#Dinka

Text

Dinka children by the fireside, South Sudan, 2013 - by Carol Beckwith (1945), American & Angela Fisher, Australian

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

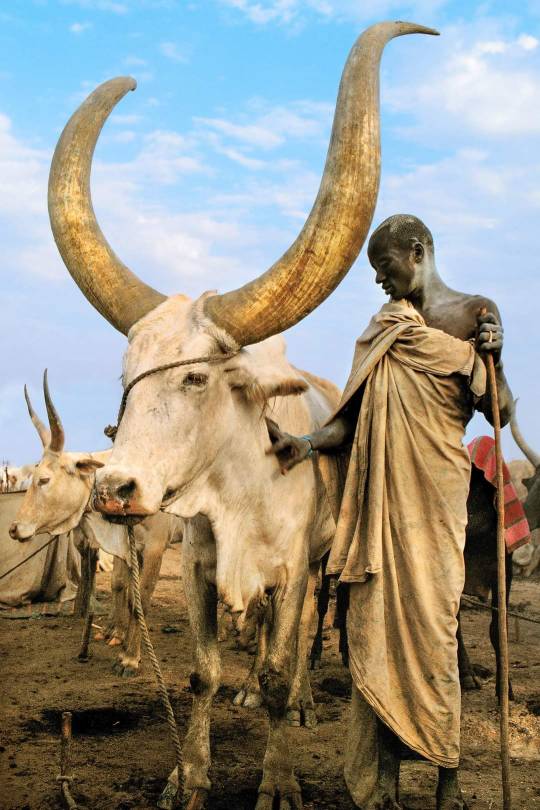

DINKA | SOUTH SUDAN

"At puberty a dinka male receives a namesake ox after which he is named. he believes that he and the animal are one being. from calfhood he trains its horns into beautiful lyre shapes, and emulates them with his arms as he walks."

More images, videos and information about the history, customs and traditions of the Dinka can be found on "Africa Online Museum"

www.africaonlinemuseum.org

https://instagram.com/nevzat.boyraz44

Image by African Ceremonies: Angela Fisher & Carol Beckwith

#Dinka#Africa#African#Africanhistory#BlackHistory#portrait#documentary#documentaryphotography#SouthSudan#Sudan#Spotify#türkiye#doğa#travel photography#travel destinations#travel#manzara#view#natural#europe#africa

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinka RT300

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dixie Kong as Link from "Link to the Past" (SNES) because Inka Dinka Doo

https://torvo-comics.wixsite.com/torvo

#donkey kong#dixie#kong#dixie kong#link#parody#monkey#primate#video games#snes#inka dinka doo#inka#dinka#doo#donkey kong country#donkey kong country 2#donkey kong country 3

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

NORTH & EAST AFRICAN RESOURCES

The Anthropological Masterlist is HERE.

North Africa is an African region that spans the northern part of the continent. North Africa shares many cultural and linguistic similarities with the Middle East.

BERBER ─ “The Berber, or Amazigh, people are an African people. They are native to North Africa.”

─ Berber Encyclopedia (in French)

─ Amazigh Culture (in French)

─ Berber Dictionary (in French)

GUANCHE ─ “The Guanche people are an African people. They are native to the Canary Islands.”

─ Guanche Information

─ Guanche History

KUSHITE ─ “The Kingdom of Kush was a Northeast African civilization that lived from 1070 B.C.E. to 550 C.E. They lived in modern-day northern Sudan and southern Egypt.”

─ Kushite Information

─ Kerma History

─ Meroitic Language

KABYLE ─ “The Kabyle people are an African people. They are native to northern Algeria.”

─ Kabyle History (in French)

East Africa is an African region that spans the eastern part of the continent. East Africa shares many cultural and linguistic similarities with the Middle East.

BAGANDA ─ “The Baganda, or Ganda, people are an African people. They are native to Buganda in Uganda.”

─ Baganda Culture

BANYARWANDA ─ “The Banyarwanda, or Kingdom of Rwanda, were an African people that lived from the 15th century C.E. to the 20th century C.E. They lived in modern-day Rwanda.”

─ Rwanda in the 20th Century

─ Genocide in Rwanda

DINKA ─ “The Dinka people are an African people. They are native to South Sudan.”

─ Dinka Culture

─ Dinka Language

─ Dinka Language Grammar

ETHIOPIAN ─ “The Ethiopian people are an African people that share the Ethiopian culture. They are native to Ethiopia.”

─ Ethiopian History

─ Afar Language

─ Ethiopian Music

KIPSIGIS ─ “The Kipsigis, or Kipsigiis, people are an African people. They are native to Kenya.”

─ Kipsigis Recordings

LOZI ─ “The Lozi, or Barotse, people are an African people. They are native to Barotseland in western Zambia.”

─ Barotseland Information

─ Lozi Language

LUGBARA ─ “The Lugbara people are an African people. They are native to the West Nile region in Uganda.”

─ Lugbara Culture

─ Sacrifice in Lugbara Culture

MAASAI ─ “The Maasai people are an African people. They are native to Kenya and northern Tanzania.”

─ Maasai Information

─ Maasai Culture

─ Maasai Language

MAKUA ─ “The Makua, or Makhuwa, people are an African people. They are native to northern Mozambique.”

─ Makua Culture

SHONA ─ “The Shona people are an African people. They are native to Zimbabwe.”

─ Shona History

─ Shona Dictionary

SWAHILI ─ “The Swahili, or Waswahili, people are an African people. They are native to the Swahili coast.”

─ Swahili Information

─ Swahili Culture

─ Swahili Dictionaries

VENDA ─ “The Venda people are an African people. They are native to the South African and Zimbabwean border.”

─ Venda Culture

─ Venda Culture

#resources#north african#east african#berber#kabyle#guanche#kushite#baganda#banyarwanda#dinka#ethiopian#kipsigis#lozi#lugbara#maasai#makua#shona#swahili#venda

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinka Kanjo SJ

owner: DarkMauli on PSN

Grotti Turismo Omaggio

owner: Masanaga__ on PSN

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://agothring.tumblr.com/post/622972857609224192

Hello, I’d like to submit a religious text I’ve written. Your page is about East Africa and its very important to the Dinka. Your page features many poems and songs of the Dinka so I believe it will be interesting and important to your followers. Thank you.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dinka are one of the largest ethnic groups South Sudan. The essential features of Dinka religion fall under three headings, which may be regarded as its three principal dimensions – belief (the main objects of traditional religious belief are God, the divinities, spirits and the ancestors), worship and morality.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 79: Tone and Intonation? Tone and Intonation!

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Episode 79: Tone and Intonation? Tone and Intonation!’. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Lauren: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Lauren Gawne.

Gretchen: I’m Gretchen McCulloch. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about the melodies of words. But first, our most recent bonus episode was a recording of our liveshow with Dr. Kirby Conrod about language and gender that we held as part of LingFest.

Lauren: Thanks to all the patrons who attended, asked excellent questions, and also helped support us by keeping the show ad-free.

Gretchen: To get access to this bonus episode and many, many other bonus episodes to listen to go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm.

[Music]

Lauren: Hey.

Gretchen: Hey.

Lauren: Hey?

Gretchen: Hey!

Lauren: Hey!

Gretchen: So, here’s one word, “hey,” and it’s got a bunch of different vibes depending on what pitch contour we’re using with it.

Lauren: We can use those pitch contours with a whole bunch of different words to give them a different spin. If we have a word like, “ice cream.”

Gretchen: “Ice cream.”

Lauren: Oh, very serious. Uh, “Ice cream?”

Gretchen: That’s a bit of a question. Ice cream…?

Lauren: Ice cream and what?

Gretchen: Ice cream and ice cream!

Lauren: Perfect choice. “Ice cream!”

Gretchen: Very excited ice cream.

Lauren: We’ve said the word “ice cream” with a whole bunch of different intonation that’s given it different meaning. That’s because we’re making use of the way that we can change the melody of words that we’re saying.

Gretchen: When we talk about the different kinds of pitches that words can have that change the meanings they have, I think it’s probably useful to clarify what we mean by “changing the pitches of the words” in this particular context. It’s more like playing a word on a different kind of melody, which might be a very simple melody – it might just be one or two notes – and that melody is relative to the highness and lowness, the pitch of the words that came before it. But it’s not an absolute melody because that’s just sort of the range my voice lives in most of the time.

Lauren: And different voices live in different ranges just like if we visit the woodwind section of a bunch of instruments, we’ve got small instruments like a piccolo or a big instrument like an oboe or a bassoon. They can all play exactly the same tune; they just play them at a different pitch.

Gretchen: If we’re thinking about something that’s making a pitch intonation – say something like question intonation, which is one of the easiest ones to think about because it’s got that nice question mark for us to grab onto – different people saying something with question intonation is sort of like playing the same song – you know, “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” or something – on different kinds of instruments. It’s all making that same melody of going down a bit and then up at the end.

Lauren: There’s a lot of different meaning that we associate socially with different pitches – so whether someone has a high voice or a low voice. We played around a lot with this in our episode on vocal folds and how we have different associations with different pitches for different genders. In our interview with Nicole Holliday, she talked about how African American English has different intonation to Standard American English and what that says about identity, but today we’re gonna look at more of the ways that we can use pitch and melody to change sentences or words in the way that they have meaning.

Gretchen: Right. Let’s start with the version of different pitch melodies that is the most accessible to English speakers, and that’s the one that operates on a whole phrase and changes that meaning in relatively predictable ways no matter what sort of phrase it applies to. We have our example from earlier, “Ice cream? Ice cream. Ice cream! Ice cream. Ice cream.”

Lauren: And in all of those cases, no matter how you say it, it still refers to the creamy, frozen desert.

Gretchen: Right. But when we add something like question intonation or if we add list intonation or exclamation mark intonation, those change the ways in which it’s interpreted in this very predictable way. If we add question intonation to lots of other words, they all sound question-y. You can have: “Ice cream? Cake? Pizza? Barbecue? Umbrella? Clarinet?”

Lauren: Oh, okay, that’s not a “What’s for dinner?” list.

Gretchen: “Om nom nom, clarinet.”

Lauren: They all end up being questions.

Gretchen: Right. And you can do this with longer phrases and sentences to – especially, there’s subtle differences in different kinds of questions.

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: I’m gonna say one sentence with two different versions of question intonation, and I want you to tell me what you think the meaning difference is.

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: Number One, “Can you bring cake or ice cream?”, and Number Two, “Can you bring CAKE or ice cream?”

Lauren: Okay, so the first one, I feel like it’s much more open to like, you just want some kind of desert situation. I might turn up with a trifle, and it’s probably okay.

Gretchen: “Can you bring cake or ice cream?” – yeah, that’s sort of like a yes-no question, “Can you do this?”

Lauren: Some kind of desert.

Gretchen: As a general category.

Lauren: Whereas with the other one, I really feel like my options to bring are cake or ice cream, and I have to choose one or the other.

Gretchen: Right, exactly. In that case, I’m asking a question about these two alternatives and getting you to pick one, and actually, if you were to bring both, maybe that’d be kind of weird because I’m actually gonna get someone else to bring the other one.

Lauren: Yeah, probably gonna hedge my bets and bring an ice cream cake though.

Gretchen: Ice cream cake is always acceptable.

Lauren: Exactly where you go up in the phrase can really change the effect that the intonation has on the sentence. Questions rise up towards the end, but that’s very different to another type of rising up which is a phrase specifically known as a “high-rising terminal” but which you may know as “uptalk” where that also goes up towards the end, but the point in the sentence at which it goes up is a little bit different. So, you can tell the difference between a question and uptalk.

Gretchen: I think this is particularly interesting because when it comes to writing people often use a question mark to indicate both types of intonation. So, if you’re saying something like, “Ice cream?” But I think most people can actually tell the difference. Can I say them both to you and see which one you think is which?

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Here’s Number One, “There’s some ice cream?” and Number Two, “There’s some ice cream?”

Lauren: That first one goes up and stays up earlier and stronger, which sounds much more like uptalk than a question to me. We use that to indicate that someone wants to continue saying something.

Gretchen: Then in the second one, that’s more of a question which actually goes down first and then up towards the end. That’s “There’s some ice cream?” and “There’s some ice cream?” where I’m deliberately going “ice cream” – just going straight up over going down versus up. There’s this difference here, even though we’re not very precise about writing these sorts of intonational contours in English. People tend to use a question mark for both, and it’s obvious from context. But it’s fascinating to me that we can actually hear the difference.

Lauren: When it comes to analysing the difference, sometimes linguists will literally draw a little up and down pitch contour over the top of a sentence to show that the question one does have that downward before upward movement.

Gretchen: I love these. I feel like they’re very old school.

Lauren: It’s quite old school. You know, they are somewhat subjective, but they do show you the difference between the two patterns.

Gretchen: I love this style. I think it’s really quite easy to read. You often see them in typewritten manuscripts because it’s a little bit hard to do digitally, but it’s sort of easy to just draw with a pen. I find it quite easy and intuitive to read. Unfortunately, it’s a little bit harder to do things like technical comparison with because you’re drawing this very analogue curve, and then you’re looking at another sentence and being like, “Okay, is that the exact same shape that this person drew? Or did this little dip – was that just like their hand got jogged or did they mean something by it?”

Lauren: Other systems involve using notation, like you might use “H” for the bit that’s high and “L” for the bit that’s low. I’ve seen other notation systems that use arrows as well to indicate those upward and downward movements in the melody.

Gretchen: Yeah, the H and L one I feel like is relatively intuitive, although when you start combining it, it can get quite complicated. I’ve also seen people use numbering systems where you number pitches from one to four. The problem with this for me is that some people prefer a version where “one” is low and “four” is high, and some systems do the exact opposite thing, so when I see pitch numbers, I never quite know what’s going on.

Lauren: Always worth checking what their transcription system is before getting into things is a thing I’ve learnt when it comes to number systems.

Gretchen: Absolutely. I think that pitch systems are something where they’ve been one of the hardest things for me to learn at a technical level because when it comes to something like, “Okay, here’s some sounds. We’re gonna produce them. We���re gonna transcribe them. We’re gonna write down a bunch of symbols for them,” that’s something that I was able to learn in a relatively concrete way. But pitch is this thing that’s overlaid on top of the individual sounds and applies to the whole syllable or to the whole word or the whole sentence and has taken me quite a while to be able to train my ear to hear rather than just perceiving the sentence as like, “This is a question,” or “This is angry,” or “This is curious,” or something like that.

Lauren: I think it takes practice to step away because it is something that is often used for that kind of emotional and stylistic effect, so it can be harder to step back and think about what’s actually being done with intonation versus other things that we use strategically to create emotion in the way that we speak.

Gretchen: I feel like I’m better at it now than I used to be. I’m still not as good as somebody who does this full time, but it is something you can improve at with practice, for sure.

Lauren: Absolutely. I think the more you realise just how much it is dependent on the specific language, it can help you think a little bit about what’s happening with intonation. A thing like having rising intonation at the end of a question where it goes up is not something that happens in all languages.

Gretchen: I mean, I was calling this “question” intonation, but does every language ask questions by doing this low and then high thing?

Lauren: A lot of languages do, but that doesn’t mean that it’s all languages do it. Hawaiian is a language that has falling question intonation, as an example.

Gretchen: This is the Indigenous language of Hawai’i?

Lauren: Yeah. And what’s really interesting is that the Hawaiian creole that has arisen because of the contact between Hawaiian and English has actually continued to use that falling question intonation instead of English rising question intonation.

Gretchen: Oh, that’s really neat. That’s something that’s gotten passed on in the creole as well.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Question intonation is easy to talk about, but there’re also other things that pitch is doing. I think one of my favourites is using pitch to indicate things like attitude. A word like “great” – you could say something like, “Great.”

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: “Great!”

Lauren: Oh, much better.

Gretchen: “Great…”

Lauren: Oh, no need to be sarcastic.

Gretchen: So, that’s “Great. Great! Great…” It’s sort of starting medium and dropping to low – “Great.” Enthusiasm with the pitch starting very high and ending low – “Great!” Or sarcasm which starts and ends low – “Great…”

Lauren: It just stays low.

Gretchen: I’m picturing a teenager very sulkily in the corner – “Great…”

Lauren: Same word. The intonation gives it very different meanings.

Gretchen: Absolutely.

Lauren: And a lot of those meanings are conveyed by the English writing system in traditional writing systems, and it’s part of what I love about how you analyse how people are playing with new internet grammar and using all kinds of different techniques with the writing system to try and capture some of that spoken vibe.

Gretchen: This is something that I talked about a lot in Because Internet, but there’s also a Tumblr post that I think very succinctly summarises it in which the first poster says, “Part of the New Internet Grammar: using question marks not to denote questions, but upturns in voice, so that a tentative statement gets a question mark but a flatly delivered question doesn’t.” And then someone comes along, and I think very tongue-in-cheek says, all lowercase, no punctuation –

Lauren: “why would you do this”.

Gretchen: The first person again, “It just seems right?” – question mark. I think we’re evolving more subtle ways of indicating intonation like this, including things like deadpan questions or tentative statements, but it’s something that’s kind of a work-in-progress in English, which is a nifty thing to keep observing.

Lauren: You can also use intonation for emphasis. So, where you chose to create a rise in the sentence can indicate that something is prominent.

Gretchen: Yeah. If you’re looking in the freezer or something, and you’re making a list of what’s in there, you might end up with “ice CREAM” and “ice CUBES” even though normally you would say them as “ice cream” and “ice cubes” because they’ve both got “ice” in it, you wanna stress the other part – the “cream” and the “cubes” – to differentiate between them a little bit more. But intonation isn’t the only way that languages can emphasise different parts of a sentence. I feel like I had to learn how to do this a bit differently when I was getting more comfortable speaking French because, in English, we have this strong tendency to use this pitch part and also loudness and things like that to emphasise certain words. If you’re in an ice cream place, and it’s kind of loud, you might emphasise like, “Can I get TWO SCOOPS of the CHOCOLATE ice cream in a CONE, please?” to make each of those parts more distinct. But I feel like French is a bit more likely to use word order in terms of which part you say first rather than saying particular parts in a more emphatic way. That hasn’t been as effective for me when I’m speaking French.

Lauren: Interesting. And it’s a good reminder that when you’re learning a language, you often don’t overtly get taught how to use intonation. It’s something that you pick up from listening experiments and talking to people and listening to people and trying to imitate them.

Gretchen: Absolutely. Sometimes, it’s easy to imitate in the sense that when people are doing mock versions of an accent, the intonation contours, the characteristic intonation contours, are some of the things that come really early. But I feel like it’s also worth noting that sometimes what’s a characteristic intonation contour – just sort of a default one in one language – might be something that carries an emotional meaning in another language. I guess you wanna be cautious when you’re reading someone’s intonation as hostile or as overly friendly that this might be a relatively baseline thing for them, and it’s not that people are secretly hating you.

Lauren: If someone’s language doesn’t have a rise at the end of a question, it might come across as a hostile question, but it’s actually just the way they’re used to asking questions.

Gretchen: Yeah, it’s something that’s worth keeping in mind.

Lauren: So far, we’ve looked at how we can use pitch to change the meanings of full phrases or sentences, but we can also use changes in pitch to change the meanings of specific words.

Gretchen: Right. This is less of “ice-cream-question-mark” versus “ice-cream-yay” or “ice-cream-sarcastic” and more like “ice cream” versus “doorknob” or something completely different.

Lauren: Or famously in Mandarin, the difference in tone creates a difference between the word “mother” and “horse” but also the words “hemp” and “scold,” which are all part of the four-tone system in Mandarin.

Gretchen: They’re all based on “ma” pronounced with different tones. You have the word for “mother” which is “mā.”

Lauren: That’s high level.

Gretchen: “Mā.” The word for “hemp” which is “má.”

Lauren: That’s a rising tone.

Gretchen: “Má.” The word for “horse” which is “mǎ.”

Lauren: That’s falling with a bit of a rise at the end.

Gretchen: “Mǎ.” And the word for “scold,” which is “mà.”

Lauren: Which is just directly falling.

Gretchen: “Mà.” There are four tones in Mandarin. For the particular syllable “ma,” each of them corresponds to a word. But you could have other syllables where there happens to be a gap, and in this particular tone combined with this particular syllable, there isn’t a word that corresponds to that gap, whereas you don’t have something like in English, “Oh, we just never say this word with question intonation. You can’t question this word. No one ever questions peanuts. They just don’t get questioned.”

Lauren: Because the tone is so integral to the meaning of the word, tone is often much more likely to be expressed in the writing system if a language does have a writing system.

Gretchen: Both the Mandarin-type thing where the tone changes the meaning of the word and the English-type thing where the tone affects the meaning of the whole phrase, they’re both drawing on a similar resource at the acoustic level in terms of how the pitch melody changes as you’re producing the thing. But because they have such different functions in terms of language, they get referred to by different names. The English one is “intonation,” and the Mandarin one is “tone.” These are both words that crop up sometimes used a bit more loosely, but in the technical linguistic sense, “tone” is when the meaning of the word itself changes, and “intonation” is when the broader meaning of the word as it fits into the phrase or into the discourse changes.

Lauren: As far as we know, every spoken language makes use of intonation. Tone is actually pretty prevalent. There’re some estimates that 60-70% of the world’s languages do have this word meaning-changing tone function to some extent; it’s just that a lot of these languages are those languages with really small populations that you hear less about, and they’re concentrated outside of the Indo-European family.

Gretchen: With the notable exception of Mandarin and other Chinese languages – all of which, I think, have tone – which are not small languages.

Lauren: There’re definitely many large languages like Vietnamese and Hmong as well as, you said, the Chinese languages that have tone that are national languages – very visible – but also many, many of the world’s smaller languages also have tone systems of some type or another.

Gretchen: But because all languages make use of intonation somehow, if you’re not already familiar with a tone language, and you’re trying to learn one, sometimes people draw on the intonation resources by writing Mandarin tones using question marks and exclamation marks and things like that as a cue to bridge you over to using it for tone purposes. This can be pretty effective at a learning level.

Lauren: Huh, yeah, I could see how that would be useful. So, for that second tone, which is rising, you could map that onto your understanding of question intonation, which is also rising.

Gretchen: Exactly. This can be, sometimes, a notation thing that people can use to take notes with and help remember how to pronounce it. I find, for me, I haven’t really tried to learn Chinese, but I’ve been exposed to enough of the same “ma” example that shows up in linguistics a lot that I can now hear it and reproduce it immediately after someone has produced it, but I have a hard time retaining it in my long-term memory which tone a particular word has just because this is not something that I’m in the habit of paying attention to. But people do learn tone languages in adulthood. It’s a thing that’s possible. I just haven’t put enough effort into it.

Lauren: Confessions.

Gretchen: Like, there’re a lot of languages. I’d like to learn them all, but you know, so many languages, so little time.

Lauren: Beyond using your English punctuation hack to correlate to different tones, there are a variety of ways of writing especially the Mandarin tone system – especially if you’re using a Roman orthography. Some of those have been taken up more than others across different systems.

Gretchen: I think the most common way that people write tones in Mandarin these days is just using accent marks or diacritics on the vowels. You can have the “mā” tone being written with a flatline above the vowel. And then you can have an upwards-pointing line and a downwards-pointing line, and something that points down and then up, to match the shape of the tones.

Lauren: I think it’s become a lot easier to use these diacritics above the vowel for the tone with modern computer systems. I’m very grateful that we have those to make that kind of writing system easier. But there have been some other fun proposals over the years as well.

Gretchen: I am particularly fond of a proposal not necessarily for its practical benefit but for its interesting-ness called “Gwoyeu Romatzyh” – hope I’m pronouncing that right. This is a romanisation system that’s based on, okay, what if we just spelled each of the tones differently using Roman letters.

Lauren: Okay, so you spell the vowel part, which is where we hear the tone, differently depending on what the tone is?

Gretchen: Yeah. For example, what if you doubled the vowel – you know, instead of “A,” you wrote “AA” – to indicate one variant of tone. Or what if you put a silent R, that would be in your variety of English, after some vowels to indicate another kind of tone. Or what if you changed – instead of writing “NG” you wrote “NQ” and that was another way of writing a tone. And you would know based on the spelling, “Actually, this is different tones.”

Lauren: I’ve definitely seen Q used at the end of words as a silent – it’s not a letter, it’s just indicating that it’s a particular kind of low or falling tone in other languages where it was before the magic of easy computer writing systems and people were typing thing up on typewriters. I didn’t realise that they’ve probably got that from this older Chinese system. How interesting.

Gretchen: This is a system that was invented by this very, very cool Chinese linguist in history named Zhao Yuanren, who’s my favourite guy.

Lauren: I know Zhao from another way of transcribing Chinese tones. I didn’t realise he’d come up with all these different ways. “Zhao numbers” are where you use a set of numbers to indicate tone. I like this one because it gives you a little bit of information about what’s happening with the acoustics. You have the numbers one to five – “one” being the lowest range in the melody that people are using and “five” being the highest. Because these Mandarin have contours and movement, so you’re falling tone is “51” because it’s going from the highest to the lowest point, your rising tone is “35” because it’s rising, but the rise is less than that full fall on the falling tone.

Gretchen: That’s a really elegant system because it can also work for other languages beyond just Mandarin. You could use it to describe, in principle, any tone system as long as it’s either flat or just doing one transition. I guess you could put three numbers beside each other if you wanted to do rising-falling-rising-again.

Lauren: Definitely a lot less opaque than the changing the way you spell the vowels in a word, which is probably why it stayed around a bit longer.

Gretchen: But also, not necessarily the most practical thing because typing numbers every time you type a vowel so you can indicate what tones it has might get kind of tedious.

Lauren: Especially because they are written superscript, which is often quite annoying to type.

Gretchen: Especially on computers. I just love that both of these systems are by the same guy, Zhao, who is also the guy that came up with the famous Chinese sentence that illustrates the necessity of writing tone in Chinese – he had some themes – which is the tongue-twister sentence that’s about the lion-eating poet in the stone den.

Lauren: Ooo, this is the one where it’s the same consonants and vowels and the only thing that changes is the tone, right?

Gretchen: Yeah, it’s just all versions of “shi” with different tones. If you write with without the tones, it’s just “shi shi shi shi shi,” and I’m not gonna do it justice by saying it out loud, but we are linking to a recording. It’s a really good demonstration of the necessity for one out of the many competing systems that he invented.

Lauren: It’s worth just saying that the Chinese writing system is such that because each word has its own character, the characters are all sufficiently different. They’re not based on the consonants and vowels. So, you memorise the character including its tone information. This is just something we’ve had to solve for more phonetic writing systems like English.

Gretchen: Right. And for trying to transliterate Chinese into Roman characters, which is sort of the project – he was involved with a lot of the early Romanisations in the 1930s and trying to figure out how to go about doing that. The neat thing about this poem is that it reads differently in different Chinese varieties. In Classical Chinese and in the writing system, it’s coherent. In Mandarin, it’s just four syllables because Mandarin’s just got four tones. But in Cantonese or Hokkien, it’s got 22 syllables or 15 syllables because these varieties have more tones.

Lauren: Another tone language that went through a Romanisation process but took a different approach to writing systems was Vietnamese, which has six tones. Vietnamese has also gone with this diacritic approach where you put little additional bits of information above or below the vowel, but it’s taken a very different approach to Mandarin.

Gretchen: I’ve seen Vietnamese on signs or on menus and things like that, and it’s really distinctive for having that little curved diacritic on the top of some of the vowels. It looks like a little backwards C or a hook. For example, in a word like “phở,” which is a delicious noodle dish, you see the curve at the top. What I didn’t realise until we were doing research for this episode was that this is actually from the interrogative question mark because Vietnamese had a lot of contact with French, which also uses question marks to indicate a rising intonation, and so this indicates a rising intonation because it was originally modelled after a question mark. They just made it really tiny and put it on the vowel.

Lauren: Huh!

Gretchen: Isn’t that cute?

Lauren: I’m used to diacritics that have a little rising bit because the intonation goes up, but I didn’t realise that this was directly inspired by the rising intonation of the question mark.

Gretchen: Yeah!

Lauren: That’s a good story.

Gretchen: You’ve worked on Tibetan languages, right? There’s tone in those?

Lauren: There is tone in Tibetan languages. Yolmo and Syuba, the languages I work with, have a two-tone system which only happens with some combinations of sounds. For sounds like /ma/ you can have “má” and “mà,” or a sound like /tə/, you can have “tó,” which is “rice,” and “tò,” which is “stone.” But there’re some sounds – like if you have a /kə/, there’s only ever a high tone. Like, “ká” is the word for “mouth.” If you have a sound like /gə/, you’ll only ever have a low tone. The tone isn’t for every combination of sounds. It is depending on the environment of the consonants that it’s hanging out with.

Gretchen: How do people go about writing that?

Lauren: The languages I work with have taken the Nepali writing system, which was designed for Indo-Aryan languages but maps pretty well to their sound system, and they often include a H to indicate low tone because that low tone is kind of breathy. They have a silent H there.

Gretchen: The “H” is not for “high”; it’s for the breathy low tone.

Lauren: Yeah. Just to be non-English about it. That word “stone” would be T-O-H in English orthography and using the H character in Devanagari as well.

Gretchen: Not that far off one of Zhao’s proposals, in fact.

Lauren: Not that far off one of Zhao’s proposals except that I think the Q was somewhat arbitrary, and the H does correlate with this kind of /h/ vibe to the vowel that the low tone brings. But for Tibetan languages that are written with the Tibetan script, what’s really interesting is the script doesn’t have anything about tone because it was in existence before the language developed tone. It’s something that can come about in a language.

Gretchen: So, the script is older than tone in the language itself.

Lauren: Yeah. And so, you tend to know what words have high or low tone because it’s that same kind of environment factor if it’s something that is more likely to have a high tone or a low tone. But it’s done with these very elaborate consonant clusters, which used to be pronounced and now aren’t and have become the tone system.

Gretchen: Sometimes, you get a silent letter like E that used to be pronounced, and at the time, it cued sound changes in the words. So, if you have something like “mat” versus “mate,” the E in “mate” would at one point have cued the vowel to be different. Now, even though that letter is silent, it still cues the same sort of sound changes that it used to.

Lauren: Except that it’s just doing it with tone in Tibetan. You have this nice little time capsule of how the language has changed sounds but still allows you to read tone into the language as well.

Gretchen: One of the ways of writing tones that I think is super interesting that we’ve talked about on the podcast a little bit before – just switching continents a little bit from Asia to Mexico – is in Chatino, which was in our interview with Hilaria Cruz, which we’ll link to, they’ve got either 14 or 11 tones depending on what you’re counting. In either case, that’s too much to use a diacritic accent mark-based system because that’s a lot of teeny-tiny accent marks. It’s also kind of a lot to use a numerical-based system because that’s more than nine or ten numerals to put at the end of your syllables. Instead, they use super script letters to indicate the different tones.

Lauren: That’s a good solution.

Gretchen: They have super script A, B, C and so on to indicate the different tones that are relevant for Chatino. Sometimes, they’re just written in all caps at the end of the word if the computer doesn’t support super scripts. These can convey the tones that they’re using.

Lauren: While we’re in the region, Zapotec is another language that has tone. It uses tone for something more grammatical. So far, we’ve been talking about how we change between words like “mother” and “horse,” or “stone” and “rice.” They’re completely different words that are unrelated to each other. In Zapotec, you can use three different tones to create differences in the grammar of the language.

Gretchen: The difference between “I will write” and “You will write” – there’s a suffix that’s added on to mean “I.” And then a high tone also gets added near the beginning of the word to go with that suffix which indicates I’m doing it as opposed to you’re doing it.

Lauren: This use of tone for grammatical things like tense or negation is also incredibly common across Central and Southern African languages as well.

Gretchen: There’s an example from Dinka, which is a language spoken in Sudan, where the tone is the thing that makes a difference between the meanings of the following four sentences. One is “I hate Acol,” which looks like a person’s name. Two is “Acol has been hated.”

Lauren: So, we’re moving who is doing the hating and making it a passive.

Gretchen: Right. Or “You hate Acol” – also yet another tone.

Lauren: Changing it from “I” to “you,” so changing the subject.

Gretchen: And then “Acol is hated.”

Lauren: Oh, the present passive as opposed to past passive. I feel really sorry for Acol.

Gretchen: Yeah, I dunno who Acol is. I don’t know why they keep showing up in these examples sentences and why people hate them so much, but grammatically it’s very interesting.

Lauren: Indeed. The only thing that’s changing is the tone on the verb “hate,” and that’s creating different forms of the verb.

Gretchen: It’s doing a lot of really interesting grammatical things in terms of changing important parts of the meaning. The use of tone for grammatical purposes, like changing it from “I do something” to “This has been done” or changing something from “I did it” to “You did it,” this gets lumped in together with tone in general – the use of tone to distinguish between one word and another word. I think that’s just because languages that use tone for grammatical purposes also use it to distinguish between individual words.

Lauren: There’s an incredibly wide range of ways in which especially languages like Dinka can use tone for a whole heap of different grammatical functions and word-changing functions.

Gretchen: That brings us to “Okay, if the majority of the world’s spoken languages have tone, and all the world’s spoken languages have intonation, what happens when you’re trying to do something like, say, ask a question, which often comes with a characteristic intonation, and also your language has individual tones on the individual words?”

Lauren: The answer is: it depends on how the tone system works, and how that comes together with intonation. Let’s look at some contrasting examples to simplify it.

Gretchen: You mean we’re not gonna run through every single language in the world and exactly how its tone and intonation systems work together?

Lauren: Well, I’ve only researched one. I’m gonna start with that one.

Gretchen: All right. Well, tell us about that one.

Lauren: This is one of those “I kind of messed something up and it turned out to be for the best” stories. We wanted to collect some tone data for Syuba, and so I asked some speakers to read out some word lists. I thought I was trying to be pretty good at preventing them from doing list intonation because that would get in the way of the tones. But for one or two speakers, we really didn’t do as good a job. It’s very hard when you’re recording long lists and it’s been long days. We had one or two speakers where there was this really strong list intonation.

Gretchen: In English, list intonation would be something like if you’re reading “Apples, bananas, oranges, ice cream, cake,” and each of those words is like, “There’s another word in this list.”

Lauren: Yes. You have this little rise at the end. That’s what I was getting in these recordings. But it turned out to be really useful because it showed us that intonation overruled tone in Syuba for speakers. That’s not a problem because there are only two tones. Not all words have a contrasting tone pair. Tone is not doing as much heavy work in meaning, and intonation can take over from it.

Gretchen: Sometimes, when you have a language with more tones, the tone and intonation interact with each other. Say you’re trying to put higher intonation at the end of a sentence for a question. That might just make every tone a little bit higher compared to what it would’ve been if it wasn’t a question. You can still hear that the tones are doing slightly different things.

Lauren: You see this with musical pitch as well. How a language is sung, the tone system might – again, with Syuba, speakers are very happy to just make the words fit into a melody because the melody of the music is more important – and not that there’re many songs about stones and rice, but if you were singing a song, you’d probably know if someone was talking about rice or talking about stones. You don’t need the tone to give you that information.

Gretchen: Ooo, can I talk about my favourite example of this?

Lauren: Sure.

Gretchen: This is a difference between Mandarin and Cantonese.

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: Both of which have tones, but Mandarin has four and Cantonese has six or nine depending on how you count. In Mandarin, it’s long been customary in music to not really pay attention to the relationship of tone and meaning, and context is just enough to fill it in.

Lauren: A bit like Yolmo and Syuba.

Gretchen: Yeah, whereas in Cantonese, there’s a long history in Cantonese opera, which is carried into Cantonese pop, of matching the tones to the notes.

Lauren: Again, that makes complete sense if that’s the priority your language has.

Gretchen: Right. This is largely relative, at least in pop songs. If the next note in the song is lower in pitch, then you want the word to be lower in tone. Or if it’s rising in pitch, you want it to be higher in tone – the next word – and just sort of continue along that melody. But this comes into problems if you’re trying to translate songs, and you’ve already got a melody, and you’ve already got a sense of what the word meaning you want is. If you are, for example – and this has happened – a Christian missionary going to China translating the meanings, the lyrics to hymns –

Lauren: Hymns that have existing melodies already that you probably don’t wanna change.

Gretchen: Nope, that you probably don’t wanna change, and you have a general vibe to the words already that you’re not super keen on changing either, you can end up with really funny things because if the tone mismatches, people interpret the words as something different. The example that I have is a hymn that was intending to say, “I am the sheep of the lord,” turned into something that sounded like, “I am a pig’s face.”

Lauren: Not quite the same vibe.

Gretchen: No. Because apparently “lord” and “pig” are the same syllables, the same consonant-vowel combination, but with different tones on them. So, this is a confusion that comes up maybe kind of a lot.

Lauren: A very good lesson for those working with tone languages doing translation.

Gretchen: Make sure to do cultural consultation if you wanna translate song lyrics.

Lauren: Throughout this whole episode, we’ve been talking about high and low tone and giving examples and mapping that onto ways of talking about sound that we’re used to from music and from melody, but it’s worth just saying very briefly that this is a cultural metaphor that we have when we’re talking about sounds.

Gretchen: Oh, yeah, I guess it is.

Lauren: Going back to our interview with Professor Suzy Styles about how we think about physically abstract things like sounds in terms of spatial realities and using highness and lowness as a metaphor. It’s not the only metaphor.

Gretchen: What other metaphors do different cultures use?

Lauren: There’s a metaphor in Farsi for pitch where you have “thin” or “thick.”

Gretchen: Can I guess which one’s thin and which one’s thick to see if it maps cross-culturally?

Lauren: Have a go.

Gretchen: All right. I’m gonna say that high notes are “thin” notes and low notes are “thick” notes?

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Excellent.

Lauren: But “thin” and “thick” is their default way of talking about it. There’re probably plenty of other metaphors cross-culturally. In fact, when I was learning to listen to tone in Syuba, I would talk to people about “high” and “low.” But one day we got ourselves into terrible confusion when I was working with one person because we were both using “high” and “low,” but I was using it in terms of musical pitch, and he was using it in terms of social status where what I thought of as “high” and “small” and “thin,” he was thinking of “small and thin and therefore socially inferior compared to someone who was big and round and rich.”

Gretchen: Sitting up on a big chair.

Lauren: Yes. So, low tone was very solid and social status and had authority, and we were using opposite high-low metaphors. I was using a spatial one; he was using a social status one. We ended up coming up with an agreement where we would just talk about whether it was the “rice” tone or the “stone” tone.

Gretchen: Perhaps something that doesn’t necessarily translate cross-culturally as much but definitely a practical solution at the time.

Lauren: Side-stepping any cultural metaphors that either of us were using.

Gretchen: That’s great.

Lauren: I like it because it explains this confusion that we both talked about earlier on about whether one was a high tone or a low tone. It depends on whether you’re thinking of one as solitary and small, tiny unit, and therefore high, or if you’re thinking about it as big and grand.

Gretchen: Sort of the baseline that other things build up from or something like that.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Going back to our metaphor of playing the same melody on a small instrument, like a piccolo, or a large instrument like an oboe, maybe we could also talk about “small” tone versus “large” tone. We could even see how many possible different tone metaphors we can come up with.

Lauren: I think there’s still a lot that we can learn across different languages for how they think and talk about tone and intonation.

Gretchen: We could try to make a list of how many different possible tone and intonation metaphors we can come up with.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, SoundCloud, YouTube, or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr. You can appreciate my list intonation right here. You can get fancy, aesthetic IPA charts, “Not Judging Your Grammar” stickers, and other Lingthusiasm merch at lingthusiasm.com/merch. I can be found as @GretchenAMcC on Twitter, my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com, and my book about internet language is called Because Internet.

Lauren: I tweet and blog as Superlinguo. Have you listened to all the Lingthusiasm episodes, and you wish there were more? You can get access to an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month plus our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now at patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Have you gotten really into linguistics, and you wish you had more people to talk with about it? Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans. Plus, all patrons help keep the show ad-free. Recent bonus topics include a language and gender Q&A with Dr. Kirby Conrod and the way science fiction depicts various futures for the English language. Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Gretchen: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Lauren: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#language#linguistics#lingthusiasm#transcripts#episode 79#podcasts#intonation#tone#uptalk#english#mandarin#cantonese#chinese#syuba#vietnamese#dinka#internet linguistics

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[ANF].

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinka Sugoi

and my MTL Brickade 6x6

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinka Bor's Traditional Culture Dance: A Cultural Tapestry of History and Resilience

Dinka Bor’s Traditional Culture Dance! The Dinka tribe is a Nilotic ethnic group native to South Sudan. The Dinka mostly live along the Nile, from Bor to Renk, in the region of Bahr el Ghazal, Upper Nile, and the Abyei Area of the Ngok Dinka in South Sudan.

The traditional culture dance of the Dinka Bor people is a mesmerizing and vibrant display of their rich heritage and profound connection to…

View On WordPress

#African History#Dinka#Dinka Bor&039;s Traditional Culture Dance#Dinka Dance#Dinka Traditional Culture Dance#east african history#North African History

0 notes