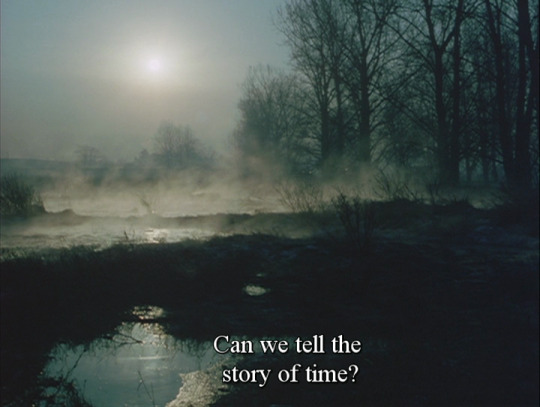

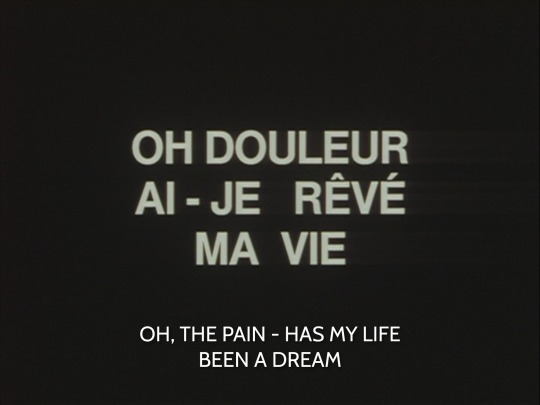

#Allemagne 90 neuf zero

Photo

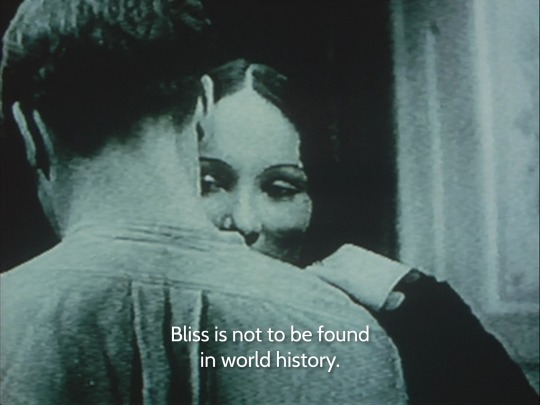

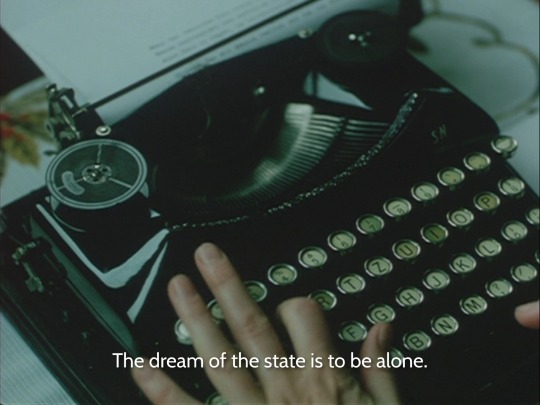

Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

#Allemagne 90 neuf zéro#Jean-Luc Godard#Godard#quote#time#1991#Jean luc godard#Allemagne 90 neuf zero#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#music#metaphor#story

869 notes

·

View notes

Text

...A Merry Godardian Christmas

Jean-Luc Godard

- Germany Year 90 Nine Zero

1991

#jean luc godard#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro#Allemagne année 90 neuf zero#christmas#merry christmas

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

ゴダールの新ドイツ零年-レミー・コーション最後の冒険

広瀬プロダクション

監督:ジャン=リュック・ゴダール/出演:エディ・コンスタンティーヌ、ハンス・ツィッシュラー ほか

#ALLEMAGNE ANNEE 90 NEUF ZERO#Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro#ゴダールの新ドイツ零年-レミー・コーション最後の冒険#新ドイツ零年#JEAN-LUC GODARD#jean luc godard#ジャン=リュック・ゴダール#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

8 notes

·

View notes

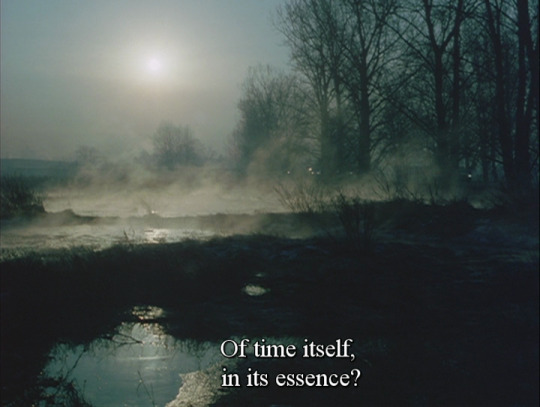

Photo

Jean-Luc Godard - Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991)

922 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Soldes : les "déconsommateurs" contre-attaquent

Soldes, Noël, "Black Friday"... les initiatives visant à faire prendre conscience des conséquences environnementales de ces kermesses de la surconsommation se multiplient. Avec un succès croissant, dû aussi à la perception d'une baisse du pouvoir d'achat.

Il était 8 heures du matin, ce mercredi 9 janvier aux Galeries Lafayette (Paris), quand la secrétaire d'État à l'Économie, Agnès Pannier-Runacher, a lancé les premiers soldes de 2019. Un événement très attendu par les commerçants après huit semaines de mobilisation des "Gilets Jaunes", dont le mouvement a pesé sur l'activité des commerces tous les samedi depuis le 17 novembre, date de départ de "l'Acte I" de cette protestation protéiforme. Ce mercredi 9 janvier, des grappes de dizaines de consommateurs avides de bonnes affaires ont donc pu s'éparpiller dans les rayons du grand magasin, pour profiter de l'un des grands rendez-vous annuel consacré à la consommation : les soldes d'hiver.

D'une manière très rapprochée, cette kermesse succède à deux autres : Noël, ainsi que le "Black Friday", le dernier vendredi de novembre, journée de rabais issue de la culture anglo-saxonne et, depuis quelques années, pratiquée aussi en France. Des moments importants pour les commerçants, puisqu'ils leur permettent de multiplier leurs chiffres de ventes, mais, d'autre part, de plus en plus décriés par les défenseurs de l'environnement. Ces derniers dénoncent les effets catastrophiques de ce type de consommation massive, souvent déconnectée des besoins réels, en termes d'épuisement des ressources comme de production de déchets.

3,5 tonnes de matières premières pour un téléviseur à écran plat

Selon une étude publiée en 2009 par l'Insee, le volume annuel de consommation par Français a en effet été multiplié par trois depuis 1960. L'élévation du niveau de vie, l'augmentation du temps libre, l'arrivée des produits low-cost et du commerce en ligne expliquent en partie cette tendance. Or, selon une étude publiée en septembre par l'Ademe sur le poids environnemental de 45 biens aujourd'hui plébiscités par les consommateurs, la production d'un seul téléviseur écran plat 55 pouces requiert quelque 3,5 tonnes de matières premières. Une simple robe en coton peut atteindre les 100 kg de matières, avec 43 kg d'émissions de CO2 associées à sa fabrication. 30% des articles réexpédiés par les clients déçus d'Amazon Allemagne finissent à la poubelle, a révélé une enquête réalisée en juin par la télévision publique allemande (ZDF) et le magazine économique WirtschaftWoche, la vérification de l'état du produit et le reconditionnement étant jugés trop coûteux.

Selon le Global Footprint Network, qui dans ses calculs tient compte également de la production de services (dont la consommation croît en France aux dépens des biens matériels), le "jour mondial du dépassement" tombe ainsi désormais le 1er août. Au rythme de consommation français, cette date, qui marque le moment ou l'humanité a consommé l'ensemble des ressources que la planète peut régénérer en un an, serait même anticipé au 5 mai. Et selon l'ONU, des 9 milliards de tonnes de plastique produites au monde depuis 1950, seulement 9% ont été recyclées : 12% ont été incinérées, alors que le reste est fini dans les décharges, les océans ou les canalisations.

Le succès des initiatives pour une consommation durable

Afin de promouvoir la prise de conscience de ces enjeux, les appels à la déconsommation se sont donc multipliés en France l'an dernier. Dès le début de l'année, l'association Zero Waste France a lancé le défi "Rien de neuf", demandant aux participants de s'engager à acheter le moins possible d'objets neufs et à privilégier des alternatives telles que la réparation, l'achat d'occasion, le don, la location, la mutualisation, etc. En novembre, le WWF France a lancé l'application "We Act for Good"(WAG), visant à accompagner les citoyens souhaitant changer de comportement en matière d'alimentation, production de déchets, mobilité et énergie. À l'arrivée de Noël, elle a même intégré des conseils particuliers en matière de décoration et de cadeaux, misant sur la créativité et le "fait maison".

Lors du Black Friday, le réseau d'entreprises de l'économie sociale et solidaire Envie a amplifié une initiative déjà lancée l'année précédente : le Green Friday, qui a réuni une centaine de marques et d'enseignes engagées à ne pas faire de réductions le dernier vendredi de novembre et à reverser 15% de leur chiffre d'affaire de la journée à une association promouvant la consommation durable. La toute nouvelle plateforme au service du développement durable Think2030, qui réunit une centaine d'experts et plaide pour une réduction de 80% des ressources consommées par chaque Européen, a profité de la même occasion pour adresser un appel aux femmes et hommes politiques, afin que la consommation durable devienne une priorité des élections du Parlement de l'Union européenne programmées pour 2019.

Bien qu'encore minoritaires, ces initiatives semblent rencontrer un succès croissant auprès des consommateurs. Sur Facebook, 17.113 personnes aiment la page Le Green Friday (marque déposée par Envie). WAG a déjà été téléchargée 200.000 fois selon le WWF, qui compte également 700.000 souscriptions aux "passages à l'action" proposés par l'appli. 15.000 personnes ont adhéré au défi Rien de neuf, qui en 2019 veut passer à l'échelle, en réunissant 100.000 participants et en proposant un outil leur permettant de mesurer la quantité de matières premières qu'ils ont économisées. Plus de 9.000 personnes ont déjà adhéré.

Un déclin "structurel" et "sociétal"

La tendance à une consommation plus responsable est d'ailleurs confirmée par les résultats du commerce. Au premier semestre 2018, les volumes de ventes de produits d'alimentation et d'entretien ont globalement baissé de 1,2 %, selon la société d'études Information Resources Incorporated (IRI) : le plus fort recul enregistré depuis la crise de 2008. Cette chute globale s'accompagne d'une hausse de la valeur du marché des produits de grande consommation de 0,7 %, en cachant ainsi un changement dans les choix d'achat favorisant la qualité, souligne l'IRI. Le bio, lui, affiche d'ailleurs depuis plusieurs années une croissance supérieure à 15%. Et selon l'Observatoire E. Leclerc des nouvelles consommations, même Noël n'a pas fait exception: 21% des personnes interrogées ont affirmé choisir des produits alimentaires respectueux de l'environnement et 41% des cadeaux éthiques.

Début décembre, l'Institut français de la mode (IFM) prévoyait pour sa part que la consommation de textile et d'habillement en France terminerait l'année 2018 en recul de 2,9% : l'un des pires résultats depuis 10 ans. Sur l'ensemble de la décennie, les achats ont baissé, en valeur comme en volume, de 10%. Et le scénario d'un rebond est "exclu", le déclin à l'œuvre depuis dix ans étant "structurel" et "sociétal", selon l'IFM, cité par Le Monde. Malgré la multiplication des promotions, les enseignes peinent en effet à écouler leurs collections. En 2018, des 44% des Français qui selon l'IFM ont acheté moins de vêtements, 40 % assurent l'avoir fait pour "acheter mieux", par "souci éthique", militantisme "écologique" ou pour "désencombrer leurs stocks". 90 % des consommateurs disent par ailleurs souhaiter "plus de transparence" sur les prix des vêtements et leur mode de fabrication. Seulement le luxe et les chaînes à bas prix semblent échapper au danger. Ainsi que "la vente d'habillement de seconde main, aujourd'hui évaluée à 1 milliard d'euros", selon l'IFM.

Le "bobo parisien" plutôt dans l'hyper-consommation

Le phénomène cache néanmoins aussi des ambiguïtés. Le sentiment d'une baisse du pouvoir achat joue en effet aussi un rôle très important dans la déconsommation à l'oeuvre : la majorité des Français ayant acheté moins de vêtements en 2018 disent y avoir été obligés faute de budget. 34% des répondants à l'enquête de l'Observatoire E.Leclerc des nouvelles consommations ont dit ne pas avoir les moyens financiers de réaliser tous leurs souhaits pour Noël, alors que 46 % étaient prêts à remplacer des produits emblématiques des fêtes (champagnes, foie gras...) par des alternatives moins chères. Si de la moitié des Français qui, selon une étude Rakuten-OpinionWay de décembre, ont déjà revendu un cadeau de Noël ou envisagé de le faire cette année, 23% disent préférer le revendre plutôt que le jeter, 21% affirment aussi vouloir ainsi se permettre ce qui leur fait vraiment plaisir.

Au contraire, le célèbre "bobo parisien" (ou "jeune urbain créatif": spécialiste du marketing, architecte, designer, professionnel de la culture et des médias, etc.), qui pourtant pense intégrer plus que la moyenne la préoccupation environnementale dans ses comportements d'achat (75 % des personnes interrogées), et ne se reconnaît pas dans le modèle de consommation de masse (57,9 %), est "dans une forme d'hyperconsommation tournée vers l'être plutôt que l'avoir", selon une étude de l'Observatoire société et consommation (L'ObSoCo), publiée le 4 décembre 2018 et citée par Le Monde. Impliqué dans le "fait maison", il fréquente pourtant des fast-food plus que la moyenne des Français (58 % contre 40 %) et se rend moins que la moyenne dans de marchés paysans ou de producteurs. 65,2% de ces "bobos parisiens" aiment aussi faire les soldes.

La Tribune

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Molly Nesbit Chases the Big Ideas

Cover of Molly Nesbit’s new book of essays (all photos courtesy of Inventory Press)

What’s the big idea?

In the field of intellectual history, that question usually leads to the examination of notions, propositions, theories, and arguments that have spurred the development of human civilization: its cultures, societies, beliefs, modes of communication, systems of administration, and assorted institutions. Written language, Buddha’s path to enlightenment, Plato’s ideal forms, Copernicus’s heliocentrism, Renaissance art’s illusionism, Shakespeare’s psychological insight, Hegel’s concept of history, Marx’s class struggle, Freud’s unconscious mind, Abstract-Expressionism’s angst, the birth of rock’n’roll, the death of God, the death of painting, the death of Elvis, the post-Cold War “end of history,” and Homer Simpson’s resonant, all-encompassing “D’oh!” — such events and products of the human imagination are all grist for the intellectual-history specialist’s idea-grinding mill.

Molly Nesbit, a professor in the art department at Vassar College, in Poughkeepsie, New York, is interested in what she referred to in a recent interview at her home in Manhattan as “the genealogy of ideas.” Reflecting that interest, in her new book, Midnight: The Tempest Essays (Inventory Press), she offers a selection of her art-centered essays, which were originally published in journals or exhibition catalogs between 1986 and the early 2000s. In them, what she’s up to is not conventional art history, but rather an exercise in recognizing certain dots (some big and others smaller and more subtle) on the time-map of art’s generative ideas and then connecting them — at times more purposefully and, sometimes, not.

Nesbit’s approach can feel scientific and a bit free-associative at the same time. Although she is rooted in the academy, her texts suggest a desire to break away from familiar, academic-writing models. The essays she has written combine the spirit of natural-history research — turning over rocks in search of clues — with that of poetry, for which a little ambiguity is something to savor, not proscribe.

Nesbit earned an undergraduate degree at Vassar and later continued her studies at Yale. At Vassar, she has taught courses focusing on various aspects of 20th-century art. She has written a book about the French photographer Eugène Atget and in 2013, her first collection of essays, Pragmatism in the History of Art, was published. Since 2002, with the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and the artist Rirkrit Tiravanjia, she has helped oversee Utopia Station, an ongoing, multifaceted project involving exhibitions, publications, and other activities.

Nesbit’s book reproduces a photo of Marcel Duchamp’s Coffee Mill, 1911, a drawing that is now in the collection of the Tate museums, London.

As the late-afternoon light began to fade in Nesbit’s book-strewn sitting room, she told me that the thinking that informs her approach “comes primarily from a set of developments that took place in art history in Europe and the United States in the 1970s and 1980s.” She was referring, of course, to trends associated with structuralism and later critical-analytical tendencies, which, broadly speaking, can be found in the general hopper marked “postmodernism,” along with post-structuralism and deconstruction.

However, Nesbit said that she would prefer not to use “postmodernist” to describe the overlapping currents of thought that inform the observations and analyses in her essays. Stepping back, she proposed, “Let’s just call it all ‘that broad way of thinking’” that many academics, intellectuals, and artists employ today, some with more self-awareness than others.

She explained that she is interested in how “art historians can use philosophical questions as starting points for their work,” and especially how “sustainable aesthetics,” as she put it, could be developed and practiced as an approach “that is integrated into the wider world, not separated from it, like modernism’s, which is critical but separated.”

“What Was An Author?” is an essay in the new book that looks at the meanings of “author” and “authorship” in the evolving context, since the late 1800s, of French law. Over time, it variously defined who or what constituted the author of an idea or a specific work vis-à-vis its applicable copyright protections and advancing media technology.

Nesbit points out that, by 1967, the French literary theorist Roland Barthes was signaling the “death of the author,” only to be followed by Michel Foucault’s declaration of the “author-function,” which effectively sent the visionary author packing. The “author-function,” Foucault wrote, “is tied to the legal and institutional systems that circumscribe, determine, and articulate the realm of discourse,” adding that “it does not refer, purely and simply, to an actual individual insofar as it simultaneously gives rise to a variety of egos and to a series of subjective positions that individuals of any class may come to occupy.”

In “The Copy,” Nesbit’s research about the sources of some of Marcel Duchamp’s “readymades” — the appropriated, quotidian objects he presented as works of art — is especially interesting; she links his drawings of such items and his seminal appropriationist gestures, which spawned legions of imitators, to 19th-century French drawing-instruction manuals filled with model trapezoids, curves, and other shapes, and sample images of manufactured objects in which such forms were visible.

From Nesbit’s book, pages from a French instructional volume about drawing, published in 1887; such images, she argues, influenced the modern artist Marcel Duchamp.

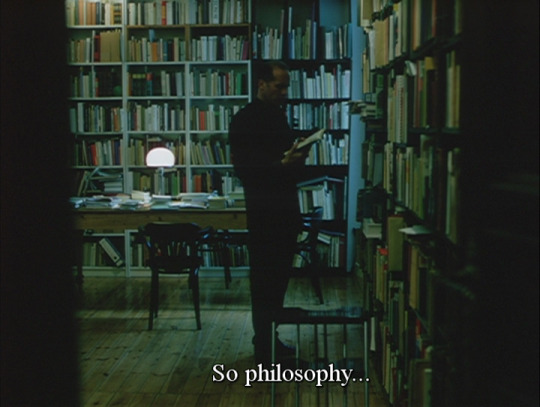

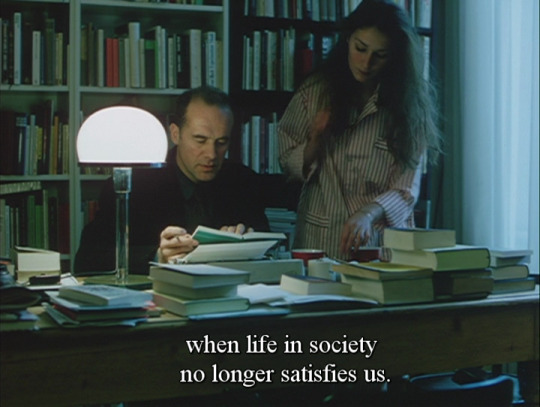

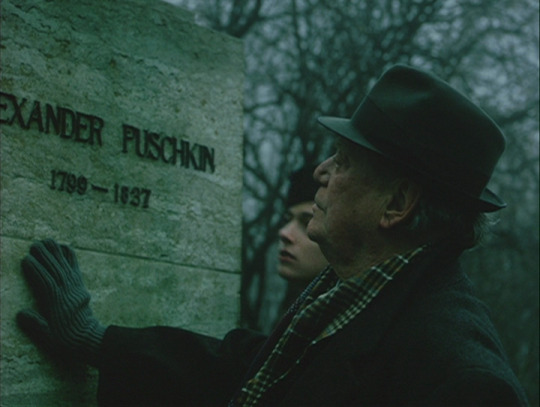

Elsewhere, Nesbit focuses on the film director Jean-Luc Godard’s “extreme techniques of montage that became his way of giving life itself, reality, a form.” He used it, she writes, “to break the rule of show-and-tell” that had typified so much of literature and the cinema’s approach to historical narratives. She examines Godard’s 1991 film Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro (Germany Year 90 Nine Zero), which was made after the Cold War’s end and looked back at German history. In it, she notes, Godard attempted to find “as many ways as he could to lay out the contradictions between past and present so that memory should never again grow cold and opaque.” She observes, “All futures sleep with their pasts at the risk of waking up alongside them.”

One of Nesbit’s essays looks at some of the definitive pomo artists who came to prominence in New York during the hype-driven 1980s — among them: Cindy Sherman, David Salle, Sherrie Levine. Overlooked in her discussion of Sherman is the recognition that her dressing-up, role-playing, selfie-photo schtick was already old when she revved it up in the late 1970s, and that, for some time, such pioneering feminist artists as Martha Wilson, Martha Rosler, Suzy Lake and others had already been examining women’s society-defined roles and images through photographic, performance-based artistic projects. Here, an air of veneration for Sherman, Salle and Levine’s offerings seems misplaced.

In an essay on certain postmodernist artists who came to prominence in the 1980s, Nesbit’s book reproduces Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Still #6” (1977).

As for Levine, in particular, how can anyone revisit her supposedly subversive appropriation, in 1981, of Walker Evans’ iconic photographs of poor, Depression-era tenant farm families (which had illustrated James Agee’s classic 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men) without calling attention to the paucity of talent and intellectual cowardice such a gesture represented? (For those unfamiliar with Levine’s banal exercise in pomo provocation, it consisted of her exact photographic copies of Evans’ original, black-and-white photographic prints, whose images she then exhibited and called her own. Oh, what a frisson of transgression it was supposed to have delivered, denying a real artist the “heroic” authorship of his own work and vision!)

With such subjects in mind, it’s unfortunate that Nesbit looks only at artists in the center of the art market’s mainstream (Gabriel Orozco, Gerhard Richter, and Matthew Barney turn up in these pages, too), for it could be exciting to see her apply her formidable observational skills to some truly original visionaries. After all, she quotes Duchamp’s often-cited observation, made in 1961: “The great artist of tomorrow will go underground.” Looking back, was pomo’s revered Saint Marcel on to something?

Looking back at the 1980s, Nesbit cites Sherrie Levine, who in 1981 made exact photographic copies of the iconic photos of Depression-era tenant farmers Walker Evans shot in the 1930s, thereby denying or negating his authorship of his own, original works.

More satisfying is the book’s last, long essay, “The Port of Calls,” which was first published in the catalog of Documenta 11, in Kassel, Germany, in 2002. It looks at New York in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 2001, not really making a graspable argument but instead floating through a mist of ideas and observations about utopia; destruction; art’s expressive potential; Duchamp on the risks of becoming a “successful” artist; Tiravanija’s audience-participation performance art; the big money that coursed through the mainstream art market of the 1990s; the architect Rem Koolhaas’s take on Manhattan’s buildings; and John Cage’s delicious, Zen-inspired contention that nothing could be regarded as something. As thought pieces go, “The Port of Calls” is all waves of intriguing, sometimes curious ideas gently washing up on a now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t, unknown shore.

“I’m interested in how ideas function in the world, in questions of practice, not just theory,” Nesbit told me. “I’m not interested in theory per se, but rather in thinking.” She added, “I’m interested in how we bring the past forward into the present for its wisdom. I work in the realities of the past. A lot of the past is still alive.”

With such concerns in mind, she explained, when she sat down to compose her essays, she asked herself, “With what kind of voice is it possible to write history” — imaginatively, that is — “without it turning into fiction?” As Midnight: The Tempest Essays shows, when she is in her stride, she can and does find the writing voice she is looking for — and it is no mere echo of a soulless, Foucaultian “author-function.”

Ultimately, using it to investigate the disparate range of subjects she considers here turns out to be her own big — and not such a bad — idea.

Midnight: The Tempest Essays (2017) is published by Inventory Press and is available from Amazon and other online booksellers.

The post Molly Nesbit Chases the Big Ideas appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2rCN9Ga

via IFTTT

0 notes

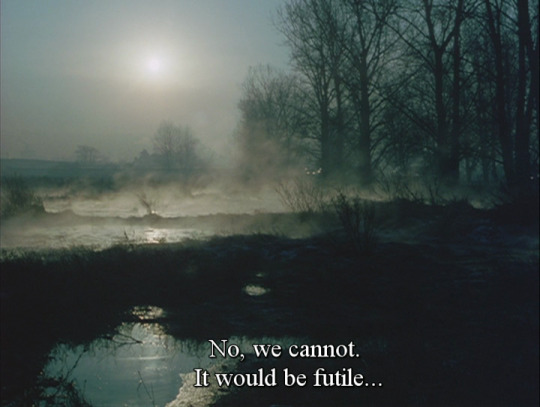

Photo

Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

#Allemagne 90 neuf zéro#Allemagne 90 neuf zero#Jean-Luc Godard#Godard#quote#philosophy#society#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#1991#life#think

835 notes

·

View notes

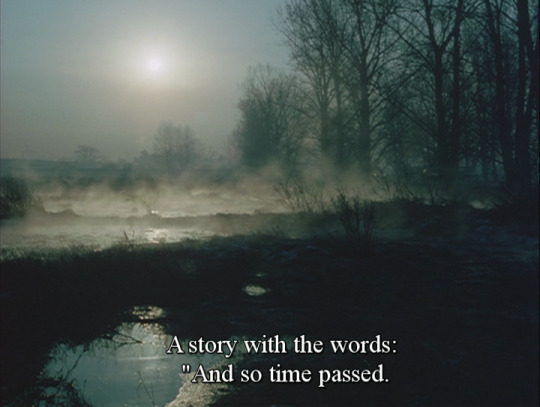

Photo

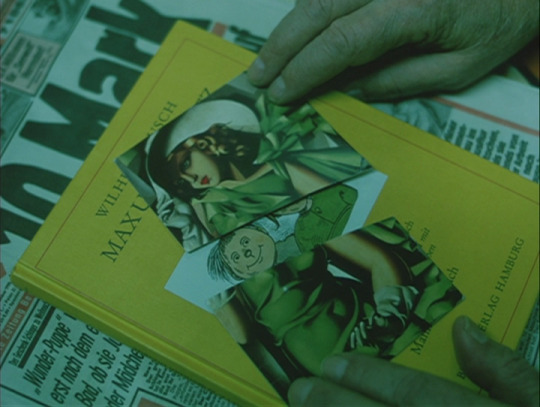

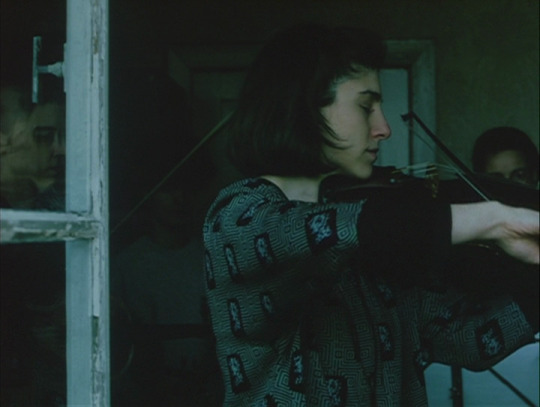

Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

#films watched in 2022#Allemagne 90 neuf zéro#Jean-Luc Godard#godard#siete#jean luc godard#Allemagne 90 neuf zero#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#Eddie Constantine#Hanns Zischler#Claudia Michelsen#Nathalie Kadem#drama#camera#back#loneliness#literature#book#books#music#violin#1991#hands#sculpture#bar

772 notes

·

View notes

Photo

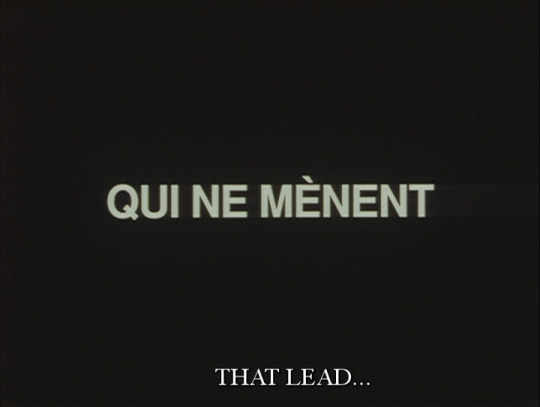

Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

#Allemagne 90 neuf zéro#Jean-Luc Godard#Godard#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#jean luc godard#quote#1991#philosophy#Allemagne 90 neuf zero

404 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

#Allemagne 90 neuf zéro#Jean-Luc Godard#Godard#Eddie Constantine#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#Allemagne 90 neuf zero#jean luc godard#quote#change#cahnges#waiting#1991

498 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

#Allemagne 90 neuf zéro#Jean-Luc Godard#Godard#1991#Allemagne 90 neuf zero#jean luc godard#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#Eddie Constantine#Hanns Zischler#Claudia Michelsen#back#drama#loneliness#faceless#beer#german#drink

215 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Films watched in 2022.

Top 10 August.

1. Visita ou Memórias e Confissões (Manoel de Oliveira, 1982)

2. Woman on the Run (Norman Foster, 1950)

3. Colegas (Eloy de la Iglesia, 1982)

4. Anticipation of the Night (Stan Brakhage, 1958)

5. Rien à foutre (Julie Lecoustre & Emmanuel Marre, 2021)

6. Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

7. The Driller Killer (Abel Ferrara, 1979)

8. Outside Noise (Ted Fendt, 2021)

9. Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935)

10. Lady Lazarus (Sandra Lahire, 1991)

(My list on Letterboxd -click here-)

#films watched in 2022#top 10#top 5#film#cinema#faces#Visita ou Memórias e Confissões#Visit or Memories and Confessions#Woman on the Run#Colegas#Pals#Anticipation of the Night#Zero fucks given#Rien à foutre#Allemagne 90 neuf zéro#Germany Year 90 Nine Zero#The Driller Killer#Outside Noise#Top Hat#Lady Lazarus#august 2022

153 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean-Luc Godard - Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991)

735 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean-Luc Godard - Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991)

474 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean-Luc Godard - Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991)

592 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean-Luc Godard - Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991)

273 notes

·

View notes