#“Lord can we just clear up the issue of of pagan magic because I’m just turning forty and don’t want to go bald please???

Text

More Encanto ramblings:

You remember that priest? Father Flores, I think his name is in the script? The one who went bald?

How come he never went to Julieta for a cure?

Or is it a bit like Agustín and Mirabel’s glasses, if it’s not a strict bit of damage to the body then it doesn’t count?

#encanto#julieta madrigal#father Flores#seriously though#what are the limits#and what did he think of this#prayers must have been weird#“Lord this teenager in the marketplace just qualified for sainthood seventy times in about half an hour what do I do#“Lord I pray for rain for my crops and another teenager storms by in a huff and strikes the field are you trying to tell me something?#“Lord can we just clear up the issue of of pagan magic because I’m just turning forty and don’t want to go bald please???#confessionals must have been weird too#“Forgive me Father but I heard you complaining about your back from the other side of the valley#maybe my tia can take a look?#“Father I have an unhealthy fixation with perfectly symmetrical donkey piles#“So what are the penalties for disguising oneself as a priest again? Did I get your hairline right though?#I feel for the guy#it must have been so strange at first

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

I hope you don't consider this too prying, but are you strain_of_thought? If so, I love what your doing with RWBY. I've always thought the strongest thing about RWBY were how the allusions played into the characters and story, but I always thought it didn't really use them as much as it should. All of your ideas paint the idea RWBY is using them far more effectively than I thought you could! One question, where do you look for allusions? You make some connections I would never think of.

I _am_ Strain of Thought! I also go by Karma Chimera in some places. This blog was supposed to be for posting concise, thorough, and well-formatted explanations of allusions I’ve found in RWBY, but unfortunately I’ve really had very little time to devote to it over the past two months due to crazy life events. Also, my thoughts on how the big theory should be organized and presented have been constantly evolving, largely as a result of having nice people who humor my attempts to explain it to them, and that’s somewhat held up producing finalized presentations. Most of the G.U.N. theory has been informally described in back-and-forth conversation over on my Discord server, but it’s very, very long and a mess to slog through.I want to be clear, before I get into this: the stuff I talk about on reddit and here and on the wiki and the RT forums and on Discord is not stuff I figured out overnight. I was a passionate but casual fan of RWBY who wasn’t into RT at all and didn’t even start watching the series until late summer of 2016. I was deeply haunted by Pyrrha’s death after finishing Volume 3 and dwelled on it for several months without finding any understanding of it; I wasn't even able to bring myself to watch Volume 4 until the last episode had been posted. Then, about five months ago, I had a sudden epiphany about one character- which in short order lead to another, much much _much_ bigger epiphany about another character that completely changed my perception of the show; since then I’ve been tearing the show apart piece by piece with an obsessiveness that still hasn’t really abated at all. At this point, I have spent many hundreds of hours researching the allusions in RWBY. So please don’t feel bad for not having immediately caught all of the things I point out. I had to _work_ to find them, and I didn’t begin to see them for a long time.That said, let’s talk about that first epiphany.The basic method I use for looking for allusions in RWBY is something you might call the “Cast of Characters” method. First, take a RWBY character who has an overt literary allusion that you're certain of- let's say Penny. Then list all the important supporting characters in the story of the inspirational character who the RWBY character alludes to. For Pinocchio that would be Geppetto, The Blue Fairy, Jiminy Cricket, The Puppet Show Master, The Fox and The Cat, The Coachman, Lampwick, and The Terrible Dogfish. Now, you can’t really tell the story of Pinocchio without having all of these characters also represented in some capacity. RWBY does have some characters who appear to overtly play some of these roles: Penny’s ‘Father’ is Geppetto, Ciel Soleil is The Blue Fairy, and Ironwood is the Puppet Show Master. But other important characters are conspicuously missing- Jiminy Cricket, for example. So go down the list and ask: “Who is playing this necessary role in order for this story to be told?”Doing this successfully often requires a lot of familiarity with the work in question, which means you often have to go back and actually _read_ something you’ve only picked up on through osmosis or adaptations. Sometimes you’re going to need to sit down with some 19th century children’s literature for a few hours before you’ll be able to pick up on the subtle cues that are hidden in RWBY. Reading material _about_ the work, such as Wikipedia articles on the individual characters, can also be hugely instructive.Getting back to Penny Polendina and the search for Jiminy Cricket- who is Penny's conscience? Who tries to answer her difficult questions and guide her morally and keep her out of trouble? Who is a Christ-like figure, especially in their purity of heart? (No, seriously. ‘Jiminy Cricket’ is literally a bowdlerization of ‘Jesus Christ’. Carlo Collodi never named him, simply calling him ‘The Talking Cricket’, so Disney named him after a clean expletive.) Who is repeatedly separated from Penny and ultimately fails to keep her out of trouble but nevertheless provides an example that inspires her and helps her become a much better person in the long run? _Who can jump really high?_Realizing that Ruby Rose is Jiminy Cricket, and that the writers had snuck that right past me in plain sight, was the first forehead slap that made me suspect there was much more to RWBY than what meets the eye. You can take the “Cast of Characters” method and systematically run every character in the show through it; if you do, some startling connections can jump out at you fairly quickly. Also, for RWBY characters with mythological, legendary, or historical origins, there’s often a wealth of supplemental information to be found about their supporting characters outside of their source stories themselves.For another example: Has it occurred to you that there might be important supporting characters in _Joan of Arc_’s story? Reading up on Joan of Arc, you’ll find that she consistently described her visions as always containing the same three saints: Saint Michael, Saint Margaret of Antioch, and Saint Catherine of Alexandria. We can read up on these three saints in turn, and in doing so we learn some interesting facts:Saint Michael is actually the Archangel Michael, revered by military orders as a soldier who is the leader of God’s armies and battles demons, but also paradoxically strongly associated with medicine and tranquil, healing waters. He’s an angel of mercy: he repeatedly prevents deaths, and is specifically named as the angel who provided the ram to prevent Abraham from killing his own son Isaac. Most remarkably, Michael is strongly associated with Christ, and many protestant traditions have held that Michael actually _is_ Christ in his heavenly, pre-incarnation form.Saint Margaret of Antioch was the daughter of a demon-worshipping pagan priest, who abandoned her as an infant when he had a vision that she would become a Christian. She was raised by a Christian nurse who took her in, and became a shepherdess as a teenager. As she grew up she developed a fanatical, virginal devotion to Christ that bordered on romantic fixation. She resisted worldly temptations by a pagan lord who saw her herding and was captivated by her beauty, and she kept her faith through being tortured by him after her rejection. Eventually, she faced and was swallowed by a demonic dragon, but was able to escape from its belly because the cross she wore irritated the dragon’s stomach so much that it vomited her up.Saint Catherine of Alexandria, lastly, is an absurd Mary-Sue even by biblical standards: she is not just a saint but also a martyr, a brilliant scholar, and a _princess_. She brought _herself_ to Christ through study and boldly appeared before the emperor of Rome to rebuke him for his cruelty. The emperor summoned _fifty_ pagan philosophers to argue against her, and she defeated them in debate one after another _and converted them to christianity_, prompting their immediate executions. She was whipped and imprisoned, but hundreds of people came to visit her in the dungeon and she converted all of _them_ as well, including the emperor’s _own wife_. The emperor attempted to use torture upon her, but every torture device used upon her magically broke, including a massive breaking wheel she was strapped to that was specially built to kill her. Even when she was finally beheaded, her body was carried away by angels and placed upon Mount Sinai where God spoke to Moses; there her body remained fresh without rotting, her beautiful hair never stopped growing, and she continuously issued a ‘stream of healing oils’.Are you seeing any patterns here? Can you think of three people in Jaune’s life who exhibit some of these traits? I hope you can! Now understand: I knew basically _nothing_ about Joan of Arc when I started this other than the basic “Hears voices, drives the English out of France, gets captured and burned at the stake.” bits that you can pick up through cultural osmosis as an American. I vaguely remembered her liberating Orleans entirely because of a campaign mission in Age of Empires 2. You ask where I look for allusions- my answer is, I pick a character and just start reading things about them until I feel like I’ve exhausted the resources I know to look at, and then I move on to the next one. Then later I end up coming back for additional passes with a fresh sense of what I’m looking for and what to read, and a better sense of how the show is written, and find even more connections. RWBY has given me ten times the education in western literature that college did, and even if I’m wrong about everything, I still want to thank the creators of the show for that. They couldn’t get me to read the _Iliad_ in school, but I cracked it open and tried my level best for Pyrrha.Not only does taking the thorough approach and investigating seemingly less promising character allusions like Joan of Arc allow you to find layers to the show you’d likely never pick up on otherwise, but finding who _else_ a RWBY character is drawn from besides their overt, top-level allusion often becomes very instructive in understanding them and the ways that they differ from that top-level character. I’ve repeatedly had my perception of a RWBY character completely changed by discovering some lower level allusion that recontextualizes them, and I’ve found paradigm-shifting revelations in sources as diverse as black-and-white 1950s American western films, the works of Dr. Seuss, and episodes of _Sesame Street_. I’ve generally found that the top level character allusion informs a RWBY character’s personality more (and obviously their appearance) but the immediately underlying character allusion has a much bigger impact on their story and character arc- and sometimes there are third and fourth and even _fifth_ level allusions with major impacts on a character. In one case, the layers of significant allusions go down to a _dozen_. What took me almost all of the past five months to realize is that RWBY characters are designed exactly like RWBY weapons: they’re crazy awesome mashup combinations of multiple completely different things that externally _appear_ to just be extra cool versions of one thing, but then at critical moments they perform dramatic, spectacular transformations to reveal other essential aspects of themselves that have existed within them all along.For all the reasons I’ve mentioned already, if you want to be able to perceive the allusions within RWBY, the most important thing is to just experience the world of literature it’s drawn from. In the interest of helping fans do that, I’ve started a regular weekly online film viewing group where RWBY fans can watch and discuss films together whose stories RWBY alludes to. The group is open to everyone and based from my Discord server. If you want to learn more, or maybe just watch some good films, come check it out:https://discord.gg/PMNSfhK

#answer#essay#RWBY#The G.U.N. Theory#RWBY Movie Matinee#Penny Polendina#Ruby Rose#Jaune Arc#Pinocchio#Jiminy Cricket#Joan of Arc#St. Michael#St. Margaret of Antioch#St. Catherine of Alexandria

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part Three: Rule of Three

Photo Credits: here

In this next part I want to talk a little about some important texts for the context of this project. One of them is the Canon Episcopi, a 10th century medieval canon law. For anyone who doesn’t know what “canon law” is, it is basically a written guideline authored by some church authorities and used to govern the church, its clergy, and its patrons. It’s important to highlight this text because it gives us a clear idea of what surviving pagan cultures looked like in Medieval Francia (modern France), but not in the way you might expect. As mentioned above, a lot of what we know about the past is just really good detective work, and this is one of the instances where a document helps us understand far more than what was originally intended. It’s a cohesive set of ideas that suggest how the church should treat several circumstances regarding their local pagans, and as usual, it wasn’t preaching tolerance. In summation, it called anyone who believed in anything other than Christianity an infidel.[1] Pagans still existed, and still do to this day, in fact, but the Church used a heavy hand when dealing with them most of the time. Often, they used their own beliefs against them and merged popular Christian anecdotes to help assuage people who were not happy with the idea of conversion to a new religion. I think that the author of the overview for this document said it best when they said that,

“new Christians [did not] simply cast aside old beliefs…conversion was a dynamic process…[and] elements of indigenous religious practice were frequently mixed, often deliberately, with Christian belief and ritual…Certain practices can be said to have ‘survived’ the process of conversion…After all, nearly every Christian ritual had some sort of pre-Christian antecedent or model.”[2]

They just simply couldn’t kill them all or threaten everyone with violence in order to bring them to their knees before the Lord, and so, they got creative.

Canon Episcopi calls anyone who believes in the mystical arts a liar and, what I’m most interested in is it’s mention of, “wicked women, who have given themselves back to Satan…[who] in the hours of the night…fly over vast spaces of earth.”[3] You just can’t get more witchy than that folks, and don’t worry, I know that this was written in like 900CE, but I should also mention that it was referenced in another important document—Corpus Juris Cononici, a canonical law that remained intact beginning in the 12th century all the way until 1917. I’m not going to attempt the math there, but it’s too damn long and we can all agree on that. So, now we know our Collective Catholic Opinion (CCO for the rest of this project),[4] is that we don’t like pagans, and with the introduction of this new text, witchcraft is now a pagan practice. This was originally, a really good detail to hammer out in canonical law because it typically kept the Inquisition from meddling in matters of alternative religions, UNTIL (you knew that was coming, I already warned you in Part 1) Canon Episcopi was thrown out by Pope Innocent VIII in 1484 (not the same Innocent One as before, but damn did we not learn a lesson?). Anyway, the most innocent pope of all time decided that witchcraft was to be forever tantamount to devil worship which was what gave inquisitors permission to go after pagans and those accused of practicing witchcraft—great.[5]

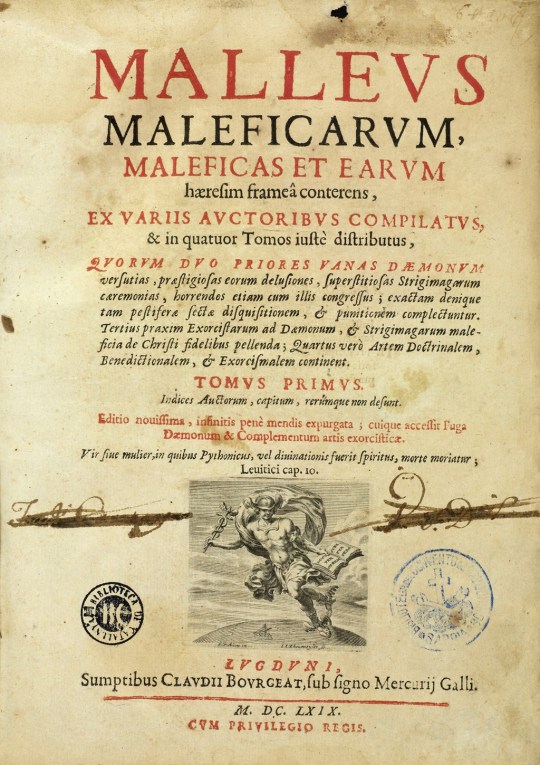

So, that brings me to my next document of importance, the Malleus Maleficarum, the Latin here, in case you aren’t a weird Disney fan, is where we get the word ‘maleficent’ and thus the name for one “Mistress of Evil”…moving on.[6] This book was written between 1486 and 1487 and can also be referred to as “The Hammer of Witches,” a direct translation of the original Latin. It was written by some German Dominican monks—'Dominican’ here, refers to the Dominican order of Preachers founded in France by the Spanish priest St. Dominic, so, not the islanders as I was originally very confused about. Recall from earlier that the first instances we see of witch trials occur in a German-speaking part of Switzerland, so you can see how this thing is gaining speed. There were other texts along the way that were written in regards to witchcraft, but there was a really important invention that made this one unique—the printing press. It spread like wildfire, and there were more copies of this document than any other, and it so precisely aligned with the mounting witch-craze, the Inquisition, and the Corpus Juris Cononici, that it almost seems planned. Am I a conspiracy theorist, you ask? Maybe. After researching this project, I’m beginning to wonder, myself. Let’s indulge.

In 1481 Pope Innocent VIII (I’m so surprised), heard about those German monks who were in the middle of writing about these witches, and they complained to him that the authorities weren’t properly looking into the accusations. This actually prompted the Pope to issue one of those papal bulls we all know and love, titled, Summus Desiderantes Affectibus, translated—Desiring with Supreme Ardor. It wastes no time getting right to the point, those who were practicing witchcraft were to be henceforth considered heretics, and doling out the full support of the Church and the Faith to inquisitors to prosecute these cases as they saw fit. Three years later, the monks published their instruction manual for other sympathizers. This document was separated into three parts. The first was addressing skeptics and assuring them of the reality of the situation and suggesting that not believing in the existence of witchcraft was another form of heresy. The second part included proof that real harm was caused by magic, and the third part was made up of guidelines for investigating, arresting, and punishing witches. It was used by Catholics and Protestants alike, and while it was never made official by the Catholic Church, it was most assuredly referenced. It was not continuously in print; however, but was re-printed and widely distributed in areas “as needed,” meaning that when prosecutions started ramping up in some areas, the press would begin to print and distribute more.

I’m gonna delve pretty deep into this document because it’s really important that we know where some of this information comes from in reference to future prosecutions, tortures, and accusations of presumed witches. The manual directly mentions that witchcraft is found amongst women most predominantly and uses the idea that both good and evil manifests in women more powerfully than in men. It specifically singles out midwives because of their aptitude for contraception and pregnancy termination—see, you guys thought this anti-abortion culture was new…it’s not. It made wild claims that midwives ate babies, or offered them to devils, and elucidated pacts made with the Devil, sex with incubi, possession, and, I’m not quite sure how to word this, the act of vanishing penises (That’s the best I can do here. I tried some other stuff and believe me it was much worse). The part I love most is that most of the references used to substantiate these claims come from some of the great Greek philosophers and writers like Homer and Socrates, who were big, giant, probably gay,[7] pagans. I can’t love that more, guys…it really doesn’t get better than two homophobic, misogynistic, intolerant religious zealots getting their entire bibliography from some gay pagans. Finally, what the document describes as “quarrelsome women” could not be considered witnesses to witchcraft, and it excuses this by alleging that this is to prevent friends, families, and neighbors from bitter fights.

To determine whether or not someone was a witch, they could be examined physically. Any corporeal evidence might include marks on the body, physical objects that were concealed on the body, or not weeping while being tortured or when presented in front of a judge. When checking for these “marks,” women were stripped of their clothing (by other women), their hair was shaved—this could be a small amount or all of it depending on where that pesky devil’s mark was going to be found. Often, this mark could be a mole, a flea or insect bite, a birth mark, or a speck of dirt. Anything passed, really, and once these marks were found they needed to make sure that there were no other instruments of witchcraft on a person in order to execute them. The manuscript mentions that if these items are not removed, there would be an inability to burn or drown the witch, and the same goes for if she was still under the protection of other witches. The practice of drowning or burning an accused witch to prove her innocence began, and although the accused was never around to celebrate her liberation afterwards the practice persisted, nonetheless. While determining the guilt of these witches, a confession was paramount in determining the outcome of a person’s wellbeing after the trial.

Accused witches could only be executed by the inquisitors or authorities of the church if they confessed themselves, but, remember that the church had already authorized torture as an acceptable method of questioning at this point and could be persuaded into confessing by any means necessary. Often, they would confess quickly under the pain of torture, and were said to have been abandoned by the Devil. Conversely, those who held out, were under the Devil’s protection and more closely bound to him, and torture was viewed as a form of exorcism. Confession under torture was not enough; however, and they had to confess again while not being tortured for it to be a valid confession. If the accused continuously denied the accusations the church was not permitted to execute her, but they could eventually turn her in to local authorities who were not beholden to the same restrictions.

After a confession, the accused could be offered the option of repenting against all prior acts of heresy and perhaps be granted the avoidance of a death sentence, but later when I pull out the statistics, you’ll see precisely how rare that option was. They were also likely to allow a witch to avoid a death sentence if they snitched on other witches, but typically the investigations into those that were implicated by the original witch were presumed to be innocent until a thorough investigation could take place. Prosecutors also did not have to reveal that the removal of a death sentence did not mean that they could not imprison them indefinitely. Judges that presided over these trials were given specific instructions on how to ward themselves from wayward spells of the spurned witches on trial, and to ensure that they had the full cooperation of those amongst the court and spectators, there were specific instructions that allowed those who were uncooperative to be excommunicated from the church or even labeled heretics themselves if their obstruction was persistent.

Pope Innocent VIII’s bull acted as a metaphorical magnifying glass over the ant that this situation was in Switzerland and Germany, but to conflagrate things further, in 1501, Pope Alexander VI[8] issued a new papal bull, the Cum Acceperimus,[9]that extended the reach of prosecutions for witches to Lombardy and officially broadening the reach into Italy. I think it’s important to point out that this particular pope was a Borgia, and for those of you who haven’t seen The Borgias on Showtime, the Borgia family is basically the Kardashian/Jenners of the Medieval world—so many scandals and orgies, one can nary keep up. Beginning in 1500 and all the way through 1560, historians consider these few decades to be the peak of trials in Europe, and in order to focus more in-depth on this aspect we’ll be ending this part here, but it may be worth mentioning that this oddly severe belief in superstition beginning with the Malleus Maleficarum, may have been one of the many sparks that stoke the flames of the Protestant Reformation in Europe.[10]

[1] See Canon Episcopi for a full quote, but this is in direct reference to a bible verse from John 1:3 that makes mention of God being the maker of all things and suggests that those who believe that other entities may have done so are “infidels.”

[2] (Traces of Non-Christian Religious Practices in Medieval Pentitentials, n.d.)

[3] Direct quote from the Canon Episcopi and shortened for clarity and pointed reference.

[4] Please don’t talk to normal people about the CCO, it’s not a real organization, and outside of this context it’s probably very offensive to modern Catholic practitioners and I am not looking to get cancelled on Twitter

[5] (encyclopedia.com, 2019)

[6] Maleficent is defined by Webster’s as, “doing evil or harm; harmfully malicious,” and the original Latin form is maleficentia.

[7] the ancient Greeks were partiers and lovers, man

[8] Not a safer name than ‘Innocent,’ it turns out.

[9] DON’T YOU DARE GIGGLE AT THAT NAME

[10] It’s important to note here that history doesn’t have a large grasp on one specific event that might have been what caused this leap, but it was more likely a combination of quite a few different things, but it is my own humble opinion that torturing people certainly wasn’t a good way to rally support for the Catholic Cause™

#witch#witches#witch trials#european witch trials#malleus maleficarum#pope alexander vi#historical texts#history#itshistoryyall#coronavirus#covid-19#quarantine#social distancing#pandemic#2020

0 notes

Text

The Wizard of Grog: The Scourge of Caster Supremacy

(This is by Elizabeth Lavenza and not by me)

Elizabeth “Linguafoeda Acheronsis” Lavenza

Chances are, one of the first images that pops into your head when you think about Dungeons and Dragons is the classic lineup of a fighter, a wizard, and a thief exploring a dungeon and valiantly overcoming obstacles together (that is, if you aren’t a mid-90s fundamentalist christian who associates D&D with pagan orgies and human sacrifice). It’s a decent enough setup, and that combined with nostalgia and inertia have allowed it to persist as one of fantasy gaming’s most common templates. But if you ask an experienced D&D player to tell you how that setup has worked out for them, a lot of times their version will have the wizard (or cleric, or druid, both of which have been even more unbalancing) effortlessly blasting every obstacle out of the way while the fighter and the thief sigh and wonder if it’s too late to reroll.

Their disappointment is understandable, not just because being useless isn’t much fun. None of the sources of inspiration- Lord of the Rings, The Princess Bride, Conan the Barbarian, Berserk, and so on- that they’ve brought to the table would have prepared them for this problem. Most fantasy literature doesn’t have scenes where the knight and the rogue sit around playing cards while the wizard solves everything (then again, most good fantasy literature doesn’t have perfectly delineated archetyped parties). You’ve heard the horror stories. Order of the Stick wasn’t lying when it had a Druid tell a Rogue that he had special features more powerful than her entire class.

I won’t spend that much time on 3e caster stories (google “codzilla” or “caster supremacy” if you’re curious), but I’ll provide a short explanation of why the problem persists, particularly in D&D and related systems, for those who haven’t encountered it before. Basically, when fighters level up they hit things for more damage and can take more damage, along with some other things. When casters level up they can pretty much control reality at will. Even beyond overpowered combos and obscure feats and munchkin builds, the simple fact remains that the class that lets you fly, turn invisible, teleport, shoot fire really well, and pretty much anything else is going to overshadow the one that hits things hard. To zero in on one particular example, there’s the legendary Druid Bear Singularity. Basically, a bear is often stat-for-stat a bit better than most Fighters of equivalent level. A Druid can have a bear companion, and also turn into a bear, meaning that a Druid with just those two basic features is equal to about 2.5 Fighters. And as the Druid levels up? They get more bears and stronger bears. They can also cast spells as a bear, and cast spells on their bears. This is when the math breaks down and the Druid becomes a Borg-like swarm of invincible magical bears.

Before I go into the general types of solutions, I should note that things are getting better. While the problem persists within D&D, Pathfinder, and other D&D-3.5-derived systems (OSR games have a fair amount of variance, “meat-grinder” early addition-likes tend to have less of a problem with druidgods and wizardgods), due to fanbase stubbornness, it’s much less present outside of those systems, and that is due in no small part to the rise of storygaming and rules-light or rules-medium games. While the overarching reason comes down to these games being willing to do things differently, if we zero in we find that one of the most powerful tools for combatting caster supremacy is one that rules-light gaming uses frequently: focus. There is no one solution for the superwizard’s trap, and to avert it you have to start with the thing you should always start with: asking yourself what kind of stories you want to tell. Each of the potential approaches lends itself to certain types of stories and foci, and resistance to them comes from the enemy of focus: grognards wanting their preferred game to have everything they’re used to in it simultaneously.

So, let’s go over the scenarios in which caster-induced redundancy isn’t a problem, and their relation to the central idea of focus. These solutions break down into two main groups: tone down the magic, or share the magic. The first of those is one that resonates most with what the classicists among the grognard host want. After all, how many times were battles in Middle-Earth won by an itinerant sorcerer blasting orcs away with magic missiles? Magic was restricted to a few individuals, or inherent powers of magical creatures, and even when they showed it off it was often rather subtle. The Game of Thrones setting, another grog favorite, also gives us a setting where magic is rare, scattered, and rarely as overt as flying bears or teleportation. It’s a completely valid approach: set up your system and story for a group of characters with no magical powers, or immensely limited and narrow magic, and things fall into place nicely. The knight, the archer, and the assassin will all have niches to fill, and they won’t have to worry about overshadowed by the druid if all the druid can do is perform long and complex rituals that allow them to see through the eyes of animals (as opposed to summoning invincible armies of them).

Of course, sometimes magic has quite a lot of punch behind it, but there are still clear advantages to those who prefer more mundane methods. The idea that magic is dangerous and costly is bandied about quite a lot, but what consequences does the average D&D wizard face from throwing around spells all day, other than potential GM ire? And sure, the Vancian system can be a drag, but once those levels climb up Wizards build up more than enough contingencies, not to mention those with ways around it all together. If all magic required costly materials and/or long rituals, then being able to swing a sword, sneak, or shoot arrows or bullets well becomes a lot more useful, even if the magic has amazing capabilities. And, if you keep the principles of story and focus in mind, you can use that setup to generate plenty of potential plots and conflicts. Imagine how warfare looks- rival sorcerers preparing their rituals in the keeps of the patrons who supply them with their materials, while both sides send their companies of sellswords and assassins across the line to try to interrupt the other side’s big ritual. Again, it’s a more fun scenario than bear-summoning munchkinry solving everything.

And what about the other kind of cost, genuine danger? Like most of these solutions for the caster problem, it’s shown up in plenty of stories. This approach has been explored in plenty of tabletop role playing games, too. Both versions of the Warhammer RPGs have magic wielders who can do some pretty amazing things…but actually doing those things is truly, actually dangerous, enough so that they aren’t things that can be relied upon to regularly solve problems. Unknown Armies, another great example, even explicitly states that magic is almost always much less useful than a gun in a combat situation, and that’s not even mentioning the massive costs it leverages on its practitioners. But the grog barrier keeps these approaches from working their way into D&D, as caster players are loathe to give up their cool powers, even if they insist they don’t want to render the nonmagical classes useless.

The grog problem brings us to the opposing approach, where the system addresses the issue of godlike mages eclipsing warriors and thieves by giving the warriors and thieves godlike powers of their own. Dungeons and Dragons, in fact, has even made its own attempts to go down this path via the Tome of Battle, which provided several new martial classes with quasimystical powers. It wasn’t really the best supplement, especially since the new classes were essentially just better versions of existing classes, but the writers were in sort of an awkward situation since actually doing what they had set out to do would require rewriting quite a bit of the rules and core classes. But the negative feedback the book generated (the feedback that specifically bemoaned fighters having these abilities, not the way in which the book implemented them) was what made me realize the role of grog in keeping caster supremacy alive.

Attempting to give martial classes their own ways to, for example, attack large groups or alter local terrain or fly will always provoke the “it’s too anime!” grog-whine, which is stupid on a number of levels. Even if one tries to see eye to eye with what people mean when they describe something as “too anime”, the fact remains that the idealized game as it exists in their heads can’t really existed without restricting casters far beyond what D&D does (see the previous paragraphs for information on this approach). They’ll often bring up that Conan or Drizzzzzzt (no, I’m not going to look up how many z’s he has) or so on and so never shot air blades out of their swords or flexed so hard things exploded, ignoring that these characters either existed in worlds with vastly different magic from their preferred game systems or had massive amounts of authorial fiat on their sides.

Generally, the best way to get grognards to accept the “make fighters magic” approach is to bring up comparisons to mythology, where sorcerers were generally pushed out of focus in favor of demigods or magically enhanced warriors with enough musclepower to lift and throw mountains or fistfight storms. But even if you use this approach, you’ll still get complaints that it isn’t gritty enough, or that it makes it hard to run standard dungeon crawls, and so on. But caster supremacy is a problem that can only be fixed with genuine change. You can’t have that specific kind of team-based gritty dungeon delving if one party member has nearly unrestricted godlike powers, and if you want to have party members with that level of power, the other players should be able to reach it to, even if that means basing your world around a unified system of supernatural power that can harnessed by warriors as well as sorcerers, or putting the whole thing in terms of mythical dream-logic where being good enough at something like weaving or lying means you can apply it to abstract concepts (as an aside, Exalted does do the “mythic” approach fairly well, and there are plenty of games like Don’t Rest Your Head or most permutations of World of Darkness where it’s assumed that each member of the party has their own formidable reserve of supernatural power). Narrative-based powers provide a more subtle way to balancing, by giving characters an in-game ability to invoke the narrative tropes that help fighters and rogues equal casters in fantasy literature. PBTA systems are particularly good at this, but it’s something that’s been worked into an increasing number of systems.

Of course, there are countless permutations of these approaches. For example, you could run D&D 3e without many changes, as long as you gave up on pretending it was balanced and only allowed parties of equally-powerful classes, and constructed a setting in which magic-wielding demigods rule over mere mortals with their puny swords and bows. And, of course, you need to have a group of players who want to explore the ramifications of a setting where politics are dominated by human superweapons, rather than players who want to be Conan or Aragorn. Ironically, even the kind of dungeon-crawling stories associated with D&D acquire focus and planning to establish, and aren’t particularly well-served by God-Wizards and require a willingness to accept system refinement and storygaming to bring to their full potential. But fear of change and idealization of the past gets in the way, as always.

In conclusion, fucking grognards. In a more serious conclusion, you can’t fix a problem if you keep doing the same things and expect them to work, and you can’t do everything at once. The start point for tabletop gaming should almost always be “what kind of story do we want to tell together”. Even if the kind of story you want to tell is based on your ideal of classic D&D or an amalgam of various fantasy literature you’ve absorbed, you still need to set things up to focus the story on that. If you want to use teamwork to crawl dungeons or fight evil hordes, you need a game that’s built for teamwork, and not endless swarms of magic bears making all the other players redundant.

About the author: Elizabeth Lavenza is a lizard who can type. More information possibly to come.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sensor Sweep: Battle Tech, Manly Wade Wellman, Savage Heroes, Space Force

Science Fiction (Tor.com): Anyone who has played Traveller (or even just played with online character generation sites like this one) might have noticed that a surprising number of the characters one can generate are skilled with blades. This may see as an odd choice for a game like Traveller that is set in the 57th century CE, or indeed for any game in which swords and starships co-exist. Why do game authors make these choices? Just as games mix swords and starships, so do SFF novels. The trope goes way back, to the planetary romance novels of the Golden Age. Here are five examples.

Fiction Review (Legends of Men): Savage Heroes is a sword & sorcery anthology that’s pretty rare in the U.S. That’s because it’s a U.K. publication. The first S&S anthology I reviewed was Swords Against Darkness. It’s a great anthology that came highly recommended by an expert scholar in the field. Savage Heroes is better though. It captures very well the combination of historical adventure, lost world fiction, and cosmic horror that makes Sword and Sorcery unique.

Fiction (Wasteland & Sky): Hard-boiled noir is an interesting subgenre. It’s mostly remembered in the mainstream, if at all, for cheesy parodies that family sitcoms and cartoon used to do back in the 1990s. What it is remembered for is as a genre about hapless detectives in black and white 1930s settings having to find a killer among a cast of twelve or so shifty character archetypes. Plenty of fun is poked, but they hardly take the genre seriously.

Science Fiction (Scifi Scribe): We’ve all seen the memes, right? The minute the world started talking about the mere idea of a United States Space Force, we were all instantly greeted by “LOL, Space National Guard/Space Force Reserves!” All joking aside, the irreverent interservice banter and, shall we say, “robust,” back-and-forth on social media reflects the very real, and very important, national-level discussions about creating a new military service branch.

Cinema (Jon Mollison): The birth of Dungeons and Dragons is a strange and fascinating story of how creatives can draw forth order from the froth of chaos. I went into this film expecting a lot of defensive snark about how Gary Gygax was a Johnny-come-lately who yoinked the idea of RPGs out from under Dave Arneson’s nose. A fraudulent Edison to Arneson’s Tesla, if you will. And there are hints of that within this film, but only hints.

Art (Mutual Art): Theron Kabrich quietly gazes at Roger Dean’s watercolor, The Gates of Delirium. He has been Dean’s friend and representative at the San Francisco Art Exchange for thirty years, selling his paintings, drawings, and prints to an international audience of collectors. Millions of copies of the image have been made. If Tolkien’s timeless classic inspired Dean’s enduring fascination with pathways at the beginning of his career, it is Robert McFarlane’s writing about wandering journeys along the ancient tracks twisting through the British landscape that have his attention in the present.

Art (DMR Books): Stephen Fabian, as I’ve pointed out before, is a living legend in the fantasy art community. His output from the 1970s to the 2000s—both in quality and quantity—can only be called astounding. I covered some of that in my three-part series on his Robert E. Howard-related art. However, a friend of mine recently brought Fabian’s artwork for In Lovecraft’s Shadow to my attention. That book, in some respects, may be Stephen’s greatest sustained work. In Lovecraft’s Shadow was a collection of August Derleth’s Lovecraftian fiction published in 1998 through a joint venture by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box and Mycroft & Moran.

Review (Tea at Trianon): I remember as a twenty-two-year-old being excited when I saw a new book called the The Mists of Avalon by an author called Marion Zimmer Bradley. Mists was presented as the retelling of the Arthurian legend from the point of view of the women of Camelot, which I thought was a thrilling idea. However, I found the book heavy on paganism and morbid, explicit sex scenes, but light on romance, heroism, chivalry, mystery, faith and all the qualities I had come to love in the Camelot stories. This brings us to Moira Greyland’s recent book, The Last Closet: The Dark Side of Avalon.

Fiction (Adventures Fantastic): I’m going to look at three of his stories that feature the same character, Sergeant Jaeger. First is “Fearful Rock”. Originally published in the February 1939 issue of Weird Tales, the central character of this novella is Lt. Lanark. He and Jaeger are leading a cavalry patrol in Missouri during the Civil War, looking for Quantrill. What they find is a young woman being sacrificed by her step-father to the Nameless One in an abandoned house under the shadow of a formation known as Fearful Rock.

Fiction (DMR Books): Tanith Lee was a force to be reckoned with in the ’70s, ’80s and on into the ’90s. She exploded onto the SFF scene with her debut novel for DAW Books, The Birthgrave. That book was labeled at the time as being “sword-and-sorcery”. I would probably call it heroic fantasy, but it remains a minor classic regardless of specific sub-category. During her forty-plus-year career, Tanith published ninety novels and a myriad of short stories. Her prolificity was on display right away. She quickly followed up The Birthgrave with more notable books like The Storm Lord and Volkhavaar, along with short stories like “Odds Against the Gods” published in Swords Against Darkness II.

Science Fiction (Men of the West): The book. Not the movie. If you can even call Verhoeven’s bastardization “Starship Troopers” at all. Robert A. Heinlein is an increasingly controversial figure in recent years, moreso than he was in his lifetime. This, of course, is due to his dubious content in his later career. But he was nothing if not influential on the genre, and his early works, such as his juvenile novels (of which this was the last), remain worth a read. We may go into Heinlein’s other works later, but the focus is not so much on the man as on the book.

D&D (Jeffro’s Space Gaming Blog): I think Gygax is pretty clear about how initiative works in the DMG. (His surprise rules do make a bit of static, though.) Here’s my take on it: 1) DM decides what the monsters will do. Check reaction and/or morale if need be. 2) Players declare their actions. If they want to win at rpgs, they will advise a high t caller who will then speak for group.

Cthulhu Mythos (Marzaat): “Bells of Horror”, Henry Kuttner, 1939. This is a fairly good bit of Lovecraftian fiction from Kuttner. He uses a typical Lovecraft structure. Our narrator opens by mentioning a weird event then gives the back story of what led up to it and concludes with a not all surprising event. (Sometimes Lovecraft managed to surprise with his last lines, sometimes not.)

Authors (Goodman Games): While all of Wellman’s oeuvre is worth reading, it is his Silver John stories that most impacted the world of fantasy role-playing. Wellman is one of the names on Gygax’s Appendix N roster of influential authors. Although no specific title is listed alongside his name, it’s been suggested that the character of Silver John influenced the bard class in D&D—a wandering troubadour who uses song, magic, and knowledge to defeat supernatural menaces. Stripped of the pseudo-medieval trappings of D&D, the bard and Silver John become almost indistinguishable from one another.

Pulp Art (Dark Worlds Quarterly): It shouldn’t be any surprise that the artists that illustrated Short Stories would appear in Weird Tales and vice versa, though to a lesser degree. Fred Humiston is a good example. For many years, he illustrated half of each issue of Short Stories along with Edgar Wittmack.

Cinema (Film School Rejects): Most movie fans associate Martin Campbell with the Bond franchise and other blockbusters. However, before he became one of Hollywood’s A-list directors, he helmed Cast a Deadly Spell, a genre-bending TV movie that originally aired on HBO back in 1991. It isn’t the most known movie in his oeuvre, but it’s easily one of his most entertaining and rewatchable efforts.

Tolkien (Monsters and Manuals): I have no idea what Tolkien had in mind for the geography of Rhun and the peoples within it. But it seems to me that, while one shouldn’t think of Middle Earth as being too closely paralleled with the real world, there is a case to be made that its character is roughly akin to the Eurasian steppe this side of the Urals – more specifically the Pontic Steppe north of the Black Sea (with the Sea of Rhun here being a bit like the Black Sea).

Gaming ( Walker’s Retreat): The other day I posted a new BattleTech lore video. I mentioned that the channel posting that video did more to promote BattleTech than anything that the current owners of the property–Catalyst Game Labs–have done. All of the other lore channels and battle report channels contribute to this effort, and it helps that Harebrained’s adaptation is very close (but not identical, which it should have been) to the tabletop game, but there’s sweet fuck-all for marketing from the company itself.

Sensor Sweep: Battle Tech, Manly Wade Wellman, Savage Heroes, Space Force published first on https://sixchexus.weebly.com/

0 notes