Text

imagine being so fucking brain fried you can’t tell the difference between rejecting a system which concentrates wealth, power, and the violence to defend its monopoly on wealth and power vs people asking you to not kill them by giving them fucking C0vid. also Big Pharma doesn’t give a shit if u die from covid, they literally charge the government like a billion dollars for those vaccines which are not even made universally accessible. like they don’t care.

also,how in good faith can you call yourself a communist when you don’t even care about your own community enough to not kill them from a viru s. now that’s some communal values for ya

you ever see a post that could just be read as ‘logging off is good sometime’ but it’s phrased in such a slightly off enough way to set off alarm bells that the op is like a weird anti vax anti civ reject modernity embrace tradition tradblogger with a bizarre hatred of women so you check their blog and it’s like…. yup there they are

#idiocy#anti anti vax#community#masks#politics#pandemic#tho this isn’t an accurate rep. of anti civ as a whole#false equivalents#false equivocation#leftist

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

only delma’s can reblog. the rest will be blocked

Sorry but “x group of people can reblog this” is one of the funniest phrases to come from this site. What if we don’t want to

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m sure most people have those things where they like the art but avoid the fandom, ya for me this is it. especially on tumblr like. lmaoo

also another instance of I may not have discovered this art/ media had i been first introduced to it via fandoms. actually i can think of a few artists and shows off the top of my head that I have no interest in purely bc of tumblr lol

i had no clue the hozier culture war so to speak was so intense over here on tumblr.com

#fandom#hozier fandom#hozier#celeberties#celebrity posting#music#artists#tumblr fandom#it’s a lot#lol#popular#musicblr#art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

makeup discourse is not something I feel too strongly about either way but I do find it interesting how there is this assumption that everyone grew up in a culture where they were pressured into presenting in a highly feminine way by putting lots of time and money into a maintaining a highly feminine appearance. but on the other hand, there are people (including women) who come from the opposite direction, where (conventional) femininity is demonized, scrutinized and denied to them (in various ways). where the most prevalent message is that girls who wear makeup are stupid whores who shouldn’t be respected and that makeup and fashion are a waste of time/ money. and I mean it’s one thing to critique femininity as a cultural standard, but to go all plastic straws feminism (to reference another post) and demand a new set of criteria for female presentation seems to mirror the existing ‘dominant’ narratives in the opposite direction, as well as the controlling, often hyper-vigilant attitudes surrounding (female) presentation. this also seems to follow with a particular line of feminist thought which claims that everyone of the same sex assignment has had virtually the same experiences and,,, Socialization, when that’s honestly rarely the case. I’m sure the type of environment in which someone works would also play into how these standards affect them (irt “professionalism”, gendered labor, male-dominance and traditionally masculine fields, etc)

tumblr post: women should not be obligated to wear makeup

bootlickers: just a little reminder though that it’s ok to wear makeup i wear makeup just a reminder it’s ok to wear makeup i like to wear makeup i have eyeliner wings sharp enough to kill a man why do you hate women who wear makeup i love wearing makeup let women do what they want wear makeup wear makeup wear makeup wear makeup wear makeup

#*and by plastic straws feminism I mean a hyper focus on minor Individual Choices which are not really the bigger picture#*vaspiders post on ‘comphet’ discourse#femininity#femininity discourse#feminism#makeup#makeup discourse#feminist discourse#disc horse#beauty standards#body image#cultural expectations#gender#gender roles#masculinity#I didn’t mean op personally was demanding a set of criteria for female presentation#but often the controlling and hyper vigilant attitude remains and creates new ideas of how it’s (not) ok to present

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh no someone talked about Adrienne Rich without giving even basic context for what a mess she was!

[Old lesbian screaming]

#nuance#feminism#plastic straw feminism#long post#biphobia#gender#video#tiktok#comphet#lgbt#political lesbian#gender discource#lesbianism#wlw#sexism

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s been said before, theres no cultural change without the economic (material) change to prefigure it.

My writing on Women, the State, and Revolution.

Wendy Goldman’s Women, the State, and Revolution is a thorough analysis of the circumstances of women during the 1920s USSR, with a focus on the state’s attempts to create legal and economic gender equality. Space is also dedicated to the condition of children, focusing on children who lived on the street, and to the ultimate fate of Bolshevik attempts at radical reform in the 1930s. Throughout the book, the contrast between the radicalism of the Bolshevik imagination and the limits of what was possible under the material conditions of the time is a constant theme, as repeated attempts at reform were challenged by the poverty and “backwardness” of the USSR.

Goldman begins with a brief summary of feminist history up to the 1920s, with a specific focus on Marx and Engels. The most important idea here is that the context of social relations is determined by the economic relations of the time. The shift from tribal society to feudal and agricultural societies reduced women to a subservient role, and the imagination of historical ‘feminists’ was consequently limited. Only with the advent of the capitalist system could questions of women’s liberation be raised and discussed, and in Marx and Engels’ view, only with the advent of socialism could they be answered. Upon the success of the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks quickly established the equal rights of men and women under the law, a legal stride forward that the rest of the world still struggled with. The socialist promise of economic equality would be far more challenging to deliver.

Goldman splits the Bolshevik program for women and families into four major interconnected components: the liberation of women through waged labor, the replacement of marriage with a free union based on mutual love and respect, the socialization of household labor, and the withering away of the family. Arguably the most essential of these was waged labor, as the Bolsheviks identified women’s dependence on their husbands as a cause of many of the issues women faced. War communism suggested a positive outlook for women, as men left to fight the civil war and women took their place in the factories, but this would prove to be short lived. After the conclusion of the war and the establishment of NEP, unemployment skyrocketed and men returned to take their jobs back. The ideal of women as wage workers, independent from their husbands, would not be realized in the 1920s.

The Bolsheviks introduced civil marriage largely as a shot at the church, and many of them ultimately believed that marriage would become unnecessary. Romantic and sexual unions between men and women (and only between men and women) would be based on mutual affection and respect, and there would be no need for the intrusion of the state into these private affairs. In the same vein, the Bolsheviks legalized no-fault divorce as a means of ending bad unions. This utopian view ran into the unfortunate reality of women’s economic situation, where despite the efforts of the party, they were still overwhelmingly dependent on their husbands. The Bolsheviks were forced to enact a system of alimony to allow dependent wives who had been abandoned by their husband, often with children, to extract economic support. This system was overburdened and ineffective, often running up against the simple issue that men were too poor to support their ex-wives and children, especially if they took another wife. The result was devastating for women and children.

The Bolsheviks also hoped to socialize all housework, with domestic labor being communalized compensated instead of being done by unpaid housewives. While this ideal was enacted partially during war communism, after NEP was established, it became clear that it was simply too expensive to socialize housework in this way. The “subsidy” of unpaid housework by women was too costly to remove.

Most radically, the Bolsheviks predicted that in time the family would wither away as various functions of it were replaced by the state. Most crucially, they hoped to socialize childcare, placing children in homes that would raise them collectively. This ran into the same issue that socializing of housework did. The resources to create massive state programs to raise children did not exist in the 1920s USSR. NEP gutted funding for social services, and amidst the insufficiency of what remained, Bolsheviks were forced to return to the family as a means of raising children the state could not care for. Adoption, initially outlawed, was reintroduced.

Goldman dedicates the final section of the book to the 1930s USSR and the brutal end of the libertarian dreams of the 1920s. Women finally achieved near-equal participation in the labor force, but only after real wages had fallen so significantly that a married couple’s combined salary would only purchase as much as a single man’s salary in the 1920s. Marriage was strengthened, divorce made more challenging, and legal punishments for failing to pay alimony became more punitive. The family returned for good as an essential labor unit, irreplaceable in its economic value. Abortion was outlawed, and the jurists and theorists who advocated for more radical, libertarian ideals for women and families were purged. While equal participation in the labor force did change the power balance between men and women, the changes crushed the idyllic hopes of the 1920s, and they would not be resurrected.

Women, the State, and Revolution is thorough, exacting, and relentless in driving home its core point: it is impossible to radically change the social relations between men and women without the prerequisite economic shifts. No-fault divorce for women without economic equality for women is not freedom so much as yet another way they can be exploited, equality in sexual relations between men and women is impossible while no effective contraception exists, the liberation of the peasant women is intractable while the household remains the primary unit of production, and the withering away of the family is little more than a distant dream while thousands of children that the state cannot care for walk the streets. This is not to say that Goldman condemns the Bolsheviks; she acknowledges the incredible strides forward in legal equality, the legalization of abortion, and the care the legal system took in its attempts to handle divorce and child criminality. But the reality of the incredible poverty of the 1920s USSR was inescapable, and as a result, the set of radical Bolshevik ideals aimed at reimagining the role of women and the family failed.

#economics#capitalism#anti capitalism#women the state revolution#goldman#bolsheviks#abolish capitalist social relations#abolish capitalism#politics#feminism#good post#naive politics

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Descartes was wrong: ‘a person is a person through other persons’

#descartes#panpsychism#pantheism#ubuntu#philosophy#intersubjectivity#subjectivity#spirituality#objectivity#collective subjectivity#dialogue#fedor dostoevskij#mikhail bakhtin#self#what is self#who am i#personhood#philosophyblr#reality

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

”nonbinary“ and “bisexual” are still technically categorizations, because sexuality and gender still exist, but the last part is poignant

“we are living breathing proof that any attempt to contain human gender & sexuality is doomed to failure”

and may it fail forever <3

the reason bisexual and nonbinary people get so much hate is because we challenge the idea that people can be separated into little boxes to stop them from mixing with and “corrupting” the others. doesn’t matter which bathroom i use, if they’re marked with a binary gender then i’m gonna be in there with people who aren’t my gender. doesn’t matter who i date (or don’t), there’s always the potential that i could date someone with a gender different from previous partners. we are living breathing proof that any attempt to contain human gender & sexuality is doomed to failure and i think that’s very sexy of us

#lgbtq+#nonbinary#bisexual#gender abolition#gender nihilism#gender#sexuality#lgbt#queer#boxes won’t protect you

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

if I was hozier I would make a slut anthem

#hozier#hozier fandom#celeberties#celebrity posting#tell it to my heart#2021 music#fandoms#tumblr fandom#fandom culture#artist#toxic stans#fake fans#musical artist#musicians#artist stuff#art#artblr#musicblr#popular#memes#reblog

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

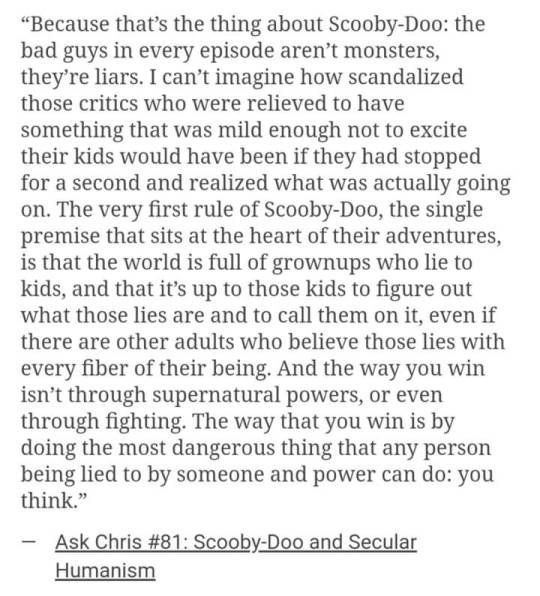

sometimes I think about changing my name to some untaken iteration of ‘scooby philosophy’ but I think that would be misleading considering I rarely touch on the intersection of philosophy and scooby doo and usually post about both separately

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#scooby doo#scooby meme#critical thinking#ask chris#scooby doo and secular humanism#thought#scooby philosophy#scooby doo fandom#scooby gang#mystery incorporated#mystery inc#velma#daphne#shaggy#scooby#fandoms#fandom tag#monsters#scooby doo critique

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

can someone tell me, is timothee chalemet still relevant, Ik he had his little moment but idk what happened to the guy

#celeberties#celebrity posting#timothee chamalet#obsessive fans#out of the loop#stans#fan culture#actors#celeb actors#celebs#minute in the spotlight#timothee fans

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i had no clue the hozier culture war so to speak was so intense over here on tumblr.com

#celeberties#celebrity posting#out of the loop#musicians#hozier#popular#fake fans#tumblr fandom#artists#fandoms#stans#fans#musical artist#hozier fandom#tumblr#tumblr.com#tumblr stuff#artist#artist stuff#lol

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Don’t explain. People only hear what they want to hear.”

— Paulo Coelho

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Music is powerful. It is the only thing that can speak into your mind, your heart and your soul without your permission.”

— Emmanuel Jal

537 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Beautiful girl, take care of yourself. No-one else knows what your soul needs.”

— AstonG

724 notes

·

View notes

Text

With a certain mindset, there can be genuine satisfaction, a genuine feeling comfort and peace in inflicting some degree of discomfort, or withholding some pleasure from ourselves. This effect is very strong if you are raised with a mindset that valorizes asceticism or moral scrupulousness–say, Roman Catholicism–but it’s true for other things also. If you worry about the environment, carefully sorting your garbage can be a way to reduce that anxiety, because at least you’re doing something; if you’re concerned about poverty, then giving money to a panhandler can feel good even if it’s not systemic change (and obviously empathy is probably part of it, too; but if you were a totally callous person you probably wouldn’t care about poverty in the first place).

Our brain can attach pleasurable stimulus (albeit one that originates from within) to neutral or even unpleasant actions, related to our self-perception and our desire to be seen a certain way by others. As a neurological feature, the former is probably related to the latter–I suspect our ability to introspect and judge ourselves along any axis, whether morality or coolness or hotness or w/e, is just taking the neurological tools of social bonding and applying them to ourselves. Primate intelligence has its origin not in internal experience, but in the benefits of external interaction, after all!

This positive attachment can be very strong, ranging from a mild satisfaction to overpowering. It would take an overpowering stimulus to make a hermit scourge himself in the desert! It can be rooted in changeable aspects about ourselves, like political opinions, or it can be rooted in very deep elements of identity, like spirituality or body image.

What is most interesting and puzzling to me is when this positive attachment is changeable and when it is not. If you become convinced to be an environmentalist, you might take pleasure is sorting your garbage, even though it’s a little bit of a chore, while if you cease to care about the environment, you might find it easy to stop. For other such attachments, like moral scrupulosity, it can be very hard to abandon those attachments to a behavior that is even actively harmful, even when you have long since abandoned the religious or spiritual environment that inspired them.

There is a strong connection here to beauty standards. I’ve seen some people point out that, while intellectually acknowledging beauty standards are BS, they still have a powerful desire to live up to those standards, and feel satisfaction in doing so. There’s clearly some module in the brain that cares deeply about them, even if the person as a whole would prefer not to. That’s super interesting! It’s strongly reminiscent of sexuality, in that sexual preferences, while forming fully only in adolescence, are often shaped by early childhood experiences–you are more likely to be attracted to people of the races you grow up around, for instance; the features of that attraction are strongly shaped by dominant beauty standards in your society; kinks arise out of the sexualization of salient cultural features, social interactions, and common social tensions (cf. cuckolding, BDSM, anxiety about unsafe sex turning into a fetish for “breeding”, sex that highlights or transgresses social rules about race and gender). And the person whose actual beliefs stand directly opposed to their sexual drives is so common as to be a cliche.

But there are things about ourselves we cannot change; what turns us on seems to be one of them. It might change a little, slowly, over time; but we know of no way you could turn yourself from a Kinsey 0 to a Kinsey 6, or vice-versa. Many kinks, even ones someone is so ashamed of they contemplate suicide (like a foot fetishist Jesse Bering mentions in Perv, who did in fact commit suicide because of that shame), seem likewise intractable. Some hangups, sexual and nonsexual, are amenable to change, like purely aversive disgust reactions. Examples about of bigots forsaking their bigotry, which is often reinforced through a feeling of disgust; but many other examples like treatment for extreme phobias, or just getting used to something that used to gross you out (like parents changing dirty diapers), also exist. It seems much easier to change what we hate than change what we like.

Some people, implicitly or explicitly, seem to believe all visceral reactions are rooted in considered (or consider-able) beliefs: that if you are afraid of getting fat, you are on some level fatphobic, and with enough self-reflection identifying and working through that phobia, your fear will dissipate. I don’t think that’s true, and I have two competing hypotheses why. One, for fatphobia (and beauty standards generally; and also possibly some elements of sexuality), we are subject to some system within our brains that really is deeply rooted in early experiences and is primitive to other systems for social interaction built on top of it; the fact that sexuality and beauty standards are inescapably of the body is not a coincidence, because judgement of the body is important even to relatively dumb primates. It helps to judge what is your species and what is not, for instance! Or two, it’s about the positive attachments thing: there are positive rewards (again, even if only internal) we learn to associate with actions even if they are unpleasant in the moment. We abstain from food; we feel hungry, but virtuous. The bridge in this hypothesis between beauty standards and sex is that both are about pleasure, albeit of two different kinds, whereas disgust or anger are purely aversive and thus more easily overcome.

Sexual pleasure and desire are conceptually simple, but also extremely powerful. Anybody who knows the experience of stumbling across that sex act or piece of erotica or just incidental stimulus that really does it for you, and being instantly hypercharged by arousal, can confirm this. But you know what is also powerful? Probably as powerful as sexual desire? The need for social approval and positive attention. Like sexual desire, it’s not experienced universally, but it is extremely common; people will go to insane lengths to get it; and as social animals, it’s an equally foundational element of a significant part of our cognition.

And the fact that dieting and body image and disgust toward our own or other people’s appearances is couched in moralizing terms is not a coincidence either, I suspect. Moral approval seems in many ways to be the first and strongest manifestation of our social instincts. That also makes sense: a cognitive systems centered around cooperation will probably naturally come up with something that looks like morality, and the fact that our moral reasoning arises first out of a sea of contradictory intuitions built on how we are raised and socialized, rather than reasoning from simple prior principles, is why the field of moral philosophy is so complex. Everything gets reduced to terms of moral judgement sooner or later: sex, food, money, politics, even pure aesthetics. Being able to feel positively about our own virtue is crucial to our mental health; less crucial, but still quite common, is to be able to derive pleasure from looking down on others, itself a kind of social hierarchy judgement. And while some of our gut moral judgements may rest on disgust, some do not; it is easier for me to imagine someone getting over a moral opposition to homosexuality than it is a moral opposition to murder, for example. Perhaps it’s not aversive reactions generally that are fragile, but only disgust, which is, after all, often openly amoral.

I don’t want to speculate too heavily on the evolutionary aspect of these psychological forces, because I think evo-psych is in practice pretty garbage, and it’s not nearly as interesting to me as how these forces actually work in our brains and our society now. We can basically stipulate our brains are evolved systems, and move on. Fundamental to cognition may not mean evolutionarily early, although I suspect it is in this case, because the basic tools of social cooperation are widely spread among animals generally and mammals in particular. And I want also to distinguish between, like, the system within the brain that gives rise to moral intuitions and reasoned-about morality, whatever the form that reasoning takes. Even if the latter exists as an enterprise only because of the former (imagine a solitary intelligent species that has no need for cooperation and thus no morality), it is still separate. I can imagine a being, say a modified human that’s a product of some mad science experiment, that lacks our gut-level moral judgements, but is still capable of reasoning about ethics, and still has empathy and higher-level moral values. In some ways, they might be more rational than us on certain moral matters, because they have fewer entrenched biases, and no immediately conflicting intuitions they must overcome.

But of those most entrenched, circumstantially-conditioned gut reactions, like beauty standards, is this something within ourselves it is genuinely possible to change? Or can we only reach an awkward detente with them, like an impossible-to-realize kink? I wonder sometimes what a world in which we could make ourselves look however we wanted would be like; but equally interesting perhaps would be a world where we could make ourselves like whatever we wanted. A world where you could choose to find anyone (or everyone!) intuitively beautiful would be fascinating!

#interesting#long post#psychology#attraction#bias#kink#neurology#beauty#beauty standards#morals#ethics#sexuality#philosophy#moral philosophy#socialization#positive feedback#sexual preference#body image#cognitive#social animals#sexual desire

108 notes

·

View notes