Text

The daughters of the Tsar Nicholas II of Russia: Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova

#the romanovs#imperial russia#russia#otma#olga nikolaevna#olga romanov#tatiana nikolaevna#tatiana romanov#maria nikolaevna#maria romanov#anastasia nikolaevna#anastasia romanov

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Feodorovna

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wittelsbach sisters

3 notes

·

View notes

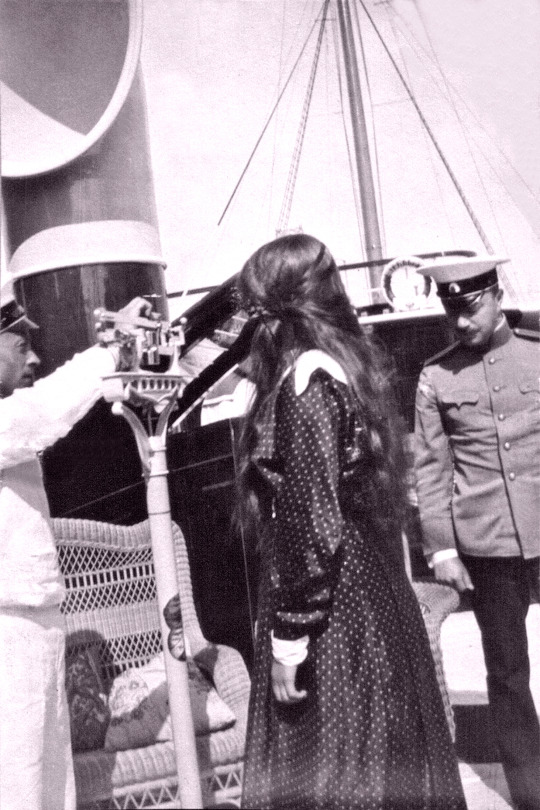

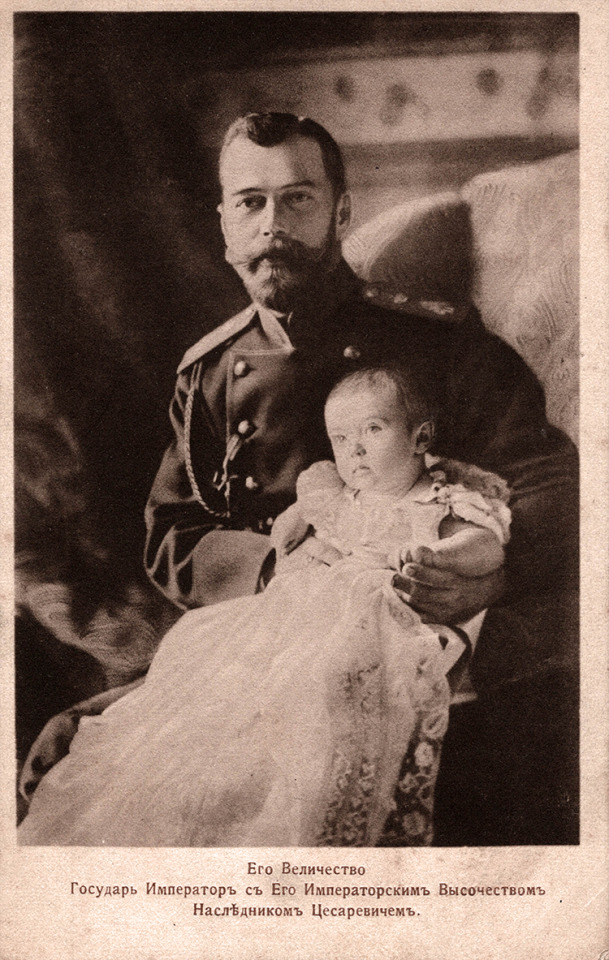

Photo

Series: Imperial Family 1904 - Russian editions.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

The beautiful Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna Romanova, the second daughter of the Tsar Nicholas II.

Beautiful, elegant, and kind, Grand Duchess Tatiana Romanov was born in one of the world's most exquisite palaces and met her bloody end in the basement of a desolate house in Siberia.

While she may not be remembered as widely as her younger sister, Anastasia, Tatiana Romanov was widely recognized in her day as the most regal of all the daughters of Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II. But despite her regal air, not to mention her legendary beauty, Tatiana Romanov’s short life came to a sad end alongside Anastasia and the rest of her doomed family.

Tatiana Romanov, The Young “Governess”

The Russia into which Tatiana Romanov was born — on June 10, 1897 in the Peterhof Palace in St. Petersburg — was a country on the edge. As was true for so much of its history, Russia was torn between pride in maintaining its traditions and fear of being left behind by the countries of Western Europe.

Unlike the monarchies of these Western nations, whose roles had largely become symbolic, the Romanov rulers maintained almost absolute power over their country. At the time of her birth, Tatiana’s father, Tsar Nicholas II, was perhaps the single most powerful head of state in the world. Tatiana Romanov’s mother, Tsarina Alexandra, was the granddaughter of the U.K.’s Queen Victoria.

Tall, slim, and beautiful with auburn hair and striking gray eyes, Tatiana had a regal presence that caused others to “[feel] that she was the daughter of an emperor.” Although she was not the oldest, she was the most organized and self-assured of the five Romanov children, leading her siblings to playfully dub her “the Governess.”

Other members of the court recalled their remarkable generosity and respect towards everyone, regardless of rank. Baroness Buxhoeveden, a lady-in-waiting to the tsarina, recalled how on one occasion, after the jewels she had selected for that evening were deemed inappropriate, Tatiana tried to lend the baroness some of her own brooches and was surprised when she refused.

In many ways, the childhood of the imperial siblings was no different from the childhoods of millions of other children. Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, aunt to the five Romanov children, described how one winter the rambunctious young Anastasia hurled a snowball containing a rock at her more restrained older sister which “hit Tatiana in the face, and knocked her, stunned, to the ground.”

Although Nicholas and Alexandra initially rejoiced at the birth of their son and heir, they were soon devastated to find out that Alexei was afflicted by the dreaded “royal disease.” The tsarevich inherited hemophilia from his maternal grandmother and the slightest bruise could send him into hemorrhages that lasted for days.

The entire family despaired, but the empress was the most affected. She quickly descended into a state of nervousness and paranoia that led one of her English cousins to nervously predict “Alicky [Alexandra] is absolutely mad — she’s going to cause a revolution.”

Tatiana Romanov was the closest of the siblings with her mother and, with her calm and efficient manner, would often be the one to soothe Alexandra’s panic attacks. Yet a touching letter Tatiana wrote during one of the many times the empress shut herself away and refused to see even her own family reveals the limits of her influence: “My darlin[g] Mama, I hope you won’t today be ti[r]ed and that you can get up to dinner. I am always so awfully sorry when you are ti[r]ed and can’t get up.”

The “Mad Monk” made himself indispensable to the imperial family through his mysterious ability to stop Alexei’s bleeding by praying over the boy (a result which may, in fact, have been due to nothing more than his ability to calm both Alexandra and Alexei’s hysteria and therefore more quickly staunch the flow of blood).

Tatiana and her sisters referred to the Siberian peasant as “our friend” and appeared to adore him as much as their mother. In one letter to Rasputin, Tatiana wrote “When will you come? Without you it’s so boring!”

Outside of the imperial family, however, Rasputin was viewed with mistrust. Rumors began circulating that Rasputin had seduced not only the empress but her four daughters as well and that he was wielding the true power in the country.

As the emperor and empress became ever more enamored with Rasputin and detached from their people as well as consumed by their own personal problems, much of the world was quickly heading toward World War I. Hostilities finally erupted in 1914, and on July 20 — a day Tatiana described in her diary as “absolutely wonderful” — the emotional tsar declared war on Germany to a cheering crowd in St. Petersburg.

Alexandra, Olga, and Tatiana Romanov threw themselves into the war effort by training with the Russian Red Cross as nurses. Tatiana even set up her own surprisingly successful committee to help refugees and managed all of the paperwork herself after returning from the hospital each day.

Colleagues at the hospital recall Tatiana as being a particularly efficient (if somewhat bossy) nurse who was able to deal with the most unpleasant operations without flinching. She even struck up a romance with one of the wounded officers she tended to in the hospital, Dmitri Yakovlevich Malama. Yet the blossoming affair was soon cut short by tragedy.

Nicholas’ grip on power began to weaken as the war continued and casualties mounted without any end in sight. Things further unraveled for the imperial family with the murder of Rasputin by their own relatives in 1916. Meanwhile, Marxists advocating for the poor and angry at the bourgeoisie were calling for the end of the monarchy.

The mounting internal pressures culminated with The Russian Revolution in February of 1917, forcing Nicholas to abdicate the next month, ending centuries of Romanov rule and sending his family into exile.

The Death And Legacy Of Tatiana Romanov

The former imperial family was sent to Siberia, the same place tsars had once sent exiled criminals. At first, they were kept in a private house in Tobolsk with some servants and ladies-in-waiting.

As civil war continued to rage in Russia, however, the Bolsheviks who had seized power began to fear loyalists would attempt to rescue the Romanovs and use them as figureheads for their movement. In April of 1918, the family was sent to Ekaterinburg, where they could be more closely guarded.

The imperial entourage was forbidden from following the family to their new prison. Tutor Pierre Gillard recalled his last sight of the children at the train station: “Tatiana Nikolayevna came last…struggling to drag a heavy brown valise. It was raining and I saw her feet sink into the mud at every step. Nagorny tried to come to her assistance; he was roughly pushed back by one of the commisars.”

The family was imprisoned in the ominously-named “House of Special Purpose,” from which they would never emerge. In the early hours of July 17, 1918, the Romanovs were summoned to the basement of the building and briefly read a death sentence before their captors opened fire.

The job was sloppily done, as most of the guards were drunk and the grand duchesses had, unbeknownst to the Bolsheviks, sewn their jewels into their corsets as a precaution which served as an unexpected armor against the bullets.

After the first round of firing, only Nicholas and Alexandra were dead. The guards went around the room with pistols and bayonets to finish the job and 21-year-old Tatiana Romanov’s short life was brought to an end when she was shot in the back of the head, spraying Olga, to whom she had been clinging, with a “shower of blood and brains.”

The bodies of Tatiana Romanov and her family were hastily burned and buried and the secret of their horrific murder was shrouded by the Iron Curtain for decades.

In the years following the revolution, rumors abounded that one of the Romanov daughters had somehow survived the slaughter. Various impostors emerged claiming to be the lost grand duchesses, but they were quickly shown to be frauds by surviving relatives. Then, in 1922 in Berlin, a patient at the Dalldorf Asylum claimed that another inmate was the Grand Duchess Tatiana.

This time, relatives who saw the silent woman could not so easily dismiss her as an impostor. It wasn’t until Baroness Buxhoeveden came to visit and immediately declared, “too short for Tatiana,” that the woman finally replied, “I never said I was Tatiana.”

The woman soon explained that she was instead Anastasia. The mysterious woman was actually named Anna Anderson and she successfully convinced a number of Romanov friends and relations that she was the Grand Duchess Anastasia for decades — though she was ultimately determined to be an impostor.

Although Anderson ensured that Anastasia would become the most famous of the Romanovs after her death, stories of Tatiana’s possible survival persisted as well. But in 2008, DNA testing successfully proved that bodies unearthed in the Siberian woods accounted for the entire imperial family. Both Anastasia and Tatiana Romanov had indeed perished, their young lives cut all too short.

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tercentenary Parade

Nicholas II, Alexandra and Tsarevitch Alexeï during the tercentenary procession at Kremlin follow by Tatiana with the Grand Duke Cyrille Wladimirovitch, Maria with the Grand Duke Boris Wladimirovitch and Anastasia with the Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovitch. (Olga and the Grand Duke Michael are cut by the footage)

341 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress that belonged to Alexandra Feodorovna.

The second photo shows a skirt detail.

(source: Ezoteriker)

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Daughters of Tsar Nicholas I and Tsarina Alexandra.

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An ill Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna of Russia with her father, mother and brother in 1913

75 notes

·

View notes

Video

Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia Romanov | Татьяна, Мария и Анастасия Романовы by Olga

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tsar Nicholas II walking with his daughters along train tracks, Sevastopol 12th - 15th May 1916.

Photo from:

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna’s 1916 Album

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana of Russia, 1913.

Original picture

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna of Russia, 1914.

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Imperial Family visits the Monument Chapel of the Battle of Saltonovka.

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Library of Nicholas II, tucked away in a corner of the Winter Palace which is now the home of the Государственный Эрмитаж.

This is my favourite room at the Hermitage – there are so many (many) opulent and beautiful rooms here, but this one is one of the smallest and quietest and, in a way, the most thoughtful and carefully crafted in its atmosphere.

18K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Massandra Palace, residence of Emperor Alexander III of Russia, Massandra, Crimea

31K notes

·

View notes