionalized epithets, I still find this to a be a great read to get one thinking about cult specific poetic titles.

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flip Schulke photographed the unusual image of the diver swimming close to the head of Namu, an orca. Puget Sound, 1966. "Known by divers internationally as the Pioneer of the Pioneers, Hans Hass started his diving career in the 1930s. He was the first free-swimming film maker to film and photograph sharks, manta rays, and whales in their natural environment. A prolific writer, Hass had published six books on diving by 1950. He left the underwater world in 1960 and was largely forgotten by the diving industry..." From "Die Welt unter Wasser der abenteuerl Vorstoss d. Menschen ins Wasser" by Hans Hass, 1973. https://www.instagram.com/p/CejbHoztwtl/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

149 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flip Schulke: Muhammad Ali Training Underwater (1961).

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

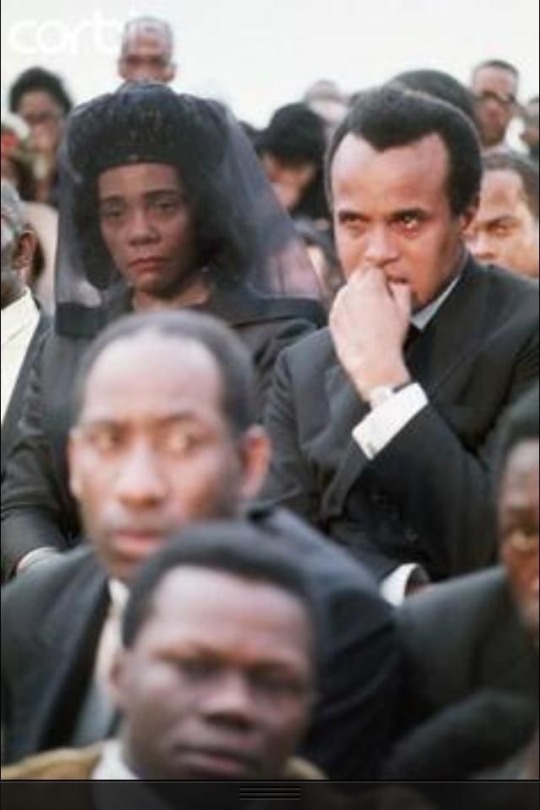

flip schulke/corbis - harry belafonte & coretta scott king at dr king’s funeral, atlanta, georgia, 1968

#martin luther king jr#1968#funerals#coretta scott king#harry belafonte#i have a dream#civil rights#america

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flip Schulke - Cathy Shirriff wearing a dress from the prop shop, 1972

0 notes

Text

Works Cited

Flip Schulke Archives, and CORBIS. Teenage Boys Against

Integration. Gettyimages, Gettyimages, https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/news-photo/crowd-of-teenage-boys-protest-against-school-integration-news-photo/541222540. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

Green sign saying “The Truth Just Ahead.” Walkamileproject, The

Walk a Mile Project, https://walkamileproject.com/discover-the-truth/. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

Mosely, John W. Philadelphia Transit Company protest supporting

minority transit drivers at Reyburn Plaza in Center City Philadelphia on November 8, 1943. Hiddencityphila, HIDDEN CITY, https://hiddencityphila.org/2016/09/a-million-faces-exhibition-celebrates-the-photography-of-john-mosley/. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

Proven Innocent. Fox Pivot GIF. Giphy, Giphy,

https://giphy.com/gifs/InnocentOnFOX-fox-proven-innocent-innocentonfox-fxwrhUeEyFkAKgwxqr. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

Riotgamesmusic. Rock Climbing Rise Song GIF. Tenor, Tenor,

https://tenor.com/en-CA/view/rock-climbing-rise-song-going-up-hiking-climbing-the-mountain-gif-25792523. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

Scherman, Rowland. Leaders marching from the Washington

Monument to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, August 23, 1963. . 13 Jan. 2017. Adl, ADL, https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounder/civil-rights-movement. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

Underwood Archives. Author Langston Hughes. Gettyimages,

Gettyimages, https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/news-photo/portrait-of-poet-author-playwright-and-harlem-renaissance-news-photo/538349071. Accessed 2 Oct. 2023.

Vechten, Carl Van, and Cropped by Beyond My Ken.

LangstonHughes crop. 5 Aug. 2010. Wikimedia, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LangstonHughes_crop.jpg. Accessed 2 Oct. 2023.

Wind and Fly LTD. Martin Luther King, Jr. Azquotes.com, AZQuotes,

https://www.azquotes.com/quote/877272. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

0 notes

Text

The Struggle For Civil Rights in Mississippi

An Encounter with Dr, Martin Luther King, Jr., During a Summer of Pressure.

— Letter from Jackson | August 29, 1964 Issue | By Calvin Trillin | August 21, 1964

— Monday January 16th, 2023

Photograph by Flip Schulke/Getty Images

Published in the print edition of the August 29, 1964, issue.

To people who happen to be admirers of Spanish Civil War literature, Jackson as the headquarters of the Mississippi Summer Project is likely to conjure up visions of Madrid as the capital of the Spanish Loyalists. Physically, Jackson could hardly look less like Madrid, but the Summer Project—a statewide program of voter registration and other civil-rights activities which is being carried out by some six hundred volunteers and some one hundred paid workers—is so thoroughly caught up in a tangle of frenetic planning and propagandizing that a reader of George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway half expects to come across military strategists mapping out campaigns against mountain villages or to see clusters of ideologists arguing and plotting in small, dark bars, their conversations occasionally interrupted by a stray bomb. One difference, of course, is that the Council of Federated Organizations, or cofo—the amalgam of civil-rights groups that runs the Summer Project—does not actually control even the part of Jackson where it is permitted to exist, and there are constant reminders of who does. A number of editorialists and columnists on the Jackson daily newspapers are not merely segregationists but segregationists of the type who are inclined to indicate their position by referring to Martin Luther King as “the Rev. Dr. Extremist Agitator Martin Luther King, Jr.,” or by suggesting that President Johnson’s theme song should be “The High Yellow Rose of Texas,” or by telling cannibal jokes; the community bulletin board of a local radio station occasionally includes among reports of rummage sales and church suppers the announcement that Americans for the Preservation of the White Race will hold its weekly meeting that evening and “all interested white people are invited to attend;” the chatty gray-haired lady in charge of a local bookstore, whose inventory appears to begin with the writings of the John Birch Society and move to the right, is available for political arguments with the civil-rights workers she refers to amiably as “those cofo things;” one can telephone Dial for Truth, a recorded announcement by the Jackson Citizens Council of the evils that race-mixing has brought upon the world during the previous week; and the Mississippi Numismatic Exchange, Inc., has a sign in its window reading, “Kennedy Half Dollars 25¢. That’s All We Think They’re Worth!” (The sign says in smaller letters that the case that goes along with one costs fifty cents.)

Still, Jackson, which prides itself on maintaining law and order, has been relatively careful about protecting civil-rights workers, and there has not been enough civil-rights action within the city limits to provide what cofo people tend to call a confrontation; all in all, the city is more of a communications-and-planning center than a scene of battle. At the cofo headquarters, a storefront office on Lynch Street, in the Negro business district, efficient white girls in cotton print dresses decorate the walls daily with fresh “incident reports” listing arrests or beatings of cofo workers in other parts of the state, but whenever the stray bomb lands—as on the second day of my visit, when two workers were beaten, though not seriously, just a few blocks from the cofo office—the first reaction is that somebody must have broken a truce or wandered into a demilitarized zone by mistake. At the office, cofo workers in overalls and work shirts who have come into Jackson on errands from small towns in the Delta stroll in and out, and members of the office staff shuttle back and forth incessantly between a row of typewriters and a row of telephones. On Farish Street, in another part of the Negro business district, two groups of lawyers use offices across the street from one another—each on the top floor of a drab two-story building—to deal with the litigation brought on by the constant civil-rights arrests. In an office nearby, the National Council of Churches, which has provided ministers, lawyers, and the training facilities for the Summer Project, regularly holds orientation sessions for new arrivals, and a group of respectable-looking clergymen regularly watch quietly as a cofo worker demonstrates how to protect one’s kidneys when knocked down. (“Is it considered permissible to get in a punch or two and then run?” a young minister asked the day I was there. “How good a runner are you?” the cofo demonstrator asked in reply.) Over in the white business district, workmen are installing an interior staircase in the expanded F.B.I. office, which now occupies one floor and part of another of the new First Federal Savings & Loan Building, and is still in the unpackaging stage, with crates on the floor and pictures of J. Edgar Hoover leaning against the wall. At the state Capitol, a few blocks to the north, where a statue of Governor (and Senator) Theodore Bilbo, the late racist, dominates the ground floor, and vividly tinted portraits of Mississippi’s two Miss Americas are enshrined in the rotunda, investigators for the State Sovereignty Commission, the agency charged with preserving segregation, go through Negro newspapers, civil-rights literature, and the Worker in order to keep track of which Left Wingers are where. All in all, there are so many visitors in town that it is practically impossible to rent a car, and the provision of restaurant and hotel accommodations for the visitors has become a minor industry. Under these circumstances, a conversation about the Catalan separatists or the anarchists of the P.O.U.M. might not sound out of place, but instead the visitors talk about S.N.C.C. (called “Snick” and standing for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), or the National Council (of Churches), or the L.C.D.C. (Lawyers Constitutional Defense Committee), or the (National) Lawyers Guild, or the A.P.W.R. (Americans for the Preservation of the White Race), or the Citizens Council, or the Klan.

Jackson has never stood apart from the rest of Mississippi the way Atlanta has stood apart from Georgia, say, or New Orleans from Louisiana. Traditionally, it has merely been a larger town than the other towns in the state, and not until after the Second World War was it very much larger. In 1940, it had a population of sixty-two thousand. Now, however, with a population of a hundred and fifty thousand and with ambitions for further expansion, Jackson is the logical place to expect to see any significant indications of moderation on the race issue in Mississippi—not because the capital has ever been particularly liberal compared to the rest of the state but simply because it now has the most to lose through the chaos that total defiance of federal desegregation provisions could bring. Such indications appeared recently when it began to look as though the city might comply peacefully with a federal-court order that schools start desegregating this fall, and when the board of directors of the Chamber of Commerce made a surprise statement advising businessmen to comply with the public-accommodations section of the new civil-rights law. After the fact, it is not difficult to find a number of good reasons for the Chamber’s statement. This summer marks the first time Jackson businessmen have ever been faced with anything approaching the power of a federal law. Previously, it was possible to see the conflict as one between the state and a group of Negroes; the civil-rights law expanded it, potentially, into one between each individual businessman and the federal government. (There is a theory in Jackson that Mississippi fell victim to its own propaganda; that is, there was so much publicity about how a civil-rights law could result in a decent American businessman’s being hauled off to court or to jail by the Federal Dictator for choosing his own customers that the local businessmen were psychologically prepared for an early surrender.) It is said that business in Jackson was damaged somewhat by the demonstrations and boycotts of last summer, and that businessmen—particularly those directly affected by the law—were happy to be able to make the inevitable transition peacefully by blaming it on the federal government, especially since many of them apparently believed (erroneously) that all those cofo things in town were likely to stage an impressive demonstration for all the F.B.I. people in town on the Fourth of July. Although the national headquarters of the Citizens Councils of America is in Jackson, the local Council has never embraced all the important businessmen, as it does in some smaller Mississippi towns, and the suggestion has been made that its point of view seemed to be dominant only because a segregation issue of vital importance to business had not come up. According to one person who was close to those who drafted the Chamber’s statement, “Folks didn’t realize the number of people here who are able to recognize the inevitable when it arrives.” Those people, who had remained silent while the inevitable was approaching, acted with a suddenness that caught the Citizens Council element by surprise. There is reason to believe that their action will result in preserving almost complete segregation while avoiding public disturbance—since the facilities, if made available without challenge, are not likely to be used by a great many Jackson Negroes—but in the past even that argument was not enough to justify a public statement in favor of desegregation, so while people familiar with Jackson are able to explain why such a statement was wise, they admit surprise that it was issued. The Chamber’s statement, according to one member of its board, was “a calculated risk,” and once it had succeeded—and of the fourteen hundred firms affiliated with the Chamber only four resigned—there was bound to be less pressure against those who were willing to recognize the possibility of change in Mississippi.

A few days after the Chamber advised compliance, the mayor of Jackson supported its stand, and a week or so after that, when Mississippians for Public Education, a group composed mainly of housewives, announced its existence and its intention of opposing any scheme that might damage the public schools—such as the establishment of private segregated schools supported by state tuition grants—its members, to their amazement, met with practically no abuse. Four days after the group’s announcement, its president had received only two letters criticizing her position (one of them asked, among other things, if she realized that “academic standards have fell in any place that has had integration”), and none of the officers in Jackson had received a single unsigned hate letter or late night phone call.

Nevertheless, moderation is far from being the predominant viewpoint in Jackson. The housewives have not yet received any public support from businessmen—in other Southern cities, civic leaders have eventually been willing to support public education after the housewives have tested the opposition for a while—and it is believed that the statement in favor of compliance would not have been passed by the Chamber of Commerce if the Citizens Council element had been given time to marshal its forces. Much of Jackson’s inclination toward compliance can be explained not by any decrease in segregationist feeling in Jackson but by an increase in pressure from the outside. Desegregating restaurants in compliance with a federal law is quite a different thing from desegregating them through negotiations with local Negroes, and now that ten years have passed since the original Supreme Court decision, federal courts have eliminated practically every alternative to obeying a school-desegregation order. All the fund cutoffs, school closings, and various postures for standing in the schoolhouse door have even lost most of their force as ritual. It is clear to most people in Jackson that the public schools will be desegregated no matter what opposition is put up—something that was apparently not clear to many of them before the University of Mississippi desegregation—and about all that the last session of the legislature could think of to do about it was to provide tuition grants for those who wanted to attend private segregated schools. The story is often told now in Jackson of a University of Mississippi trustee who departed for the hearing before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans with his bags packed and his farewells said in preparation for going to jail rather than admit James Meredith to the University. According to the story, the trustee—after listening to the judge explain that if the trustees failed to admit Meredith they would be jailed for contempt and new trustees would be appointed to admit him—turned to the state’s lawyer and said, “You mean I’ll be in jail in New Orleans and that nigger will be in school at Ole Miss?” When the lawyer confirmed that interpretation, the trustee decided that no purpose would be served by his going to jail.

The immediate effect on the rest of the state of the Jackson Chamber’s statement is expected to be limited. Although there has been some compliance in the larger cities, no other Chamber of Commerce has made a statement on the civil-rights law, and it will be a long time before a Negro eating in a “white” restaurant is a common enough sight to shake the conviction of those who prefer to believe that nothing has changed. School integration is considered the important test. Many people have expressed cautious optimism about school desegregation’s proceeding peacefully in Jackson and in Biloxi—which is on the Gulf Coast, an area traditionally more flexible on the race issue than most of the rest of the state—although there are few predictions about rural Leake County, which is also under a school desegregation order. The important long-range effect of both the Chamber’s statement and the appearance of Mississippians for Public Education is that, in the words of a Jackson lawyer, “some crack has been made in that wall of Never.”

The wall of Never was built on the proposition that in Mississippi complete segregation could be maintained without violence by means of rigid control—some say police-state control—within the state and a united front against outside pressure. As the outside pressure becomes greater and more firmly supported by law, there is often no way to oppose it except by lawlessness. Many of this summer’s incidents—the burning of Negro churches unconnected with civil-rights activity, for instance—are typical not of the systematic intimidation associated with the Citizens Councils but of the irrational violence indulged in by terrorist groups of a sort that cannot be controlled by strategists in Jackson. Organizations such as the Klan and the A.P.W.R. hardly existed in Mississippi a year or two ago, and although the administration of Governor Paul Johnson has not condemned them out of hand, it has discouraged people from joining them. Governor Johnson did advise businessmen not to comply with the civil-rights act until it had been tested in the courts, but he is still considered quite a bit less extreme than former Governor Ross Barnett, and there are certainly indications that the state has tried to avoid trouble that might bring federal intervention on a large scale. When Martin Luther King visited the state recently in support of the Freedom Democratic Party (a predominantly Negro political party that is attempting to unseat the regular Mississippi delegation at the Democratic Convention, on the theory that the regular party cannot represent people it prevents from voting), he was carefully, if unobtrusively, protected by the state as well as by the F.B.I. Outright violence against cofo workers has been officially discouraged, and despite the murder of the three civil-rights workers in Philadelphia during the Summer Project’s first week, there has been less of it than many people expected. Those in control of the state would much prefer to deal with cofo by calling its workers Communists and beatniks and by arresting them for some crime such as distributing leaflets.

happened to fly from Atlanta to Jackson on the same plane as Martin Luther King, who was about to begin his tour of Mississippi with some speeches and meetings in Greenwood. He was accompanied by four of his aides in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—Andrew Young, C. T. Vivian, Bernard Lee, and Dorothy Cotton—and except that all of them are Negroes and that the men were wearing buttons in their lapels that said, “S.C.L.C. Freedom Now,” the group might have been thought to consist of a corporation executive off to make a sales-conference speech accompanied by efficient, neatly dressed young assistants brought along to handle arrangements and take care of the paperwork. As the plane left Atlanta, Young began going through a number of file folders, making notes on a legal-sized yellow pad and occasionally passing them up to King, who paused in his reading of the Times and the news magazines now and then to consult with Young or Mrs. Cotton. Lee opened “The Souls of Black Folk,” by W. E. B. DuBois, and Mrs. Cotton brought out a copy of “Southern Politics,” by V. O. Key, which she read when she wasn’t talking with King. Across the aisle from King, there happened to be sitting a stocky, nice-looking young white man with a short haircut and wearing Ivy League clothes. He looked as if he might have been a responsible member of a highly regarded college fraternity six or eight years ago and was now an equally responsible member of the Junior Chamber of Commerce of a Southern city that prided itself on its progress. About halfway between Atlanta and Montgomery, the plane’s first stop, he leaned across the aisle and politely said to King, in a thick drawl, “Excuse me. I heard them calling you Dr. King. Are you Martin Luther King?”

“Yes, I am,” said King, just as politely.

“I wonder if I could ask you two questions,” the young man said, and Young, Vivian, and Lee, all of whom were sitting behind King, leaned forward to hear the conversation. “I happen to be a Southerner, but I also happen to consider myself a Christian. I wonder, do you feel you’re teaching Christian love?”

“Yes, that’s my basic approach,” King said. “I think love is the most durable element in the world, and my whole approach is based on that.”

“Do you think the people you preach to have a feeling of love?” the young man asked.

“Well, I’m not talking about weak love,” King explained. “I’m talking about love with justice. Weak love can be sentimental and empty. I’m talking about the love that is strong, so that you love your fellow-men enough to lead them to justice.”

“Do you think that’s the same love Jesus taught?” the young man asked.

“Yes, I do.”

“Even though you incite one man against another?”

“You have to remember that Christ was crucified by people who were against him,” said King, still in a polite, careful tone. “Do you think there’s love in the South now? Do you think white people in the South love Negroes?”

“I anticipated that,” said the young man. “There hasn’t always been love. I admit we’ve made some mistakes.”

“Uh-huh. Well, let me tell you some of the things that have happened to us. We were slaves for two hundred and fifty years. We endured one hundred years of segregation. We have been brutalized and lynched. Can’t you understand that the Negro is bound to have some resentment? But I preach that despite this resentment we should organize militantly but non-violently. If we organize non-violently, we can show the injustice. I don’t think you’d be talking to me now if we hadn’t had some success in making people face the issue.”

“I happen to be a Christian,” the young man repeated.

“Do you think segregation is Christian?” asked King.

“I was anticipating that,” the young man said. “I don’t have any flat answer. I’m questioning your methods as causing more harm than good.”

“Uh-huh. Well, what do you suggest we need?” King was able to say “Uh-huh” in a way that implied he had registered a remark for what it was worth and decided not to bring up its more obvious weaknesses, but he and the young man did seem genuinely interested in each other’s views.

“I think we need respect and good will,” said the young man.

“How do you propose to get that?” King asked.

The young man hesitated for a moment and then said, “I don’t know. I just don’t agree that it does any good to incite people. I know there’s resentment, and you’re able to capitalize on this resentment and create friction and incite discord. And you know this.”

“I don’t think we’re inciting discord but exposing discord,” King said.

“Well, let me ask you this,” said the young man. “Are you concerned that certain people—well, let’s come out with political labels—that this plays into the hands of the Communists?”

“I think segregation and discrimination play into the hands of the Communists much more than the efforts to end them,” said King.

“But it’s certainly been playing into the Communists’ hands since you and the others—as you put it—started exposing what was there. There’s certainly more attention given to it.”

“Don’t you think that if we don’t solve this the Communists will have more to gain?”

“I think much more progress was made between the two races before the last few years, when you and other people started inciting trouble between the two races.”

“What is this progress?” asked King. “Where was the lunch-counter desegregation? Where was the civil-rights law?”

“In good relations,” the young man answered.

“Good white relations,” interrupted Vivian, who apparently felt unable to keep out of the argument any longer.

“Well, I just wanted to ask those questions,” said the young man. He seemed ready to end the discussion.

“Uh-huh,” said King. “Well, I’d like to be loved by everyone, but we can’t always wait for love. Maybe you ought to read my writings. I’ve done quite a bit of writing on non-violence.”

“Well, I think you are causing violence,” the young man said.

“Would you condemn the robbed man for possessing the money to be robbed?” asked King. “Would you condemn Christ for having a commitment to truth that drove men to crucify him? Would you condemn Socrates for having the views that forced the hemlock on him? Society must condemn the robber, not the man he robs.”

“I don’t want to discuss our philosophical differences,” said the young man. “I just wanted to ask you those questions.”

“Uh-huh. Well, I’m sorry you don’t think I’m a Christian.”

“I didn’t say that.”

“Well, I’m sorry that you don’t think that what I preach is Christian, and I’m sorry you don’t think segregation is un-Christian.”

King turned back to his paper for a few moments, as if the conversation had ended—without progress but with no animosity—and then he looked up and said to the young man, “What do you think of the new civil-rights law? Do you think that’s a good law?”

“Well, I haven’t read it, but I think parts of it just carry on the trend toward federal dictatorship.”

“You sound like a good Goldwaterite,” said King, with a slight smile. “Are you going to vote for Goldwater?”

“Yes, I expect I will,” the young man said.

“It’s too bad you’re going to back a loser, because I’m afraid we’re going to hand him a decisive defeat in November.” King’s tone was light; he might have been joking with a long-time neighbor who had always been a member of the opposing political party.

“I’ve voted for losers before,” said the young man.

King turned back to his reading, and Vivian said, “What do you mean by federal dictatorship?”

The white man didn’t seem anxious to take on a fresh adversary, but he replied, “I think everything should be done at the lowest level of government.”

“How about all the federal hospitals? The roads?” said Vivian. “You say you want the federal government to stay out of everything unless it has to do it. That’s why you have those hospitals and roads in Georgia, because Georgia was too poor to pay for them. Do you know how much more Mississippi takes from the federal government per person than it puts in? You didn’t start talking about federal dictatorship until it came to race—”

“Are you asking me a question or making a speech?” said the young man.

“Both,” Vivian said.

King looked up from his paper and smiled across at the young man. “We’re all preachers, you see,” he explained, and then turned to discuss something with Mrs. Cotton as the young man was making a point to Vivian.

“You must be talking about Toynbee’s book,” said Vivian, and he launched into a rapid-fire series of questions about Toynbee’s theories on race.

“There’s no need to debate this,” the young man said finally, and he began to look out the window. At Montgomery, he walked off the plane.

“What do you think of that?” King asked, shaking his head, as the white man left. “Such a young man, too. Those are the people who are rallying to Goldwater. You can’t get to him. His mind has been cold so long there’s nothing that can get to him.”

The young man returned to the plane before it left Montgomery, but, with a quick, embarrassed smile, he walked past King and the others and settled in a rear seat.

Lunch was served between Montgomery and Meridian, and afterward Lee went to sleep and Young crossed the aisle to talk with Vivian about arrangements for that night. “I called the Justice Department today, and they said they think we should go back to Jackson after the meeting,” he said.

“I don’t like to have Dr. King on the road at night,” Vivian replied.

“Apparently, Greenwood is the kind of place now where a mob might form,” said Young. “They came right into the Negro neighborhood a few months ago to get the kids at the S.N.C.C. office.”

“I never know if the Justice Department knows something it’s not telling us,” said Vivian. “But I hate to be on the road.”

“Even with a state-patrol escort?”

“That state patrol isn’t a patrol,” Vivian said.

“I hear they were pretty good with the congressmen who went down there,” said Young.

“Well, maybe so.”

“Well, let’s see what the mood is when we get there,” Young said in conclusion. He walked across the aisle, lowered the back of his seat, and soon went to sleep. In front of him, King was engrossed in a news magazine.

A number of the white Mississippians who do not consider cofo workers Communists or beatniks—and they are clearly in the minority—believe that the presence of people who look like Communists or beatniks is enough to alarm the residents of a small, churchbound, isolated Mississippi town, even if it is not the sort of town whose sheriff ordinarily shows his alarm by beating up strangers. Mississippians have given a good deal of attention to the appearance of the cofo workers—who favor overalls, old shirts, and, in some cases, beards—and particularly to the appearance of the white volunteers. Although it is true that the people attracted to the Summer Project include some who would qualify as beatniks in Mississippi, where the word is defined broadly, the great majority of the volunteers are white college students who tend to dress the way their hosts dress. As it happens, cofo is, for all practical purposes, a project of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (the participation of the other national civil-rights organizations involved—the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—ranges from limited to nominal), so the style-setters are the staff members of S.N.C.C., which may once have been a coat-and-tie organization but is so no longer. With their overalls, S.N.C.C. field workers often wear the flat-topped, broad-brimmed straw hats that are popular among rural Negroes in Mississippi; James Forman, the Negro executive secretary of S.N.C.C., who has set up headquarters in Greenwood for the summer, is usually seen in blue jeans; and the founder and director of the Summer Project, a twenty-nine-year-old Negro S.N.C.C. worker named Robert Moses, who has been in Mississippi for three years, wears work pants and a T-shirt even when he is in New York trying to raise money. What has been obscured by all the talk about the volunteers’ being beatniks is that the dress of the cofo workers is really quite significant as an indication of how deeply the protest movement has changed in the few years since Negro students—some of them the same ones who are now involved in cofo—sat at dingy dime-store lunch counters dressed in freshly pressed three-button suits. Moses has remarked, “This movement is pointed in a different direction—not toward the downtown white but toward the rural Negro, not toward acceptance by the white community but toward the organization of political and other kinds of expression in the Negro community, or really toward the organization of a Negro society. And the dress is a symbol of that.”

“Basically, we’re dealing with poor people, and these are the people we identify with,” Forman has explained. “It even affects our salary scale. One reason it’s so low is just lack of money, but another reason is that we think you can’t come out from a nice hotel every day to work with these people and then go back at night. Besides, in Mississippi, as a practical matter, you have to look like a rural Negro in order to get to talk to a rural Negro. And then we have to move a lot, and there’s no use wearing a coat and tie if you’re likely to end up sleeping on the floor. Another thing that’s operating here, too, consciously or unconsciously, is: Why should we have to comb our hair and put on a coat and tie to get what are basically our rights? The student movement was positive, and without it we couldn’t have had this, but it was also defensive—to show people we were clean. This is a different game. Also, there’s a certain mystique about the dress, a certain morale factor. Maybe we’ve overdone it; it’s almost a uniform now. A lot of this summer’s volunteers went out and bought blue denim shirts and overalls. They thought they had to have them.”

The attitude toward clothing has its counterpart in other phases of the Summer Project. In 1960, the Atlanta sit-in movement—which, admittedly, was even more middle-class than the movements in most cities—avoided association with core, partly because of a belief that it was too far left politically. cofo, against the advice of many of its Northern-liberal supporters, and after a good deal of internal debate, decided to accept help from the National Lawyers Guild—which is sometimes accused of being pro-Communist—because its leaders believed that the need for competent lawyers was desperate enough to make the loss of Northern-liberal support worth risking in order to get them. (It was partly in response that the Northern liberals sent lawyers of their own, whose help cofo was also happy to accept.) The Freedom Houses that cofo has established in a number of communities throughout the state to lodge its workers, and the other accommodations it has arranged in private homes, are usually interracial and unchaperoned, and the cofo answer to suggestions that this might be bad strategy is that Mississippi does not have a renters’ market in Freedom Houses and it is more important to send as many workers as possible to whatever houses are available than to worry about antagonizing local whites, who are likely to be antagonistic anyway. “When I first came down here, I walked down the street to the courthouse with two local Negroes, and some people tried to beat my brains out,” Moses says. “If you get the most extreme reaction to the most innocent move, you might as well do what you want. This isn’t an army. We can’t call up people in the field one day and say now the Communist issue will be imposed, and call up another day and say now the dress-up-and-clean-up issue will be imposed, or now the white-girl issue will be imposed. These people are risking their lives. They have to make their own decisions, and they tend to emphasize their involvement rather than disguise it. We really look upon all these things—the political arguments of the thirties and the forties, the impressions of the whites—as impositions from the outside.”

At the heart of S.N.C.C.’s lack of concern with the impressions that its people make is the fact that its interest is not in having Negroes accepted into Mississippi society but in changing Mississippi society; its approach is—in the pure sense of the word, rather than in the sense more common here this summer—radical. The decision to begin with the most impenetrable state, by concentrating on Mississippi, was itself radical. The S.N.C.C. approach since 1961—when the organization, then almost dormant, decided to hire full-time field workers rather than merely to coördinate the activities of college students—has been split between direct action and voter registration, sometimes combined to produce what Forman calls “community mobilization.” S.N.C.C. was convinced from the outset that Mississippi had to be cracked, but soon discovered that direct action, which ran into a stone wall of high bails and severe jail sentences, was not the right method of cracking it. (Today, Jackson businessmen need have no fear of cofo’s demonstrating in restaurants. As a matter of strategy, S.N.C.C. leaders prefer to keep the Mississippi conflict based on the most fundamental Constitutional right—the right to vote—and as a matter of philosophy they do not consider restaurant integration particularly relevant in Mississippi; in fact, they do not even patronize the restaurants that have desegregated under the civil-rights law. “Sure we could go to the desegregated restaurants,” Moses says. “But could the Jackson Negro who might get fired for it go there? And how about the Negro who makes fifteen dollars a week?”) It was also in 1961 that Moses—an intense, soft-spoken, and self-effacing young man, who graduated from Hamilton College, got a Master’s degree in philosophy from Harvard, and had been teaching mathematics at the Horace Mann School in New York—went South to see what he could do to help. Working as a S.N.C.C. field secretary, Moses moved from one city to the next until he found a place where there was no established Negro leadership to resent him as an outsider; that turned out to be rural southwest Mississippi. At that time, some S.N.C.C. leaders believed that the Justice Department was advising concentration on voter registration to divert civil-rights groups from the more explosive field of direct action, but Moses discovered that, as he later said, “in Mississippi voter registration was itself an act of confrontation,” and one that could eventually result in the most fundamental changes.

So far, in Mississippi, the confrontation has continued to be more significant than the registration. The simplest way to misunderstand cofo is to think of it as a project whose primary aim is to achieve a gradual increase in the Negro vote. Because of Mississippi’s complicated literacy tests, the fear and apathy of its Negroes, and the range of intimidation available to its whites, cofo, at its current pace, will never register enough Negroes in the state to make any difference. In his speeches throughout Mississippi, Martin Luther King, in calling for federally appointed marshals to register voters in some counties, pointed out that for all the extraordinary efforts of the past three years, even at slightly better than the present rate, it would take a hundred and thirty-five years to register half the state’s eligible Negro voters. The Voter Education Project—a coördinated voter-registration effort supported by foundation grants and administered by the respected Southern Regional Council—supported S.N.C.C.’s Mississippi registration drive for two years and then withdrew, on the ground that an organization committed to registering Negro voters would never be able to justify the expenditure of any money in Mississippi. The organization’s second annual report declared, “V.E.P. has only been able to add 3,871 voters to the rolls in Mississippi during the past two years, a figure lower than the results from a single small city like Brunswick or Decatur, Georgia, or Winston-Salem, North Carolina. . . . We only hope that the situation improves before V.E.P. goes out of existence, but it will not change appreciably without massive federal action.” Not only is it difficult to get Negroes registered in Mississippi but it is almost impossible even to find out how many Negroes have been registered; information is so skimpy that the figure usually quoted for Negro registration—twenty-eight thousand, which many people believe is an overestimate—has as its original source a 1955 University of Mississippi Master’s thesis.

Moses is interested in registering Negroes, and still more interested in breaking through their fear enough to convince them that they should try to register. Most of all, though, having found that in almost any town a small group of Negroes could be built around voting, he sees voting registration as a means of organizing a society. Arguing that “you can’t have a political revolution in a vacuum,” he maintains that without organizing themselves and creating leaders of their own Negroes in Mississippi will not be able to use the vote effectively when it comes, and will also never be able to help themselves socially and economically. Almost everything that cofo does has two or three purposes, in addition to the basic idea that there is value in organizing Mississippi Negroes and “shaking up the state” no matter what the purpose. The Freedom Schools set up by cofo in some thirty Mississippi communities may teach Negro teen-agers enough civics and English to help them pass the voting test someday, but they also provide a means of improving the teen-agers’ pitiful education, of permitting them, for the first time, some freedom of inquiry, and of developing leaders who are not afraid to lead. (A large percentage of S.N.C.C.’s Mississippi staff is composed of young people who have been recruited over the past three years by Moses and others during the organizing of Mississippi communities.) The Freedom Democratic Party is partly a means of demonstrating how many Negroes would vote if they were permitted to, partly a means of inspiring Negroes to vote, partly a means of teaching them the rudiments of political structure, and, inevitably, partly a means of just organizing. This constant organizing of lower-class Negroes means that the civil-rights movement, which until the past two or three years was largely a middle-class movement in the South, is now much more deeply concerned with social and economic problems. cofo has established community centers that are basically social-work centers, and it has a branch, called Federal Programs, that investigates discrimination in the distribution of federal funds and also tries to show Negroes how to get the federal aid that they are entitled to. Among S.N.C.C. workers, “bourgeois” is widely used as a term of insult.

The concern with social and economic problems reflects the views of Moses, who describes himself as merely an organizer and seems to have no interest in being a “civil-rights leader.” Many of those who work with him consider him, quite simply, a saint. “You should hear him talk to some of these people,” one of them told me. “I heard him in Ruleville once talking to a church full of farm laborers. He said, ‘This spring, you’re going to see a plane overhead and something is going to come out of the back, and that will be weed killer, and it will kill all the weeds in the cotton field. That means that nobody will be chopping cotton this spring. Then, this fall, you’re going to see a machine go up and down the rows of cotton, and that will be an automatic cotton-picker. And that means there will be nobody picking cotton this fall. That airplane and that cotton-picker together are automation. Now, everybody say “Automation.” “Automation” means that a lot of people won’t be eating this winter. But don’t go to Chicago, because you won’t be eating there, either. So we’ll set up a food program to hold you for a while, and we’ll organize and see what we can do.’ ”

After three years of such efforts, Moses does not have to be told that any significant improvement in either the economic or the political lot of Mississippi Negroes is going to require changes from the outside. The Summer Project was set up as one way to go about getting them. In the eyes of some of the S.N.C.C. leaders, the Project, which grew out of the participation of Yale and Stanford students in a mock election last fall, had certain drawbacks. There were fears of efficient, well-educated Northern whites’ taking over the movement, of undermining the painfully built self-confidence of Mississippi Negroes through receiving help from whites, and of a strong backlash when the volunteers left. Countering these fears was a realization not only of all the work that five or six hundred volunteers could do but of the remarkable opportunity that the Summer Project presented for drawing the rest of the country into some involvement with Mississippi rather than a casual dismissal of the state as hopeless. Over the past year or two, S.N.C.C. leaders have found that the personal involvement of Northern whites—and particularly of well-educated, well-connected Northern whites—creates a pressure that would otherwise be missing. “We’ve operated in the past three years on the theory that the two things the local segregationists don’t want are more federal involvement in any way at all and more public focus,” Forman says. “Our problem is how to get the government to do what it’s supposed to do. How can you get the Justice Department to press certain suits, for instance? One way is to make a lot of noise about the fact that they’re not doing it, create a public consensus, get people to call in about it, and make it easier for the government to act. It’s a question of balancing opposing forces.”

Federal involvement—or federal intervention, or federal presence—is a much discussed subject in Jackson, and most people close to cofo believe that what its leaders are divided over is not whether or not federal involvement is desirable but simply what form it should take and what should be done to get it. Almost everybody in cofo denies any desire to see federal military occupation, and it is often pointed out that having a hundred and fifty F.B.I. agents in the state this summer, instead of a mere fifteen or so, even if they keep insisting that they are not there to protect anybody, is a huge increase in federal presence. The theory advanced by some Northern columnists and editorialists after the disappearance of the three murdered civil-rights workers in Philadelphia that the summer volunteers are being used as unwitting martyrs to provoke federal intervention infuriates even Moses, whose composure is ordinarily awesome. Having been in Mississippi for three years, virtually by himself and almost completely ignored, Moses is understandably irritated at the implication that he is a Machiavellian who sits in an office somewhere coldly sending innocents to the slaughter. cofo leaders point out that the Summer Project volunteers were repeatedly warned ahead of time of the dangers they would be facing, that they are not sent to places where violence is considered to be what Moses calls “repeatable” (the southwest area of the state, around Natchez, is such an area), and that a good deal of time is spent in setting up elaborate security arrangements. Still, they acknowledge that protection for Negroes in Mississippi is likely to be provided only when whites are involved and that ordinary pressures, such as publicizing incidents and writing to congressmen, would probably not have brought in the F.B.I. if the murders had not occurred. No sophisticated study of public opinion needed to establish the fact that in the United States, North or South, white life is considered to be of more value than a Negro life. In the mimeographed newspaper published by the cofo Freedom School in Holly Springs, a local girl wrote, “When we heard about the three freedom workers missing we were hurt but not shocked because many of our people have come up missing and nothing was said or done about it. Ever since I can remember I have been told of such cases from my people. But never have I heard it said on the news or over the T.V. or radio.”

In discussing federal involvement, S.N.C.C. people tend to go no further with specific suggestions than Forman’s statement that the government ought to do “what it’s supposed to do.” Moses says, “It’s not our function to decide what form federal pressure should take; it’s our function to holler loud, and that’s what we do. It’s a matter of whether Americans have the right to vote. I don’t see how the country can come out with a negative answer—unless Goldwater gets in. We want to demonstrate to the Negro community, the country, the federal government. The presence of the F.B.I. in Mississippi is a big step. If they’re not able to maintain control, the symbolic presence of marshals may be needed in the worst counties. The point is that the fact of the terror is out in the open, and the country has to do something about that.” Moses believes that a breakthrough could come through litigation that would eventually result in a court ruling supporting S.N.C.C.’s thesis of “One Man, One Vote.” He has particular faith in a favorable decision on the case of U.S. v. Mississippi, a suit that has been instituted by the Justice Department and that would result in the elimination of most of the legal obstacles to Negro registration. Moses has also been heartened by a recent decision in Panola County, where a federal judge invoked what is known as “the freeze theory” for the first time, ordering the county registrar to ignore the prescribed voting tests for Negroes for a period of a year, on the ground that the tests had been ignored for a number of years in the registration of whites. Favorable action on U.S. v. Mississippi would take at least a year—it is now on appeal to the Supreme Court after being dismissed by a three-judge federal court in Mississippi—and freeze-theory rulings would have to be based on evidence in eighty-two separate suits, one for each of Mississippi’s eighty-two counties. Moses seems prepared to wait—despite the idealism implied by his presence in Mississippi, he gives the impression of being a remarkably realistic man—but even his patience has limits. Upon being asked what he would do if a favorable ruling on U.S. v. Mississippi did not serve to stop the subterfuge and intimidation, he said, “We’d set up our own election, call in observers, and ask that we be recognized as the true government of Mississippi.”

Other members of cofo are still less patient, and many people who are basically sympathetic to the Summer Project believe that some of those involved in it welcome the antagonism of Mississippi whites as the best way to get large-scale federal intervention—or occupation. “I think some of them would do just about anything to get massive federal intervention,” one such observer said not long ago. “That’s what they want, consciously or unconsciously. They have some fancy words for it—showing the nation the evil, bringing the hostility to the surface—and they won’t go outside the bounds of the voting drive to achieve it, but basically it amounts to provoking Mississippi into doing something that the federal government won’t take. Why? Maybe they’re just tired. Maybe they just want to bring everything to a head after all this. Sometimes I can’t blame them.”

Whatever the reason, the emphasis on violence and arrests is so great at the cofo office in Jackson that a stranger could spend hours there without being aware that a voter-registration drive was being carried on throughout Mississippi, that nearly fifty Freedom Schools are operating in the state, or that a new political party is being organized. About the time of King’s visit, voter-registration workers began to concentrate on the mock registration for the Freedom Democratic Party, so that its delegates could demonstrate to the Democratic Convention how many people they represented, but a chart on the rear wall of the office that was supposed to show the registration results by counties was never used, and until a small notice went up on the bulletin board a few days after King left the state there was no indication at all of how the campaign was faring. The Party was being organized from the precinct level up, and several cofo workers who attended a county meeting near Canton, north of Jackson, the day after King left returned bubbling with enthusiasm. But the next day the blackboard on the front wall of the cofo headquarters said nothing of the fact that three hundred Negroes had attended a meeting of the Freedom Democratic Party, instead offering the usual reports of violence: “Batesville 1:00 a.m. Freedom House had tear gas grenade thrown into it. . . . Occupants vacated house. McComb 1:30 a.m. House of N.A.A.C.P. prex had two packages of dynamite thrown at it. . . . No injuries. . . . Damage slight. Tchula 3:00 a.m. S.N.C.C. automobile set afire. ⅔ burned. . . . Interior gutted.”

Other members of cofo are still less patient, and many people who are basically sympathetic to the Summer Project believe that some of those involved in it welcome the antagonism of Mississippi whites as the best way to get large-scale federal intervention—or occupation. “I think some of them would do just about anything to get massive federal intervention,” one such observer said not long ago. “That’s what they want, consciously or unconsciously. They have some fancy words for it—showing the nation the evil, bringing the hostility to the surface—and they won’t go outside the bounds of the voting drive to achieve it, but basically it amounts to provoking Mississippi into doing something that the federal government won’t take. Why? Maybe they’re just tired. Maybe they just want to bring everything to a head after all this. Sometimes I can’t blame them.”

Whatever the reason, the emphasis on violence and arrests is so great at the cofo office in Jackson that a stranger could spend hours there without being aware that a voter-registration drive was being carried on throughout Mississippi, that nearly fifty Freedom Schools are operating in the state, or that a new political party is being organized. About the time of King’s visit, voter-registration workers began to concentrate on the mock registration for the Freedom Democratic Party, so that its delegates could demonstrate to the Democratic Convention how many people they represented, but a chart on the rear wall of the office that was supposed to show the registration results by counties was never used, and until a small notice went up on the bulletin board a few days after King left the state there was no indication at all of how the campaign was faring. The Party was being organized from the precinct level up, and several cofo workers who attended a county meeting near Canton, north of Jackson, the day after King left returned bubbling with enthusiasm. But the next day the blackboard on the front wall of the cofo headquarters said nothing of the fact that three hundred Negroes had attended a meeting of the Freedom Democratic Party, instead offering the usual reports of violence: “Batesville 1:00 a.m. Freedom House had tear gas grenade thrown into it. . . . Occupants vacated house. McComb 1:30 a.m. House of N.A.A.C.P. prex had two packages of dynamite thrown at it. . . . No injuries. . . . Damage slight. Tchula 3:00 a.m. S.N.C.C. automobile set afire. ⅔ burned. . . . Interior gutted.”

S.N.C.C. leaders believe that they can see some progress in Mississippi when it is compared with the monolith of segregation Moses found in 1961. “All other civil-rights groups considered Mississippi hopeless,” Forman says. “Now at least a beachhead has been established. We’ve got organizations all over the state. We’ve been forming a basis all the time for the Justice Department’s voting suits. We’ve changed the atmosphere in the Negro community. And we’re getting more resources, more people, and a consensus that something is wrong. By plugging away, you get the National Council of Churches involved, you get people building community centers, you get things like the Harvard summer teaching project at Tougaloo College, you get white Northern lawyers talking to some of these people for the first time.”

The success of cofo depends partly on how consistently its projects are carried on after the summer is over—some of the volunteers are expected to stay on, and Moses, who sees his commitment in terms of “three-year hitches,” plans to remain in Mississippi until 1967—but even if the projects thrive, and even if some breakthroughs in litigation are made, it is likely to be a long time before a cofo worker can see that his efforts have had any substantial effect on the state. “I think that concern over civil rights moves by plateaus, and we had to make sure Mississippi got in on this move,” Moses says. “But this commitment has to be for the long haul. People say ‘Why are you doing this?’ or ‘Why are you starting with this aspect?’ or ‘Where can this approach ever get you?’ And we say ‘What else would you have us do?’ ” ♦

— Published in the print edition of the August 29, 1964, issue, with the headline “Plane to Mississippi.”

— Calvin Trillin, A Staff Writer, has contributed to The New Yorker since 1963. His many books include “Jackson, 1964” and “About Alice.”

— The New Yorker

0 notes

Text

Flip Schulke, Namu, the killer whale, Puget Sound, 1966.

“La cámara es como un muro entre tú y el peligro y te arriesgas… Llegué a un punto en el que decidí que si iba a arriesgar mi vida, tenía que ser por algo en lo que realmente creía profundamente”.

Flip Schulke

1 note

·

View note

Text

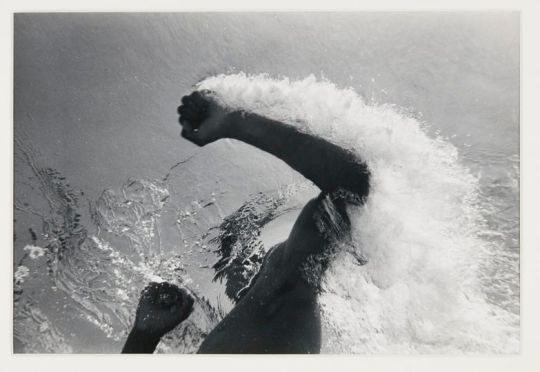

Muhammad Ali por Flip Schulke // 1961

Mãos do Miles Davis por Irving Penn // 1986

0 notes