#Eric wetherell

Link

0 notes

Photo

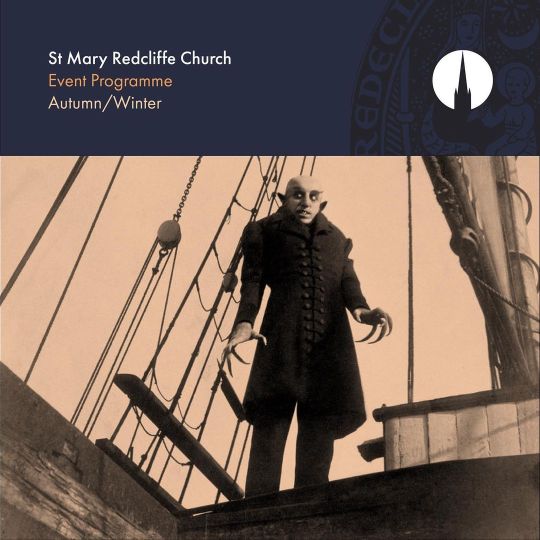

Autumn/Winter Event Programme - We have an exciting series of special events taking place at #stmaryredcliffe this November and December. On Sat 5 Nov there’ll be a centenary screening of the expressionist classic ‘Nosferatu’ as part of @bristolfilmfestival; on Fri 18 Nov ‘The Bishop’s Wife’ starring #carygrant will be showing as part of the @carycomeshome film festival; on Sat 19 Nov we’re hosting ‘Remembering’ - a concert celebrating the life and music of renowned composer Eric Wetherell - proceeds of which will go towards @stpetershospice; and on Wed 7 Dec, we’ll be hosting a candlelit concert, ‘Vivaldi’s Four Seasons at Christmas’ featuring @piccadilly_sinfonietta - Links to info and tickets via link in bio (at St Mary Redcliffe) https://www.instagram.com/p/CjtEDtpsUqq/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Eric Wetherell Death - Obituary | Eric Wetherell Dead - Passed Away

Eric Wetherell Death - Dead, Obituary, Funeral, Cause Of Death, Passed Away: On February 5th, 2021, InsideEko Media learned about the death of Eric Wetherell through social media publications made on Twitter. Click to read and leave tributes

Eric Wetherell Death – Dead, Obituary, Funeral, Cause Of Death, Passed Away: On February 5th, 2021, InsideEko Media learned about the death of Eric Wetherell through social media publications made on Twitter.

InsideEko is yet to confirm Eric Wetherell’s cause of death as no health issues, accident or other causes of death have been learned to be associated with the passing.

This death has caused…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

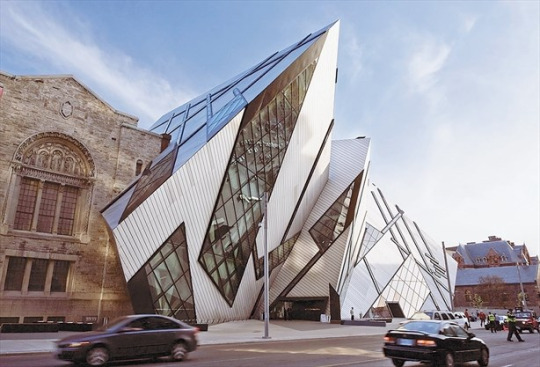

Things to do this week in Toronto

What's happening in Toronto April 15-19, 2019

MONDAY, APRIL 15

3rd Monday Nights Free at the Royal Ontario Museum: Bring family and friends to the ROM on the 3rd Monday Night of each month and enjoy free admission from 5:30 pm to 8:30 pm.

Education Town Hall with Ontario NDP Leader Andrea Horwath: Discuss the impact of Doug Ford’s education changes. This is a free event and the venue is accessible. Light refreshments will be served.

TechTO April Edition at RBC WaterPark Place: Join the TechTO Community to meet and learn from Toronto’s technology leaders, innovators, and enthusiasts.

Pop Music : Better Now or Better Then? Is music better now or was it better back in the day? We play a new number one hit, then pick a random year out of a hat and play the number one hit from that year and let the audience decide: better now or better then?

Etobicoke Camera Club presents Rob Stimpson: The Challenges (and Rewards) of Travel Photography: professional photographer, Rob Stimpson, will discuss capturing images on the go focussing on the challenges and rewards of travel. Guest fee of $10.00 in effect for non-club members.

Jaymz Bee's Caravan of Music at Old Mill Toronto: Jaymz Bee’s Caravan of Music is a four hour event where you can explore the various rooms at Old Mill Toronto. Experience 20 bands in 10 rooms. Proceeds will support the Unison Benevolent Fund.

Eric Andersen and Scarlet Rivera: Performing at Hugh's Room Live. Doors open at 6 p.m., concert at 7:30 p.m.

'This Is Me' at Fairview Library Theatre: showcases talented artists from Centennial Colleges PAFS before they make their leap into stardom.

TUESDAY, APRIL 16

Humber Docs Film Screening at The Assembly Hall

Humber College School of Media Studies and IT would like to cordially invite you to the annual Humber Docs Screening, showcasing the documentary film work of the Third Year Bachelor of Film and Media Studies Students. Free admission.

ALSO ON TUESDAY

Toronto Lit Up: Alexandra Kimball at The Ossington: Alexandra Kimball is releasing The Seed: How the Feminist Movement Fails Infertile Women and will be celebrating its publication with a Toronto Lit Up book launch.

Canadian Children's Opera Company's Junior Open House: Does your child love music, drama, and theatre? The CCOC is just who they're looking for. Join them to find out what a CCOC music education looks like and learn about our programs for kids aged five and up.

F*ck Sh*t Up: Trans + Non-Binary Cabaret: A night of performances by trans and non-binary artists and performers! Featuring M A N G O S A S S I, Ravyn Wngs, Robbie Ahmed, Ben Agiter and Velvet Earl. Hosted by Babia Majora and Fluffy Soufflé.

Pro-Case Tuesdays at Absolute Comedy Toronto: Event features headliner Tommy Savitt and host Alastair McAlastair, with Joe Vu, Noor Kidwai, Perry Perlmutar, Rhiannon Archer and Sam Feldman.

Kelvin Wetherell at Cafe Mirage: Cafe Mirage Grill and Lounge presents Kelvin Wetherell on Nov 6. The performance runs between 8:00 pm to 11:00 pm in the evenings with a 15 minutes break in between. Cafe Mirage is one of the leading restaurants in Scarborough.

Hot Breath Karaoke at The Handlebar: Ridiculous game show style karaoke, with prizes.

Westway Christian Church Food Bank: The Westway Christian Church Community Food Bank is open for clients to receive food on Tuesday evenings from 5-7 p.m.

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 17

Caught in the Net by Ray Cooney

Teens Gavin and Vicki happen to meet surfing the internet. They are attracted to each other and yet are amazed by all the coincidences — each having a father with the same name, same age, and same occupation. Why? Find out in this farce.

ALSO ON WEDNESDAY

2019 Cannabis Capital Conference: Benzinga is the go-to source for investors who need the latest news in the cannabis sector. This is the event that connects companies with investors.

Coloured bodies: Material Moves by Dori Vanderheyden: Dori Vanderheyden’s work layers and enfolds themes of sexuality, the body and colour as a way to evoke questions of what it means to be a human in the universe at this time.

OCAD University’s President’s Speaker Series presents: Burton Krame: Kramer was a professor at OCAD University for over 20 years and in 2003 was one of the first to receive an honorary doctorate from the institution.

'My Father's Son' releases new single at The Dakota Tavern: Montreal's 'My Father's Son' releases his new single, "Ribbon in the Wind", ahead of his second full-length album, The Greatest Thaw.

Who run the world? QTBIPOC: A free drop-in workshop series on relationships for youth. Learn skills and connect with other 2SLGBTQ Black, Indigenous and youth of colour (16-29) at this Beyonce-themed workshop series on relationships-- with pals, family, partners and yourself.

Off The Rails Comedy Competition at Comedy Bar: 'Off The Rails Comedy' is an interactive, improvised stand up show where Toronto's bravest comics make up their acts based on your suggestions! You have the power!

Christian Bernard Singer and Heidi Leverty: HABITAT: In this exhibition we bring together two artists whose artistic practice embraces our relationship with our Habitat, the exhibited works create a striking narrative between the chaotic and the sublime.

The Liveable City? Transportation: As Impressionism in the Age of Industry takes viewers on a journey through a period of immense change in 19th century Paris, we invite speakers across various disciplines to enter into conversations around urgent issues facing Toronto today.

Chocolate Groove: A weekly social dance celebration featuring Toronto’s best DJ’s in one of the most visionary alternative venues in Canada: Alternity.

THURSDAY, APRIL 18

Great Art: Rembrandt in Black and White: The Printmaker

Art historian Anne Thackray shows how Rembrandt’s immensely creative and fertile imagination embraced the expressive possibilities of prints, the most widespread art form of his times.

ALSO ON THURSDAY

Toward environmental rights in Canada: A panel discussion: To mark Earth Week, educators, activists and thought-leaders will convene for a half-day symposium on environmental rights. The event will map a rights-based approach to climate, water and health challenges in Canada.

The Experiment at Comedy Bar: Come see a hilarious improv show featuring performers from CBC's Workin' Moms, Baroness Von Sketch, Sunnyside, and Netflix's Umbrella Academy!

Sketch Swap Showcase: The best of Toronto's Sketch Comedy Scene will be performing the best sketches seen on Toronto stages in the last year and they're not allowed to do their own material! A fun night full of laughs, drinking, and stupidity!

Casual Chess Club at Beaches Library: Join other chess players in a friendly and welcoming environment for casual play. All ages and skill levels are welcome.

Online Reputation Management with Veronica Chail: The CEO of VC Strategies examines the current online culture and provides tools to help you: Curate content that aligns with your brand; Build trust with your audience; Monitor your reputation; and React promptly to avoid crises.

Rock for Dimes Toronto 2019: The annual fundraiser supports MODC's After Stroke suite of programs. Acts include Fresh Water Sharks, Oui B. Jamon, Bit o' Brit Collective, Martha Rocks and Envy & The Cants. Maie pauts of boom 97.3 will host.

Earth Love & Learn - Yoga, Meditation & Earth Talk: Join Irina Andreea and Cassidy Thedorf for this celebration of earth day. A portion of proceeds will be donate to One Tree Planted to help support global reforestation.

RuPaul's Drag Race Viewing Parties: Fans of the hit reality television series can watch new episodes every Thursday at several spots around the city, including The Gladstone Hotel, The Beaver and Striker.

FRIDAY, APRIL 19 (GOOD FRIDAY)

The Toronto Passion Play at Church on the Queensway

The Christian Performing Arts Centre presents 'The Toronto Passion Play' this Easter Season. This spectacular musical depicts the life of Christ, in a brand new riveting story that is sure to delight and please audiences of all ages. April 19-21.

ALSO ON FRIDAY

Mike Rita's 'Pot Comic' album release party: A fresh voice in a haze-filled room, Mike Rita's Pot Comic riffs on being at the forefront of the “weed generation”, how his mom came to love pot, and the hilarious ways in which legalization has changed Canadian lives.

Hey Girl Hey: Bad Friday! Come get bad with us at The Baby G at your fave queer hip-hop and r&b dance party celebrating female and non-binary artists.

International Fan Festival Toronto at Metro Toronto Convention Centre: International Fan Festival Toronto is the newest Anime Convention in Toronto. IFF Toronto is a multi-day, multi-fandom, Japanese focused event. Our featured events include, exclusive Fate/ stay night talk shows with the main casts of the series.

Kidnetix 13th Annual Easter Egg Hunt: Egg-citement for the whole family! Hunt for thousands of Easter candies in our indoor playground. Free photo booth with the Easter Bunny. Crafts, fun interactive petting zoo, and video game theatre.

Friday Night Jazz at Ripley's Aquarium of Canada: Explore the waters of the world the second Friday of every month with live jazz music as you sip on a drink (alcoholic and non-alcoholic available) under the sea.

C'mon, Angie! at The Assembly Theatre: Told with humour, heart, and unflinching honesty, C’mon Angie! is a new play by Amy Lee Lavoie that dramatizes a difficult and all-too familiar situation, as two character navigate consent and sexual assault following a one-night stand.

Brooklynn Bar Comedy: We’ve put together some of the best Pro Comedians in the city with help from 'Perfect 10 Comedy' for a VIP comedy show.

Redwood Comedy Cafe: A weekly comedy showcase featuring Canada's top comedians at the intimate Redwood Cafe in Little India.

After Hours: Comedy Bar's beloved late night ensemble party show returns with a fun lineup of some of Toronto's favourite stand ups.

ONGOING

Annual Beaches Easter Parade Weekend: Easter weekend celebration includes: Good Friday Easter Egg Hunt at Kew Gardens, which includes children's entertainment and a meet and greet with Peppa Pig. Easter Sunday Parade on Sunday at 2p.m. along Queen Street East.

Neighbourhood Trust at Lakeshore Arts: A collaborative project examining the state of affordable housing in Toronto through the lens of those directly affected. Runs until April 18.

Angélique at Factory Theatre: Inspired by historical transcripts from the infamous trial, Angélique is a moving account of Black Canadian history beyond the Underground Railroad.

Winter Stations 2019: Featuring six unique art installations. Runs until April 21.

Art Show & Sale by Marley Berot at Starving Artist Restaurant: Trini-Ja Canadian Marley Berot is opening her first show at the Starving Artist Restaurant and Gallery at 467 Danforth Avenue. Her acrylic paintings will stay on the walls until May 18th.

PRECIOUS: An Exhibition of Contemporary Art and Jewellery: By creating precious artwork and art jewellery from everyday and discarded items, Micah Adams, Christine Dwane and Lawrence Woodford remind us that our world is shaped by the decisions we make. Whether disposable or sustainable, beauty is everywhere. On display through May 23.

Being Japanese Canadian: Reflections on a Broken World at the ROM: Explore the original exhibition through the eyes of curators Bryce Kanbara and Katherine Yamashita. Runs until May 25.

The post “ Things to do this week in Toronto “ was originally seen on toronto.com by Whatson

IV Vitamin Drip Therapy Toronto Clinic - The IV Lounge

0 notes

Text

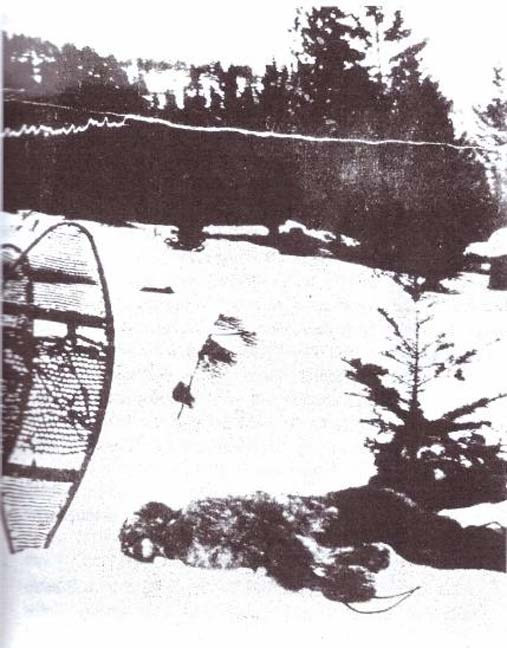

Project 6; the unexplained

for project 6 we had to choose from a list of ‘unexplained’ phenomenons to base our work around. I chose cryptids and cryptozoology.

Cryptozoology is the pseudoscience and study of creatures whose existence has not yet been proven (the study of hidden animals). The creatures, nicknamed cryptids, are usually sited in folklore. There is a subculture of cryptid fanatics that try to prove the existence of these creatures, giving evidence in the form of photographs, videos, or simply relaying stories, however so far all modern examples of these have been hoaxes.

The most notable cryptids include;

Bigfoot

Originating from the Pacific Northwest of America is the Bigfoot (or sasquatch) a very hairy bipedal ape like creature that is between 7 to 9 foot in height.

The first alleged sighting for this creature was in 1811 by a man called David Thompson in Canada. He found footprints in the snow that were fourteen inches long and eight inches wide, with only four toes.

The first image above is believed to be the first photograph of Bigfoot, shot in 1894 by two mountain men, once again in Canada. They encountered the animal and shot it before taking the photo.

The second photo is a still from a video, which was a short motion picture created by Roger Patterson and Robert Gimlin shot in 1967. The video is shakey and is very low quality, and depicts an a nature scene in the woods with an unidentified ape like animal walking in the distance. The filmmakers claimed this animal to be bigfoot, and since the time it was shot many people have tried to debunk this myth, however Patterson claimed that it was real right up until he died.

In 2002, a costume maker by the name of Philip Morris claimed that he made the gorilla costume, and that is what was used in the film by Patterson and Gimlin, but this was never officially confirmed.

A similar creature was reported in November 1951, by an adventuring expedition group were scaling Mount Everest, and found the imprint of a large foot not resembling any known man or beasts footprint, and so Eric Shipton took a photograph of the imprint, with his icepick next to it for scale.

video of sighting

Loch Ness Monster

Nessie, or the Loch Ness Monster, is a monster claimed to inhabit the Scottish Loch Ness, and has been described as being lizard like with a long neck and an arched back, possibly with more than one hump.

The first sighting appeared in 1933, by a Londoner and his wife who reported seeing 'the nearest thing to a dragon or pre-historic animal' that was walking across the road to the Loch. This report was published in the Courier newspaper and soon after, many other claims started flooding in.

A few months later, the first alleged photograph of the monster was taken by Robert Kenneth Wilson and later published in the Daily Mail, however Wilson didn't want his name associated with the photograph so it was published under the guise of 'surgeons photograph'. Wilson took four photos when he first saw the creature, but two came out blurry.

In 1994 the photos were exposed as a hoax by the stepson of Marmaduke Wetherell, who had arranged the stunt with Wilson. The Nessie in the photos was just a toy submarine with a toy snake head attached to it.

Regardless of that photo though, many claims of sightings of Nessie have still been reported since then. In 2003 The BBC even funded an extensive search in the Loch, but no findings were reported.

Mermaid

Mermaids boderline mythical creature more than cryptid, but I thought they were worth mentioning due to their increasing popularity and various hoaxes. Mermaids are a legendary creature which is human on the top half of their body, however instead of having legs they instead have the tail of a fish. They have been frequently mentioned all throughout history, such as the sirens who drowned sailors featured in Greek mythology, the ancient story of Goddess Atargatis who transofmred herself into a mermaid, or the sighting claimed by explorer John Smith in 1614 of a mermaid with green hair.

Alongside that, mermaids have also been becoming increasingly popular in literature and pop culture, such as Hans Christian Andersons 'The Little Mermaid' written in 1836, which would later be adapted to a animated feature film by Disney studios. Mermaids particularly are popular amongst small girls, with plenty of toys and cartoons in the image of a mermaid with young girls as the target audience.

But are they real? A lot of people have come forward with shocking 'evidence', such as the body of a real live mermaid! Well, not live. The usual claim for these bodies is that the person claimed they found it washed up on the shore.

This was an example which is currently displayed in the Booth Museum here in Brighton, which is part taxidermied monkey and fish, and also some of it is sculpted from wood. It looks like a pretty convincing mermaid but was obviously proven as a hoax. There are a lot of similar claims for 'found creatures' with bodies made of similar components, these types of fake mermaids have been named the Fiji Mermaids.

Similiarly, there is another cryptid that reminds me of mermaids called the Sea Monk, who is a scaley man like creature who looks similar to a monk or a bishop.

Fairies:

Fairies (or fae), similar to mermaids, are more mythical creatures than cryptids, featured in many folkstories and legends throughout all of time with no single origin. But again, I thought they were worth mentioning due to a very famous hoax involving them.

Fairies are claimed to be alike humans, except very small, with the ability to fly with wings on their backs. They are also depicted to be magical and mischevious, prone to trickery on mortal humans. Many tales of fairies include them stealing babies away and taking them to the world of the fae. The world of the fae also has an entire lore behind it, such as if you step into a circle of toadstools you will be teleported there, and if you eat any of the fairies foods you will never be able to leave.

One of the most famous hoax stories occured in 1917 by two young cousins from England. Elsie Wright and her younger cousin Frances Griffiths often played by the beck (stream) at the end of their garden, and claimed it was so they could see the fairies that lived there. One day they took photos of the 'fairies' as evidence using Elsies fathers camera. Her father didn't believe the photographs were real, however her mother Polly did, and in 1919 showed them to her Theosophical Society meeting, the following year Sir Arthur Conan Doyle came to the attention of the photos and soon published them in The Strand Magazine, causing public uproar. There were mixed reactions to the authenticity of the photos.

60 years later in 1980, both Frances and Elsie admitted the photographs were faked, using cardboard cutouts from a childrens book.

useful links;

http://cryptidz.wikia.com/wiki/History_of_Cryptozoology_Timeline

http://www.relativelyinteresting.com/the-monstrous-compendium-of-cryptids-and-creatures/

http://www.unmuseum.org/bigfoot.htm

https://www.outsideonline.com/2097161/10-most-convincing-bigfoot-sightings

http://www.relativelyinteresting.com/heres-what-the-bigfoot-patterson-gimlin-film-looks-like-when-its-stabilized/

https://listverse.com/2010/08/13/top-10-cryptids-that-turned-out-to-be-real/

https://io9.gizmodo.com/a-field-guide-to-cryptids-from-europe-and-africa-595809722

https://factandsciencefiction.com/cryptids/

http://www.relativelyinteresting.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/what-is-cryptozoology.jpg

0 notes

Text

Jonathan Scourfield et al., The non-display of authentic distress: public-private dualism in young people’s discursive construction of self-harm, 33 Sociol Health & Illn 777 (2011)

Abstract

This article draws from focus groups and interviews investigating how young people talk about self-harm. Some of the research participants had personal experience of self-harm but this was not a prerequisite for their inclusion in the study. Thematic coding was used initially to organise and give an overview of the data, but the data were subsequently analysed using a discourse analytic approach. The article focuses on the young people’s constructions of deliberate self-harm such as ‘cutting’. Throughout the focus groups and interviews, a dichotomy was set up by the young people between authentic, private self-harm which is rooted in real distress (and warrants a sympathetic response) and public, self-indulgent attempts to seek attention. This dualistic construction is discussed in some detail and located in various socio-cultural contexts. It is argued that the dualism illustrates contemporary ambivalence about mental health and youth.

Introduction

Much of social life depends on display; the public show of behavioural and stylistic signs through which identity is claimed and ascribed (Finch 2007). In the west, display is perhaps especially associated with youth. Youth can be a time for spectacular displ`ants set up in relation to self-harm. In order to develop our argument and lead to a coherent conclusion, we present the main research findings and then pause for a discussion section before returning to the data to show how the public-private dualism is challenged by one interviewee. Before moving on to give a thematic overview of the data on public and private self-harm, the research strategy will now be summarised.

Research methods

The empirical basis for the article is a qualitative research project conducted in South Wales and the North of England in 2005–2006. This project’s title for participants was the ‘On the Edge’ project and it was presented as being about ‘young people in distress’. One of the main research objectives was to identify and analyse the discursive frames through which young people make sense of suicide and self-harm. This article in fact deals specifically with the discursive construction of self-harm and not suicide. Our analysis of the discursive frames through which young people make sense of suicide has been presented elsewhere (Roen et al. 2008).

Focus groups and interviews were conducted with young people aged 16–25. There were 13 interviewees and 66 young people took part in 11 focus groups. Most of those interviewed had already attended focus groups, so the total number of individuals taking part in the research was 69. Around twice the number of focus groups and interviews took place in the North of England as in South Wales. A purposive sampling strategy was used in an attempt to reflect diversity of ethnicity, social class, sexual identity and rural and urban location. There was no targeting of young people with direct experience of self-harm or suicide, as the intention was to speak to a more general population of young people. Despite this, some young people did seem to have volunteered to take part in the project because of personal contact with self-harm or suicide and this is more or less inevitable. The majority of interviewees and focus group participants had known someone who had ‘attempted suicide’. This was the phrase used on a short demographic questionnaire participants completed at the end of the focus group or interview. We did not specifically ask in this questionnaire about participants’ relationship to ‘self-harm’ but instead draw our analysis from the participants’ discussion of this topic.

Participants were recruited via schools, colleges, universities, youth clubs and social welfare organisations. We ensured that a trusted support worker was available on site for participants and provided information on sources of support following interviews and focus groups. Ethical approval was granted by the research ethics committee of the Lancaster University Institute of Health Research. To protect the identities of research participants, all names used in this article are pseudonyms.

The article is structured into three empirical sections. First, there is an overview of the data on non-fatal self-harm which were retrieved by thematic coding. Coding using Atlas-ti software enabled all references to non-fatal self-harm to be identified. These were subsequently analysed for thematic content and the results of this analysis are presented in the first empirical section. In the second and third empirical sections we present more detailed discussion of two specific passages of talk, to examine the discursive strategies employed in relation to self-harm and describe their effects. In using the terms ‘discourse’ and ‘discursive’, we refer to an interpretation which is culturally authoritative and constrains what can be thought and what can be done (Foucault 1980). Our approach to discourse analysis is consistent with that found in critical psychological research (Hollway 1989, Wetherell and Edley 1999), and more specifically, we use the strategies outlined by Willig’s (2003) account of discourse analysis, as well as those of Hook (2001) who offers a critical engagement with the possibilities of Foucauldian discourse analysis. To explain the process of collaborative analysis, all three authors contributed to initial coding, though most was done by Liz McDermott, who was the researcher employed full-time on the project. Some specific passages of talk, including those discussed in later sections of this article, were then identified as fruitful for more detailed discourse analysis and these were the subject of lengthy discussions at research team meetings, with notes being typed up to record the emerging analytic ideas.

Thematic overview of young people’s views on self-harm

The key finding addressed in this article is that self-harm was taken by the young people in our study to mean different things depending on whether it is private or public. There was a clear dualism underpinning their understanding of self-harm. ‘Cutting’ was the form of self-harm they most frequently cited. The idea was that, if kept private, cutting suggests serious distress and real psychological and emotional pain. On the other hand, any public display to peers was thought to undermine its credibility. If you can see it, the reasoning went, the person concerned must have meant you to see it, and this means their behaviour must therefore be ‘attention-seeking’– a highly negative term for them which suggests demanding more attention than is deserved or more attention than is warranted by the distress experienced. The following excerpts are illustrative of comments that appeared across the focus groups and interviews.

Eric :They tend to show it off more, you know, like you said there, showing off the cuts and that, if someone’s depressed they try and hide it as much as possible you know they try and isolate themselves from the world (Focus group – lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender [LGBT] project, small town, North of England1).

Gwen: But like if you’re addicted you sort of try hiding. You’re like in denial. ‘Oh I’m, I’m not doing that. I don’t know why […]’ But like if you show it, like not show it off but you know like making people aware, I think it’s sort of like, I, I think it is attention (Focus group – comprehensive school in South Wales town).

Rachel: That’s true because in my first year I lived with a boy and he obviously used to cut himself but he used to walk around with like you know like um sleeveless tops and things and I could see like scars all down his arms and you’d just like, if he’d done it as a way to cope or as Rita said trying to forget something painful then why would he want everyone to know that he’d done it? Just seemed weird (Focus group – university in the North of England).

Jack :I’ve just finished doing this course called the [name edited out] and early on in the course there was a girl who got kicked off um and she cut her wrists and everything just to try to get back on to the team and it was just so pathetic but she did it and um

Liz (researcher): How did, sorry?

Jack: At least I could see now it was for attention (Focus group – LGBT project, South Wales).

So people who are ‘addicted’ to cutting or ‘depressed’ or who need to ‘forget something painful’ will want to hide their behaviour and keep it secret, whereas to make sure that one’s cuts are seen is to ‘show off’. Often the accusation of attention-seeking was made and not elaborated on, suggesting the speaker presumed there was a shared meaning. However, in the following data excerpt, Christopher is more explicit, telling us that attention-seeking implies the exaggeration of symptoms to achieve the desired result – something we have ‘all done’.

Christopher: I mean I think we’ve all done, not cut our wrists maybe but we’ve all done, you know, made our problems seem a little bit worse to try and get people to just look after us you know (Focus group – Further Education college, town, North West England).

Both public and private self-harming are gendered in the young people’s accounts. They are associated with girls in particular, and (less often) with feminised men, and an example is presented later in the article of an account where self-harm is associated particularly with working class girls. One of the reasons that public/visible self-harm is not generally seen as denoting serious distress is that the young people described it as being glamorised. It is fashionable; it gets copied. Jane, an interviewee from South Wales, was worried by the approving reactions some people had shown when they noticed her scars. She said she had done some modelling and the make-up artist had said ‘oh, nice scars!’ When asked why such positive reactions occur, Jane said she thought some people thought the scars ‘hard core’ and ‘some people find it quite fascinating and kind of macabre’. She went on:

Jane: Just certain people are definitely drawn to fucked up-ness, and drawn to well just things which are a little bit weird, a little bit odd, a little bit different, or, or which clearly states that you’ve been through shit of some sort (Interview, South Wales).

As evidence of its contagious glamour, Jane gave us an example of how ‘self-harm does spread in institutions’. She spoke of having lived in a hostel where ‘15 out of 31 of us’ were self-harming. She regarded this as ‘copycat’ behaviour. Another recurring theme in relation to the fashionable status of self-harm was its association with particular sub-cultures, especially ‘Goths’ and ‘Emos’.

The dichotomised understandings of self-harm, as being either for genuine reasons (and hidden), or for attention (and visible in front of peers), have also been highlighted in other qualitative research with young people. Crouch and Wright (2004) interviewed young people who had personal experience of self-harming, and who were living in a mental health unit at the time of the study. According to their data, ‘the non-secret self-harmers were despised’ (2004: 193) by other young people on the unit because they were viewed as being ‘attention-seeking’ and ‘as somewhat pathetic’ (2004: 194). This structuring of understandings about seeking attention may lead to a sense that there is ‘a competition to be the most genuine self-harmer’ (2004: 195). Spandler (1996) also engages with this dichotomy and the conflicts it presents for young people who self-harm. Specifically, these are conflicts between wanting someone to listen but not feeling able to communicate that, and wanting attention but not feeling one deserves such attention. Clearly, the need to communicate about emotional difficulties – the need to ask for help – is complicated by dichotomous understandings of self-harm.

In our data set there were only two ways in which the private-good/public-bad dualism was undermined. First, there was a suggestion that those who make their self-harm visible may genuinely be in emotional difficulty, with participants asking ‘but why does she need that attention?’ Second, some self-harmers themselves justified public viewing of cuts and scars, and challenged negative interpretations of attention-seeking. An example of the latter strategy is seen in the data from Cherie in a later section of the article (Alternative discursive strategies). Despite these attempts to undermine the dualism, it was very resistant to challenge and a morally loaded public-private dualism ran right through our interviews and focus groups. To illustrate how the dualism played out in young people’s talk and to identify its effects, we present an analysis of discursive strategies. We discuss two data excerpts from young women. One of these interviewees has self-harmed; the other has not. After the first excerpt there is a break in the empirical material for a general discussion of the public-private dualism.

The discursive construction of a public-private dualism

This section shows how the dualistic construction of self-harm is accomplished and describes its effects. While our data are from research-contrived talk in interview and focus group discussion, we argue that such data provide insight into the routine discursive construction of the topic at hand. We start with an excerpt from an interview with Rosie, a university student who has not self-harmed, but has encountered self-harm in others.

Rosie: There’s been so much on TV about this self-harming. I don’t claim to know a great deal about that. I mean obviously it’s sort of supposed to be people who kind of internalise their problems and take it out on themselves to make it feel, they get some kind of release from it, so I mean we hear an awful a lot about that. I really don’t know that much about that.

Liz: No no

Rosie :I have encountered it at school but at school it was almost like it became a fashion it was, I mean you hear about self-harming being done in secret and people wearing you know long baggy clothes to conceal what they’ve done. People in my school would sit there openly with a rusty compass in the back of the classroom.

Liz: Seriously?

Rosie: Yes

Liz: And do what?

Rosie: And cut themselves. You know carve things into themselves. And it just became like a badge um.

Liz: And how were those people viewed in school? I mean

Rosie: For the people on the outside of that you weren’t involved it was kind of viewed with disdain. People thought it was attention-seeking behaviour and it’s quite difficult to look at it as anything other than attention-seeking behaviour when it’s been done in public like that [...] It tended to be more girls in fact I can’t think of a single lad who did do it, I think there were a couple but it was definitely a female thing.

Liz: Right and what sort of, what sort of girls were they, you know, was there a perspective on what they were like you know in schools people you know?

Rosie: They did tend to be like the more working class um that sounds really snobby I don’t mean it to um

Liz: God that’s fascinating isn’t it

Rosie: But the ones from you know more from the sort of council estates that kind of thing and they would, they tended to be um the ones who did, would be in like a group it wasn’t isolated they would be friends and they would see each other outside of school as well […] That’s the only time I’ve ever directly come across self-harm.

Liz: What if what if um one of you know your close friends at University you found that she was for example or he um was cutting themselves how do you think you’d feel about it?

Rosie: My girlfriend actually has got a bit of a history with this but doesn’t do it anymore. I think she cut herself once, and it’s just something that makes me feel powerless, ‘cause I don’t understand it where as I understand alcohol abuse a lot more.

Liz: Yes

Rosie: That’s the problem if you don’t understand something it’s very difficult to know how to help someone I think to get some out of it. To me it’s just an alien concept.

Liz: Yes and just so, yes you if you, what kind of reaction do you have though do you think of it as attention-seeking behaviour?

Rosie:Not with her it wasn’t no

Liz: No

Rosie: No because it was done in private and it wasn’t something that she was happy about or displaying or sort of wearing as a badge of honour or anything (Interview – North of England).

Willig (2003) prompts us to examine how the same discursive object is constructed in different ways. Rosie is, among other things, clearly contrasting public and private self-harm in this passage. It is worth noting that Rosie’s account does not emerge in an interactional vacuum. The interviewer (Liz) works to collaborate with her account, rendering some aspects as remarkable (e.g. ‘Seriously?’, ‘God that’s fascinating’). However, the interviewer’s interjections have not introduced new material. The connection between self-harm and social class, for example, is clearly introduced by Rosie without any specific prompting.

Rosie begins with reference to the discourse of self-harm as private self-directed distress, perhaps implying a degree of sympathy with this discourse but distancing herself from it by claiming to know nothing about it. She then goes on to show that she does know something about public self-harm. In connection with this she uses terms such as ‘badge’, ‘fashion’ and ‘carve’, using these terms to suggest a negative judgement of public displays of self-harm. This is cutting for public consumption, not for private release from distress (which is ‘concealed’ and ‘internalised’). When asked who the public cutters (or carvers) were, she clarifies that it was girls and in fact working class girls from the council estates who were in a friendship group. Following Willig (2003) again, we consider what is gained from constructing the discursive object in this particular way and what subject positions are offered by these constructions. Rosie positions her self-harming classmates as Other (De Beauvoir 1972 [1949]), and as lacking authenticity. She positions public acts of self-harm as not serious and as not deserving of sympathy. She identifies working class girls who engage in public self-harming as being together in a social group (of which she, herself, is not a part). She precludes any engagement with these girls. In a dichotomous relation to public cutting, she attempts to understand private self-harm and, ultimately, to sympathetically account for her girlfriend’s self-harm. She positions her girlfriend’s cutting as deserving sympathy and support and as being a genuine expression of distress. At this point we pause to consider the implications of the public-private moral dualism that is evident in Rosie’s interview and evident throughout our data. We then return to the data to consider possible challenges to the public-private dualism.

Discussion

When we consider the social importance of display, there is something of a puzzle here. Janet Finch introduces the concept of ‘display’ in relation to families. She writes:

By ‘displaying’ I mean to emphasize the fundamentally social nature of family practices, where the meaning of one’s actions has to be both conveyed to and understood by relevant others if those actions are to be effective as constituting ‘family’ practices (Finch 2007: 66).

As was noted in this article’s opening remarks, display could be thought to be especially relevant in youth. Young people in the West are generally meant to be conspicuous at least to each other. But in relation to self-harm it is important not to convey to others the signs of distress in order to prove that your distress is authentic. In suggesting an authentically distressed subject, we are drawing on an understanding of authenticity as fluid and intersubjective (Taylor 1991, Mendez 2008). Thus, the self-harming subject is constructed as potentially more or less authentic according to the extent to which their signs of distress are displayed to others.

In fact it is not feasible for ‘private’ self-harm to be wholly un-communicated. Arguably, self-harm often involves some form of display, whether via physical signs or via discussion with other self-harmers in support groups or on-line. Here lies the puzzle. Why do young people believe that only self-harm that is not physically displayed is authentic and suggests genuine distress? To suggest some possible answers, we need to consider the contemporary discursive context of mental health and illness.

While ‘serious’ mental illness with a diagnosis is usually stigmatised (Hayward and Bright 1997), it could also be seen as deserving sympathy and concern, because it causes suffering and is regarded as beyond the patient’s control. In contrast, lower level difficulties may well be seen as not so serious and as more within the control of the patient, therefore evoking less sympathy (see McPherson and Armstrong 2009). That people whose emotional distress is regarded as less serious may then be subject to a moral imperative to pull themselves together chimes with Foucault’s (1967)argument that definitions of ‘madness’ regulate morality. It is perhaps especially acute in relation to young people because the idea that youth is a time for emotional drama (Roen et al. 2008) sets up an expectation that symptoms of distress might be exaggerated.

The dualistic approach that the young research participants drew on resonates clearly with some clinical interpretations of self-harm. There are numerous studies which show pejorative judgements from clinical staff on ‘time-wasters’ who repeatedly present with self-inflicted cuts and overdoses (see, for example, Jeffrey 1979, Crawford et al. 2003, Friedman et al. 2006). Crawford et al. (2003) have specifically studied attitudes towards self-harming adolescents and there may well be a more widespread assumption among clinical staff that ‘time-wasters’ are likely to be young, given the association between youth and ‘drama’. We might conclude that the splitting of self-harmers into good and bad categories could relate in some way to this clinical culture. There are at least echoes of medicine’s general approach of categorising people according to the severity of their condition and treatability. It is also possible that stories of self-harming time-wasters have become common currency because they are ‘good stories’ (Carter 2008). However, it is equally credible to make sense of the well known pejorative judgements of self-harmers in Accident and Emergency departments, for example, as not so much as about the power of medicine to categorise people as about the influence of lay moral judgements on medical practice (Jeffery 1979).

This may be understood as a double hermeneutic process, whereby knowledge spirals in and out of lay and expert realms (Giddens 1993). One example of making a connection between lay and expert knowledge on health is Chandler’s (2008)discussion of the disdain for ‘attention-seeking’ self-harm with reference to Williams’s (1998) work on the individual moral imperative in late modernity for us to have healthy bodies. Chandler notes that self-harm transgresses this moral imperative in most people’s eyes, although she also notes that her own research and other studies have in fact shown people who self-harm tending to describe this behaviour as life-preserving and healing rather than as being associated with death or illness.

But why the public-private dualism? To address this question, let us work with the concepts of rationality, intelligibility and stigma. Rationality is important to the neo-liberal self as responsible and emotionally contained (Rose 1989). One way to understand participants’ disdain for public displays of self-harm would be to consider them as contravening our ideas of the responsible and rational self. Further, deliberately harming one’s own body is likely to be unintelligible. It does not typically make sense to others, or at least is hard for others to read. It is the very unintelligibility of self-harm that leads to its definition as irrational (Foucault 1967).

We need to consider the interplay between irrationality, unintelligibility, mental illness, and morality. In Greek, stigma initially referred to marks cut into the body to ‘expose something unusual and bad about the moral status of the signifier’ (Goffman 1968: 11). Here, the cut represents some kind of moral deficit, something shameful; something that one might sensibly want to hide. Given that mental illness is stigmatising, there is no surprise that intense emotional distress may draw some sympathy from others, but they are unlikely to want to rub up against it. They would probably prefer it to be kept private. Distress becomes a private shame and the cut is potentially a way of displaying that shame and forcing others to acknowledge one’s distress. And such public display of one’s own stigma is surely going to be misread by others, and not met with sympathy or understanding by many.

The gendered and classed construction of self-harm in the passage from Rosie above warrants some brief comment, although a full discussion is beyond the scope of this article. The gender profile of self-harm in the data excerpt above from Rosie’s interview may be stereotypical but is in fact a reasonably accurate impression, according to the epidemiological research, and therefore perhaps not surprising. There is also clearly an important cultural dimension to the association, however. Canetto’s (1997) research on the ‘gendered cultural scripts’ operating in relation to young people’s suicidal behaviour notes the common associations of ‘successful’ suicides with masculine decisiveness and ‘failed’ suicide attempts with manipulative femininity. Although Rosie is talking about behaviour which is not so life-threatening, we can see connections between the moral judgement of feminised suicide attempts described by Canetto (1997) and Rosie’s gendered construction of manipulative self-harm. Less clearly connected to the epidemiological evidence is the association by Rosie of self-harm with girls from working class backgrounds. We could perhaps usefully relate this association to regulatory class discourses which represent the working class through excess and overt display, while the middle classes are represented by associations with restraint and modesty (Skeggs 2004). However, a dedicated and sustained investigation of the relationship between young people, social class and self-harm is largely missing in published research to date, so we also note this as an important issue for exploration in future studies.

Alternative discursive strategies

At this point we return to our data, taking a discourse analytic approach to another specific passage. The data below move the argument on from the dualism discussed above and lead us to consider implications for practitioners in health and social care.

Chandler (2008) describes some of her research participants, who have personal experience of self-harm, clearly positioning themselves as having self-injured to get attention and justifying that this was necessary at the time (and not just done ‘to be cool’), although in all cases this behaviour was firmly in the past and (with the possible exception of one interviewee) was spoken of in generally negative terms or at least contrasted with more ‘genuine’ private or secret cutting. The interview excerpt below from Cherie confirms that the possibility of using public self-harming to draw attention may resonate with the actual experiences of some people who self-harm. Aspects of the young people’s discourse about public and private self-harm do in fact tell us something about the diverse social functions of self-harming. This excerpt from Cherie, who has self-harmed, is notable for its attempt to set out an alternative discourse on public self-harm. Cherie directly confronts the moral disdain of attention-seeking:

Cherie:Some people, I do know people who do it to attention-seek but they do it because people don’t [tails off]. Right I have a friend who does it and I know why she does it, she does it because people don’t understand how she feels and she puts on this act and she’s dead happy all the time but she’s not at all. And she’s got a lot of things going on at home, so she cuts herself so people ask her what’s wrong because it’s easier for that to happen rather than her actually going up to them and saying you know, I need to talk to you. Um, I know people who cut themselves to the point where they have to go into hospital, I know a girl who drinks bleach, just so that she has to go into hospital and that’s another attention fact. They actually need to go into hospital to feel loved and cared about because they feel like they are not getting it from anywhere else. And then there’s the people who say they are attention-seeking but they are really not and cutting is something, a lot of people are ashamed of so why would they, people who really have issues going on deep down, why would they want people to know they were cutting themselves because it’s not something, it’s not really, I hate using the word but it’s not really the normal thing to do, you are not supposed to hurt yourself. And a lot of people get this sort of psycho nametag because you harm yourself. […] Yeah because um, one of the people who do it so people ask them what’s wrong um, she was being beaten up at home by her dad, but nothing visible. So her way was that if I cut myself people are going to notice that there is something wrong. The problem is nobody noticed for a long time and it got out control to the point where it was just clear she was not coping at all. People do it for different reasons and I can’t stand people who criticise and say like, oh why do you self-harm, take up smoking, get a hobby or you know, cry for a while because sometimes, like I said before, that feeling doesn’t go away and crying and whatever else doesn’t help, so you’ve got to find some way of getting it out.

Cherie constructs self-harm as a legitimate strategy for coping with emotional difficulties. She refers in the middle of this passage to the idea of self-harm as a private method of self-care, but she also talks of self-harm as a means of connecting with others. She validates self-harm as a way of getting attention from others, for people who are legitimately distressed and find it hard to talk about what is wrong and therefore need alternative ways of seeking help and being loved and looked after by others. She is arguably making the irrational (publicly self-harming) self rational by reconstructing it as a legitimate call for help. She is constructing the ‘attention-seeking’ self-harmer as a reasonable individual making choices about how to cope with distress (Rose 1989).

She also talks about emotional build up and release, suggesting that one has to ‘find some way of getting it out’. This is psychodynamic discourse; the idea that emotions well up inside and one needs to find a way of letting them out. Just crying does not work, but self-harm might work. Cherie offers possibilities for self-harmers to be taken seriously without their reasons being judged and without the validity of their distress being evaluated. She closes down possibilities for judging and pathologising self-harmers. Self-harm is, however, not spoken about as something that is resolvable. Rather it is a kind of solution in itself. She closes down consideration of other coping strategies and undermines the value of crying and talking.

What becomes possible through this discursive framing of self-harm and of self-harmers is a stand-off between ‘us’ and ‘them’, where ‘we’ are the people who are suffering and are using self-harm as a legitimate coping strategy, and ‘they’ are the people who do not understand what ‘we’ are doing. In this context, alternative suggestions from ‘them’ can be read as criticism, not understanding, and can be rejected as annoying. Furthermore, any self-harming behaviour can be legitimated and defended as a valid expression of distress, without alternative ways of seeking help or making pain visible being considered. Within this framework of understanding, it might be possible to feel determined to use self-harm as a means of expressing and coping with emotional distress. It is possible to ‘not be able to stand people’ who try to suggest alternative coping mechanisms. This framing of self-harm, if taken to an extreme, might make it impossible to conceive of other coping mechanisms once self-harm has begun.

This analysis goes some way to extend the ideas put forward by Crouch and Wright (2004) and by Spandler (1996). In these previous studies, it was noted that a paradoxical situation was being set up, because of constructions of attention-seeking, whereby self-harmers did not want ‘to be thought of as attention-seeking’ but did acknowledge themselves to be ‘needing some attention from others’ (Crouch and Wright 2004: 196). Crouch and Wright noted that ‘participants wanted people to notice and care about them but hid their self-harm from others’ (Crouch and Wright 2004: 197). The present analysis, however, demonstrates how an alternative subject position may be set up as a way of dealing with these contradictions. Cherie’s talk, for instance, offers a subject position that is about defending self-harm and self-harmers against criticisms, effectively positioning self-harm as a viable and rational means of coping. Such an approach is consistent with other reports from those who self-harm (Cresswell 2005), even though it works against popular understandings of self-harm in terms of the public/private dichotomy suggested in much of the data presented in this article. On a general level, Cherie’s approach has echoes of the pro-anorexia movement, which also involves positive reframing of behaviour which is stigmatised and problematised. As in the ‘pro-ana’ website studied by Fox et al. (2005), there is an emphasis on the ‘problem’ behaviour as a symptom of underlying disturbance and as a legitimate sanctuary from emotional pain.

Conclusion

We conclude with some comments about the implications of our data and discussion for health and social care. Some working in the health and social care field have attempted to reject what they see as the dominant medical framing of self-harm and remove pejorative moral judgements, first by asserting the role of self-harm as coping with life rather than threatening it, and second by asserting the private nature of most self-harm. Although this challenge may have been necessary in care contexts with traditional formulaic responses, it does not take account of the reality that some self-harm is not intended to be wholly private but does seem to be communicative and appropriate responses are therefore needed. It is important for practitioners to acknowledge that self-harm may have a variety of social functions. It would be wrong to replace one orthodoxy (self-harm is attention-seeking so should be ignored) with another one (self-harm is a private coping strategy) when in fact the picture is complicated and the same behaviour can mean different things to different people at different times. So perhaps most important of all for practitioners is an acknowledgement that self-harm is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon and therefore it is useful to consider multiple ways of understanding self-harm. This is consistent with what is already known about self-harm having diverse functions (Skegg 2005).

Moral judgements about public self-harm are met by some of our research participants (and perhaps especially those who self-harmed) with the challenge to others to consider ‘why do they need attention?’ This may perhaps be a useful construction for practitioners in health and social care, as a respectful approach which does not stigmatise a particular behaviour. Cherie, in the passage above, explains why people take the extreme measures of self-harm so they can be ‘loved and cared about’ when they find it difficult to ask for help. She is effectively accepting that there is a communicative aspect in some self-harm and arguing that this should not be denigrated.

It is worth noting that there are also risks for practitioners in taking at face value the idea of self-harm as a way of communicating distress, as this could potentially be seen to reinforce the idea that self-harm is the defensible way to deal with distress, thus closing down alternative ways of coping. Here, work could usefully be done to examine what it is about constructions of self-harm that enables and supports self-harming behaviour, where the points of resistance are in discourses that frame self-harming as a (or perhaps the) valid way of coping with distress, and how alternative methods of coping with distress might become discursively possible.

While health and social care practitioners cannot wish away the discursive tension inherent in the public-private dualism in the construction of self-harm, there are opportunities to work creatively in relation to this discursive framing. One approach to consider is acknowledging this dualism in working with people who self-harm and making it explicit on the grounds that it will be around anyway. Crouch and Wright (2004) recommend using therapeutic groupwork with self-harmers. Using groupwork to make dualistic constructions explicit and to question them may be a sensible approach. If the dualism is left implicit, there is a risk that those who self-harm will compete for authenticity through inflicting more serious injuries and keeping them secret, as Crouch and Wright (2004) note.

Footnotes

The research project had a particular focus on sexual identity (see McDermott et al. 2008)

References

Canetto, S.S. (1997) Meanings of gender and suicidal behavior during adolescence, Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviour, 27, 4, 339–51.

Carter, B. (2008) ‘Good’ and ‘bad’ stories: decisive moments, ‘shock and awe’ and being moral, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 8, 1063–70.

Chandler, A. (2008) ‘Just’ a cry for help? Exploring the communicative aspects of self-harm and suicidal behaviour. Paper at Ethnographies of Suicide conference, Brunel University, 2–3 July.

Crawford, T., Geraghty, W., Street, K. and Simonoff, E. (2003) Staff knowledge and attitudes towards deliberate self-harm in adolescents, Journal of Adolescence, 26, 5, 619–29.

Cresswell, M. (2005) Self-harm ‘survivors’ and psychiatry in England, 1988–1996, Social Theory and Health, 3, 3, 259–285.

Crouch, W. and Wright, J. (2004) Deliberate self-harm at an adolescent unit: a qualitative investigation, Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 2, 185–204.

De Beauvoir, S. (1972 [1949]) The Second Sex. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Finch, J. (2007) Displaying families, Sociology, 41, 1, 65–81.

Foucault, M. (1967) Madness and civilization. London: Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1980) Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Fox, N., Ward, K. and O’Rourke, A. (2005) Pro-anorexia, weight-loss drugs and the internet: an ‘anti-recovery’ explanatory model of anorexia, Sociology of Health and Illness, 27, 7, 944–71.

Friedman, T., Newton, C., Coggan, C., Hooley, S., Patel, R., Pickard, M. and Mitchell, A. (2006) Predictors of A&E staff attitudes to self-harm patients who use self-laceration: influence of previous training and experience, Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60, 3, 273–77.

Giddens, A. (1993) New Rules of Sociological Method, Second edition. Cambridge: Polity.

Goffman, E, (1968) Stigma. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Hayward, P. and Bright, J.A. (1997) Stigma and mental illness: a review and critique, Journal of Mental Health, 6, 4, 345–54.

Hall, G.S. (1904) Adolescence: its psychology and its relation to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education (Vols. I & II). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hall, T. (2002) Seventeen forever: youth, adulthood and the young unemployed, Cardiff, School of Social Sciences Working Paper series no. 30.

Hawton, K., Rodham, K. with Evans, E. (2006) By Their Own Hand: Deliberate Self-harm and Suicidal Ideas in Adolescents. Jessica Kingsley: London.

Hollway, W. (1989) Subjectivity and Method in Psychology: Gender, Meaning and Science. London: Sage.

Hook, D. (2001) Discourse, knowledge, materiality, history – Foucault and discourse analysis, Theory and Psychology, 11, 4, 521–547.

Jeffery, R. (1979) Normal rubbish: deviant patients in casualty departments, Sociology of Health and Illness, 1, 1, 90–107.

McDermott, E., Roen, K. and Scourfield, J. (2008) Avoiding shame: young LGBT people, homophobia and self-destructive behaviour, Culture, Health and Sexuality, 10, 8, 815–29.

McPherson, S. and Armstrong, D. (2009) Negotiating ‘depression’ in primary care: a qualitative study, Social Science and Medicine, 69, 8, 1137–43.

Mendez, M.L. (2008) Middle class identities in a neoliberal age: tensions between contested authenticities, Sociological Review, 56, 2, 220–37.

Owens, D., Horrocks, J. and House, A. (2002) Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 3, 193–99.

Roen, K., Scourfield, J. and McDermott, E. (2008) Making sense of suicide: a discourse analysis of young people’s talk about suicidal subjecthood, Social Science and Medicine, 67, 12, 2089–97.

Rose, N. (1989) Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self. London: Routledge.

Skegg, K. (2005) Self-harm, Lancet, 366, 9495, 1471–83.

Skegg, K., Nada-Raja, S., Dickson, N., Paul, C. and Williams, S. (2003) Sexual orientation and self-harm in men and women, American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 3, 541–6.

Skeggs, B. (2004) Class, Self, Culture. Routledge, London.

Spandler, H. (1996) Who’s Hurting Who? Young Pople, Self Harm and Suicide. Manchester: 42nd Street.

Taylor, C. (1991) The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Warm, A., Murray, C. and Fox, J. (2003) Why do people self-harm?, Psychology, Health and Medicine, 8, 1, 71–9.

Wetherell, M. and Edley, N. (1999) Negotiating hegemonic masculinity: imaginary positions and psycho-discursive practices, Feminism & Psychology, 9, 3, 335–56.

Williams, S.J. (1998) Health as moral performance: ritual, transgression and taboo, Health, 2, 4, 435–57.

Willig, C. (2003) Discourse Analysis. In Smith, J. (ed.) Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Methods. London: Sage.

#qualitative research#sociology#sociology of health & illness#teenagers#self-harm#self-injury#self-perception#stigma#behavior#authenticity#cutting

0 notes

Video

youtube

Eric Wetherell - Sky (1975)

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes