Photo

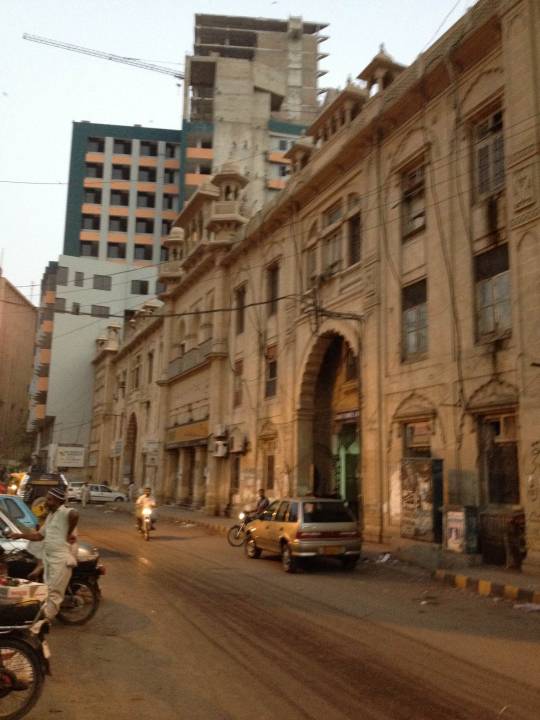

From Saturday walk:

Saturday 7th June 2014. Walk to think Or Walk to Not think.

Second of the weekly walks: Further west on M.A. Jinnah Road. Boulton Market, Jodia Bazar and Sarafa Bazar, parts of Mithadar.

Photo Credits: BT.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

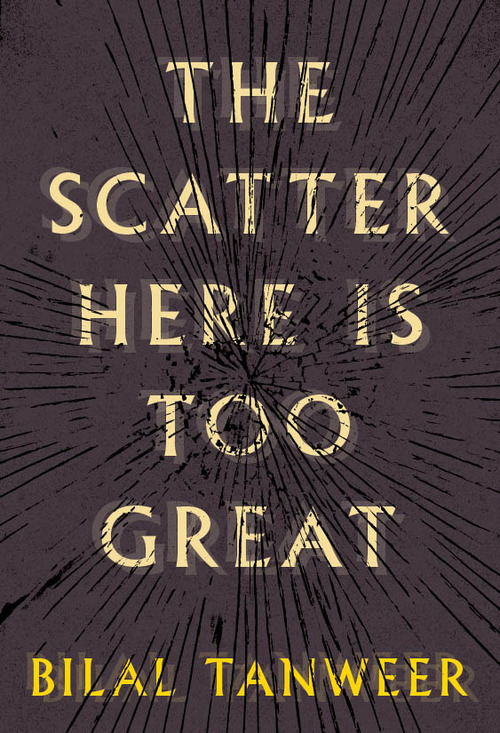

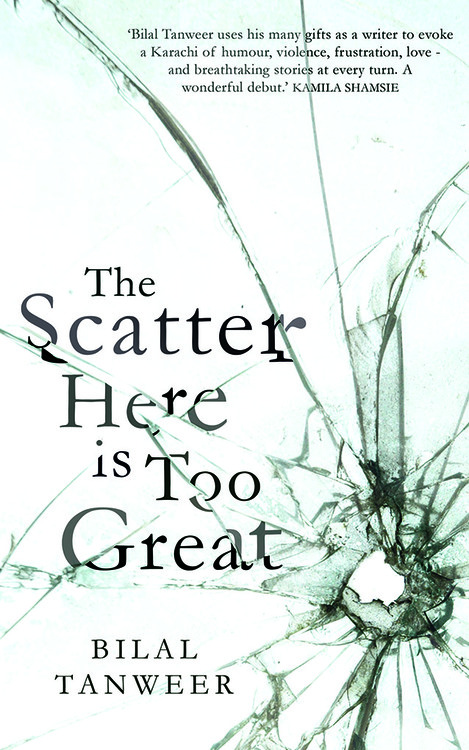

One of the best things about books is the book jacket

I probably should have shared these earlier. Not entirely late though. The US (HarperCollins), UK (Jonathan Cape), and France (no cover yet) editions come out in August 2014. The brown one is the Indian Subcontinent edition (Vintage/Random House India) which came out last December. Good things have been said. Should I post a post regarding the reviews? Maybe.

HarperCollins, North America cover:

Jonathan Cape, UK cover:

The Random House India, Indian Subcontinent cover:

2 notes

·

View notes

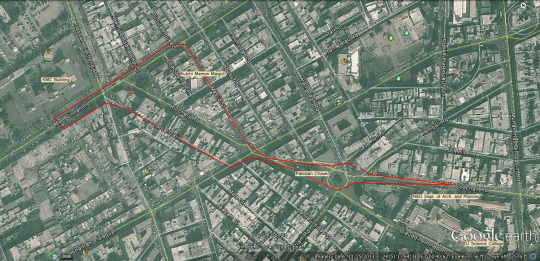

Photo

Some glimpses from my walk today.

Saturday 31st May 2014. Inroads.

First of weekly strolls in old Karachi. Androon Sheher (Inner City)

Photo Credit: BT the great.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

I wrote a little "Year ender" piece for The Express Tribune talking about things that I found hard and those I thought were hopeful in Pakistan. Nothing special but give it a go. I mention: the development paradigm in place, Mohammed Hanif's pamphlet on the missing Baloch, Dhinak Dhinak by Beygairat Brigade, Habib University, Women.

2013 seems to be the year where I had to exert myself ever harder to convince myself that things really were normal.

But as things go, it all wore thin pretty quickly because it was pretty hard to shrug off the fact that one’s illusion of stability and normality clearly does not suit a vast number of people in this country who consider themselves—or wish to consider themselves—citizens of this country. Here I list three things that were reminders of our collective failures in 2013, and two things that beaconed real hope that we can take with us into the year 2014.

[Click on the header to read more. Happy New Year.]

0 notes

Text

Sarmad Sehbai

[I was asked by the wonderful people at The Herald, Karachi: "Who is Pakistan's Greatest [Living] Poet?" Obviously, I told them, I have not a blasted clue. But they insisted. So I wrote something on my favorite contemporary poet in Urdu.]

An honest answer to this question is that I do not know. Neither do I consider myself the person capable of doing justice to a question like this one. I am a dilettante of poetry in two languages that I have studied unsystematically without paying much attention to their chronological developments or evolution, glimpsing the canon here and there, but mostly just skipping about vast lyric fields like a scamp unschooled in the frippery and finery of appreciation. Of course, there is no pride in this, but an admittance of my limitations as a reader, and in this case, as a commentator: poetry I have read hardly ever from my brain, but from my gut: I have followed whatever enticed me and in no particular order: Faiz, Rashed, Majeed Amjad, Nasir Kazmi, Ghalib, Mir, Firaq, and, of the more contemporary poets, Sarmad Sehbai.

Describe Sarmad Sehbai’s poetry and you would find yourself reaching down to words clustered around the erotics of human desire: sensual, sensuous, luscious, carnal, alluring, amorous. The attitude that Sarmad Sehbai’s poetry articulates—between the self and the world, experience and its awareness, between one human and another—passes through the dark channels of the human body. His achievement in a small oeuvre (two published volumes of poetry—Neeli ke Sau Rang and Pal Bhar ka Bahisht,plus one, Mah-e Urya’n which is forthcoming) is that he has not only discovered a language and imagery entirely his own but he is thoroughly committed to servicing the world through it.

Nietzsche writes somewhere that the artist “can only remain with his gaze fixed on what is still hidden in the unveiling.” In Sarmad Sehbai’s poetry, the revelation of the body serves only to deepen its mystery. Many of his poems of varying subjects mirror the movement of the orgasm and end with registering the ‘emptiness’ of coming into deep but ephemeral contact with an elemental force, a mysterious darkness, a recognition of a power residing in each one of us that is greater than all of us. (This excludes the ghazals, of course, where the form dictates the movement, and the thought is mostly fragmentary.)

Great writing reacquaints us with a familiar, worn-out world. After one reads Sarmad Sehbai’s poetry, the world appears again, deeply in touch with itself, in a sudden blooming of awareness of its own body's power and mystery. I would be hard-pressed to find another poet who does the same for me with such intensity.

Originally published in The Herald, November, 2013

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

On the Map: IWP Interview

While at the International Writers Program residency in Iowa (iwp.uiowa.edu), the good folks there did a little interview with me and talked about life, writing and other good things. It's fun.

0 notes

Text

Stories of Sarmad By Bilal Tanweer

I wrote this essay some 3 years ago when I discovered there was nothing decent on Sarmad on the web. It is nothing great (and I am tempted to edit large swathes of it as I reread it) but I hope it provokes some important conversations.

The original essay that appeared in Dawn, Books & Authors can be accessed here. Please note there was an error in the original article regarding the date of Sarmad's death (it's 1659-1660 CE not 1670 CE). It has been fixed in this version.

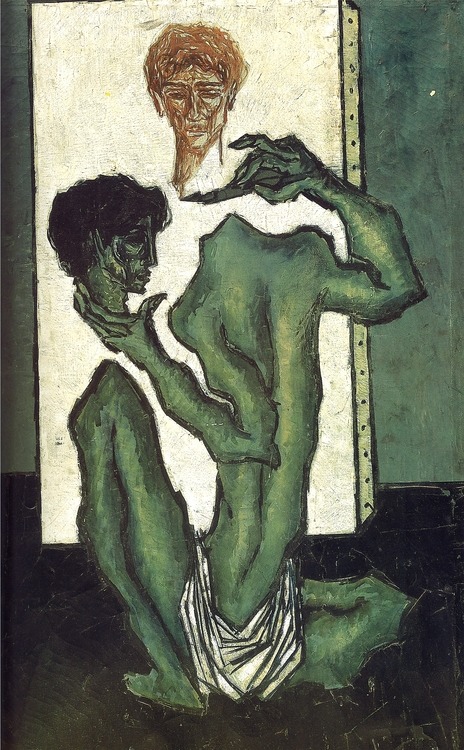

Among recurring motifs in Sadequain’s work is the image of a headless man holding his lopped head in his hand. The dislodged head, sitting on the palm of the man’s hand, is studying a beloved subject (e.g. a nude woman), while the other hand sketches the subject on canvas. In another variation of this motif, the severed head is looking back at the vacant spot, while the brush is drawing the self-portrait of the head in blood. In all these versions, the lopped head is an unmistakable symbol of ecstatic transcendence: the head is dismembered from the body but is reunited in the subject, in the act of creation, in the contemplation of the beloved.

But whose head is this?

This is Sarmad’s head. This head was lopped off on Aurangzeb Alamgir’s orders in the compound of Jama Masjid Delhi. It survived history’s amnesia by turning its owner into a fountainhead of stories and myths. But despite Sadequain’s reclamation, Sarmad remains a forgotten figure.

While it may be useful for scholarly research to separate the historical person from stories, this methodology refuses to serve us in introducing Sarmad. This is because the Sarmad who resides in our cultural consciousness is an archetype; his historical person cannot be separated from the fictitious and fantastic stories associated with him. Besides, if we separate his various images competing for primacy (including ones arising out of improbable stories), it would also run the risk of making this problematic figure simplistic.

Sarmad is problematic mainly because of the paucity of primary accounts on his life and works. He is claimed by all religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Hinduism) and each has narratives to support its claims – no matter how outlandish. One historian, Nathan Katz, has gone to the extent of counting the number of ruba’iyat in which Sarmad has expressed disdain for each religion (he finds eight ‘against’ Islam; seven against Hinduism; and only one against Judaism). But in all the accounts, there is one predominant defining feature: Sarmad’s life is portrayed as a symbol of the vibrant Indian religious syncretism at odds with the puritanical interpretations of religion. The resulting story runs something like this: Sarmad is the mystic who roamed the streets of Delhi without clothes. His mortal enemy is the bigoted king, Aurangzeb Alamgir, and his coterie of accomplices, the scholars of his court, who, for reasons of professional jealousy, crave that Sarmad be put to the sword. Almost all biographical accounts of Sarmad’s life glorify him as an example of religious tolerance while Aurangzeb symbolizes the ‘intolerant religious orthodoxy’. And while this might be useful to propagate a certain viewpoint on religion and politics, it irreparably obscures Sarmad’s life for us.

Therefore, while being mindful of the limitation of the discourse out of which these stories arise, for the purposes of this sketch, meant as an introduction to this figure, we will treat Sarmad the mystic, Sarmad the poet, Sarmad the historical person, Sarmad the mythical figure who performed miracles, Sarmad the legend, and Sarmad the scholar as one and the same.

Sarmad’s life, as it comes to us, is a collection of a few facts connected by a multiplicity of fantastic stories. Any account of his life can offer little if it does not present these stories as the story of his life.

We will start with the facts, by which is meant events common to most accounts of his life.

Almost all reports of his life agree that Sarmad was born to an Armenian Jewish family in Kashan, Persia. His date of birth is not clear; most recent scholars tentatively put it at 1590 CE, though there are claims for a range of dates between 1590 till 1618 CE. While still in Iran, Sarmad mastered the Judaic texts and moved to study with famous Muslim scholars and later converted to Islam. Abul Kalam Azad, in his essay on Sarmad, states that Sarmad’s knowledge and understanding, especially of Arabic, was at darja-e kamal – the level of excellence. According to a number of accounts, Sarmad’s adopted Muslim name was Muhammad Sa’id.

Sarmad came to India, arriving at the port city of Thatta as a merchant in 1631. There he fell in love with a Hindu boy, Abhai Chand, who became his constant companion. All accounts present his love for Abhai as the factor that made him renounce the world. Under Sarmad’s tutelage Abhai learnt Arabic, Persian, and Hebrew and eventually, under Sarmad’s supervision, translated some parts of the Torah into Persian. Sarmad’s wanderings took him from Lahore to Hyderabad Deccan until he landed finally in Delhi where he was already famous as a mystic of great powers.

In Delhi, Sarmad became a companion of the famous sheikh, Syed Hare Bhare. The other important event was his contact with the Mughal prince, Dara Shikoh, who became his devoted disciple. Sarmad famously predicted that Dara would succeed Shahjahan as the successor to the Mughal throne. This did not turn out to be true, and soon afterward, Aurangzeb claimed the throne and had Dara executed. When Sarmad’s critics pointed this to him, he remarked: Che kunam? Shitan qawi ast (“What can I do? Satan is powerful!”). In another tradition, Sarmad claimed that he had predicted the kingdom of the hereafter for Dara.

Sarmad’s is commonly portrayed as being notoriously intolerable of authority. Among those he routinely refused to show respect to was the Emperor himself. Legends have it that Aurangzeb was deeply annoyed by Sarmad’s nudity. Once as Aurangzeb’s procession was passing through the streets of Delhi, he saw Sarmad sitting by the roadside. The kind ordered the march to halt and demanded the mystic to cover himself. The saint looked at him with wrathful eyes and said, “If you think I need to cover my nudity so badly, why don’t you cover me yourself?” When the Emperor lifted the blanket lying on Sarmad’s side, he saw the bloodied heads of all the family members the emperor had had secretly murdered. Bewildered, Aurangzeb looked at Sarmad, who said, “Now tell me, what should I cover – your sins or my thighs?”

It is highly improbable that an Emperor tried to cover a naked fakir with his own hands, but such stories are good examples of the spirit and viewpoint which shape the portrayal of Sarmad and Aurangzeb’s supposed encounters.

In another such story, Emperor Aurangzeb’s daughter, Princess Zebunnisa, saw Sarmad making clay houses on the roadside. After paying her respects, she inquired: “Are these for sale?”

“Yes,” Sarmad said, “I will sell them for some tobacco.”

Upon receiving the tobacco, Sarmad wrote around the border of one of the clay houses: This clay house is sold to Princess Zebunnisa for some tobacco. That night Emperor Aurangzeb saw a dream. He was roaming around in Paradise, when he saw a beautiful palace. When he approached it, he was barred from entering it. Then he noticed that the palace had Princess Zebunnisa’s name written on it.

An age has passed since Mansur's fame has grown ancient

I will figure forth anew the noose's wine.

Sarmad is remembered most of all by the manner of his execution, which took place in 1659-1660 CE. The charges against him are not clear. His minor offences included his public nakedness, use of bhang (marijuana) and his homosexual affair with Abhai Chand. But these were not enough ground for execution and some accounts actually mention Aurangzeb himself pointing this out. However, Sarmad’s main offense was not reciting the full kalima and claiming that Prophet Muhammad did not ascend the heavens, but that the heavens descended to Muhammad. The religious scholars of Aurangzeb’s court pronounced him a heretic and convinced Aurangzeb to carry out the execution as a binding religious duty.

Sarmad had refused, even under duress, to recite the full kalima. Instead of reciting: There is no God but God, and Mohammad is the messenger of God, he insisted on stopping short: There is no God. When asked the reason for this, he plainly stated that this was the stage he had reached in his spiritual journey and he would be lying if he said more.

When Sarmad was beheaded, his body seized the lopped head from the ground and ran up the stairs of Jama Masjid threatening to destroy Aurangzeb’s kingdom. In another version of the same incident, the moment Sarmad’s head was severed from the body, it fell to the ground and everyone in the audience heard and saw it recite the full kalima.

A word about Sarmad the poet, and the literature available on him in Urdu. Sarmad was an accomplished Farsi ruba’i poet and while there is dispute about the number of ruba’iyat associated with him, the number ranges between 320 and 340. A critical edition of his ruba’iyat does not exist. In 2007, Muhammad Saleemur Rahman (Nigarshat Publishers, Lahore) published a collection of his ruba’iyat, Ruba’iyat-e Sarmad, which also contains his prose translations in Urdu. The translations are fairly accurate and true to Farsi originals. Another work in Urdu is by Arsh Malsiyani, Naghma-e Sarmad (Markaz-e Tasnif-o Talif, Nakodar: 1964). These are poetic renditions of Sarmad’s ruba’iyat in Urdu.

The author is a graduate student at Columbia University, New York. [email protected]

Sadequain image reproduction acknowledgement: SADEQUAIN Foundation, San Diego

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varieties of Obligation By Bilal Tanweer

REVIEW ESSAY

Ghanti (Short Stories) by Nilofar Iqbal

Surkh Dhabbay (Short Stories) by Nilofar Iqbal

The fools in Nilofar Iqbal’s stories are mostly men. They are either cuckolds or cheaters; obsequious and considerate or uncaring and indifferent. But that’s not a complaint or weakness. These predictable, two-dimensional male characters vacate the stage to allow her women to come in full view and enact their needs and frustrations. And Nilofar Iqbal’s women are completely wonderful: they are deeply conflicted about the demands placed upon them by the world; often they are unsure and insecure, but that’s because they are intensely connected with their bodies and conscious of what they want and how—and best of all, they know how to work all them foolish men to their ends.

Reading her two collections of stories, Ghanti and Surkh Dhabbay,her standout characters are women who are go-getters: Miss Romana who is such a thorough professional when it comes to her work that Qadeer sahib, her boss, a middle-aged man with a family and oppressive wife, is left mostly confused when she starts showing up for work in gauzy kurtas that reveal the her lingerie that matches the color of her handbags. Raufa is another one—a thirty-eight year old who is living in a rented single-room but having a good time with Peji—Pervez—a freshman in college, who, in return for his love and attention, is milking Raufa for money and expensive gifts. Raufa perhaps is Nilofar Iqbal’s strongest creation—a tragic character who is so impaired by her needs that she’s blind to what’s ironically apparent to the readers all the way through. Her triumph and tragedy lies precisely in the agency and choice she exercises in a society that constrains women in all number of ways but most obviously in their choice of partners.

The real subject in Nilofar Iqbal’s fiction however is families. Her dramatic project is set around examining how people negotiate their needs and dependencies within the demands of the family. A repeated story that recurs in different permutations throughout her collections deals with a dying family member, and how the pressures and obligations of his dependency (it is a He every single time) are taken by the rest of the family. It results in some of her best work: In Ghanti, for instance,we are taken close to the loneliness of a dying father who has been shifted upstairs in the house and has been handed a bell that he must ring to call for assistance. He misses the familiarity of his old room, where he has spent fifteen years, and the fact that he needs assistance for the smallest things like using toilet and turning in his bed. Nilofar Iqbal meticulously explores the effect this man’s sickness has on each member of the family: the wife’s social life eviscerates; the children desist from going near the sick man; the son resents everybody for ignoring his father but then gradually begins to feel the tyranny of obligation of being at his father’s beck and call at all times—even at night.

Indeed, the keyword that defines Nilofar Iqbal’s families is Obligation. Her families are a nucleus of unhappy people united by obligation and who, knowingly or unknowingly, inflict harm upon each other for their own needs: a mother refuses to marry her overage daughter because she’s terrified of being left alone;a father beats up a child for refusing to give up school and take up a job at the zamindar’s who is his employer, who might fire him if his boy doesn’t turn up for work; a cuckolded husband feels obligated not to confront his cheating wife in the presence of his son-in-law; an old wife is obligated to take care of her sick husband and put up with ungrateful children—obligation in its varieties is the primary source of drama in Nilofar Iqbal’s stories.

Not all of her stories succeed. Many stories feel abandoned at the point where conflict is ripe for explosion and characters are prepared for drastic action. It happens more often in her latest collection Surkh Dhabbay, where most stories feel like rough sketches rather than fully executed stories: Fatah, Crystal House, Musalman, Mera Dost Mujahid, Dilip Kumar, Chooha, Operation Mice. These stories are exciting in setup but disappointing in their denouement and eventual realization. Chooha is the story of a man sprawling and kicking in the pits of despair, who eventually goes underground (literally, figuratively) without much consequence or drama. In Crystal House a couple who have collected valuable crystal from around the world in their house die one day and their crystal is, well, auctioned quickly and readily by their children. In Dilip Kumar a servant with a talent for mimicking Bollywood is thrown out of the house and nothing much happens thereafter. Her most ambitious story in her new collection, and perhaps her most admirable failure, is Operation Mice where she explores the War on Terror from four different perspectives: an American army general, his wife, their son on a mission in Iraq, and his fiance who is waiting for him back home. The story is predictable and ends predictably staying within the comfortable confines of the received wisdom about the human costs of war, but it also a drastic break from all her other work and for that reason, it represents a laudable risk.

Nilofar Iqbal’s finest story in these two collections is Chaabi where the protagonist, Abida—summed up in the very first line of the story rather discordantly as: abida chai ki aisee piyalee thee jo rakhay rakhay thandee ho ga’yee thee—after getting disappointed with her family and friends and becoming wholly indifferent to herself and her needs, finds a moment of transformation. It’s a story that’s deeply reminiscent of one of Chekhov’s best stories, The Kiss. It maps the changes in Abida when she hears that a good looking youth has come to reside in the house-next-door, which is connected to her room with a padlocked window beneath which there is enough space for her hands to slide into her neighbor’s territory. One day she puts her hand in the window and pulls the handkerchief of the man she has come to long for. She’s disappointed with the ordinariness of the handkerchief, its lack of any romantic clues for her, and its harsh smell of tobacco. But as she’s replacing it back in her neighbor’s window, her hands are pinned down with the rough hands of a man she’s never seen. She quickly pulls back her hand, but this physical contact sets in motion small changes that alter her relationship to herself, her body, and the world. It’s a beautiful, gem of a story—and ends on a less bleak note than Chekhov’s.

Her latest collection of stories, Surkh Dhabbay, does not fulfill the promise of her widely hailed debut. At least, not yet. However, the best stories in her oeuvre do hit the beat and thrum of the world we know—and wish we understood. They help us understand, and yield enormous pleasures.

Bilal Tanweer is a writer and translator. He was recently named an Honorary Fellow of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. He teaches at LUMS.

This essay was first published in Dawn, Books & Authors – February 10, 2013

0 notes

Text

Coke Studio by Bilal Tanweer

This essay originally appeared in Critical Muslim Vol. 4 (Hurst & Co. London: 2012. eds. Ziauddin Sardar, Robin Yassin-Kassab).

There are no billboards on the streets. For the last four years, a week or so before the new season of Coke Studio is launched, most of the important billboards in major Pakistani cities are taken up by snazzy advertisements announcing the featured artists of the season. It’s the biggest annual ad campaign for any TV program and this is Season 5. It’s being touted by many to be the mother of all seasons, mainly on the basis of a wildly circulating promotional video of Episode 1 of the new season. The first artist on the promo video is a rapper: Bohemia. The video shows him in a hoodie and dark glasses, slamming out a rap number in Punjabi. ‘This is an opportunity for me to tell you what rap is—it's poetry, it's a message,’ he says in a close-up shot of his 3-second interview. The video cuts back to the song. By his side are the Viccaji sisters - Zoe and Rachel - who do backing vocals and harmonies but they appear to be in a more prominent role for this number.

The clip is followed by Hadiqa Kiyani, among Pakistan's leading female vocalists, singing what sounds like the hard rock version of an AR Rahman's composition. She is singing the Sufi poetry of Bulleh Shah. She’s followed by Atif Aslam, arguably Pakistan's biggest rock star, also a sensation in India for the last four years. He has teamed up with ‘Qayaas’, an underground band, to do a version of a Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan qawwali. The last singer on the promo is of Humayun Khan's who is singing Larsha Pekhawar Ta, a popular Pushto folk song.

The absence of billboards is unexpected. For the last three years or so, Coke Studio is the soft drink brand's main marketing strategy in the country. In fact, the entire marketing campaign of Coca Cola Pakistan is designed around Coke Studio: artists featured in the program are on Coke bottles, cans, television adverts, newspapers, television, radio and billboards. But there is no visual clue of it this year. Maybe it is a scaling back by the soft drink company. But the other interesting thing I notice is that on Coke Studio’s Season 5 website there is no ‘About’ tab either - meaning nothing to introduce a newcomer to Coke Studio. Taken together, these could mean a number of things, but they unmistakably do mean that no one needs to be told What Coke Studio Is and What It Does; and second, nobody needs reminding that Coke Studio will start airing on May 13. It’s common knowledge.

In other words, if there is a confirmation of Coke Studio's status as a cultural behemoth in Pakistan, this is it.

Music Channel Charts (MCC), 1990

Coke Studio is a world apart from Music Channel Charts, the programme I grew up on, and where I first encountered rap.

The song was called Bhangra Rap, a mix of Punjabi bhangra with rap. The lyrics were a smooth and unselfconscious mix of Urdu, Punjabi and English. The song was sung by a young man, Fakhr-e Alam, who in the music video sported a huge locket with a Peace sign and danced some serious moves in his baggy, torn-knee jeans. My younger brother and I loved Fakhr-e Alam and his music and everything about him. We had memorized Bhagra Rap by heart and sung it in chorus with friends.

Growing up in the nineties, our entertainment options were limited to street cricket and two TV channels - a private one and a state-owned one. The transmission time for both channels were around eight to twelve hours a day and almost everyone we knew had memorized the entire week's TV schedule. MCC aired on the private TV channel, NTM (later renamed STN), and featured young men (all of them men, except for a handful of female vocalists in a few scattered exceptions) who looked like creatures from another planet compared to everything else on TV: They had unsuitably long hair, wore chains around their necks, jeans that were either tight or torn and their music was loud and brash. These boys made my middle-class parents deeply uncomfortable, for, they projected an image which was perhaps my parents' very worst nightmare. For them, these boys were of an age where they should’ve been worrying about jobs and earning a livelihood. Instead they were running after girls on their bikes and making sounds in the name of music that positively punished my parents’ sensibilities.

My brother and I, on the other hand, loved everything about this programme. It was decidedly different in its energy, sound and look from everything else we had seen on TV. It lacked polish but we hardly cared. Almost all the videos were cheaply recorded and produced at home by amateurs. The videos were all shot around predictable locations like garages and apartment rooftops and the Karachi beach makes an obligatory appearance in most of them. Not surprisingly, most of them were shot during the day too (lighting/studio services being too expensive).

My mother would sit and monitor us as we watched the show. When we got too excited (which happened often when our favourite band/number was ascending the charts), she would disapprovingly start pointing out everything that was wild and uncivilized: ‘Look at the way this boy is jumping. Baboon. Look what he's wearing. I bet he got that from the flea market.’ The jibe that stung most: ‘Look how this boy is aping the firangis (westerners); seems like he's smelled some white man's knickers.’ We had little choice but to ignore her taunts and focus squarely on the music.

MCC was a ground breaker. Its competitive format drew legions of followers and encouraged hundreds of young men to make their own music videos. Despite its limited production values, MCC was an astounding success. During the four years it ran, MCC introduced many young musicians who went on to define Pakistani pop music: Ali Haider, Nadeem Jafri, Fakhr-e-Alam, Saleem Javed, Amir Zaki, Strings, Junoon, Amir Saleem, Bunny, Khalid Anum and many others. MCC also redefined the way the Pakistani urban youth imagined themselves. One of its major bands, ‘Vital Signs’, became a major force on the pop scene in Pakistan.

MCC disappeared almost as suddenly as it had appeared. As cable television penetrated Pakistani cities, local television lost viewership and the audience switched to MTV, Channel V and Bollywood music in a big way. MCC closed shop in 1994. By then, Pakistan already had a nascent but confident pop music scene, a maturing concert circuit and sponsors willing to foot the bill.

Coke Studio, 2012

A lot has changed in Pakistan since. The country has become polarized along ethnicity, religion and class. The contradictions and ideological confusions of the nation are also reflected on the pop scene. One of the country's biggest pop star, Junaid Jamshed of ‘Vital Signs’, abandoned music, embraced the life of a religious preacher of the evangelical Tableeghi Jamat, grew an luscious long beard and established his own a fashion label. Ali Azmat, ex-vocalist of the most successful Pakistani rock band, ‘Junoon’, became a conspiracy theorist who blames ‘Western and Hindu Zionists’ for all the ills of the country, holds the US responsible for funding terrorism in Pakistan, prophesizes that Pakistan will transform in the near future into the military bastion of all the Islamic countries, and idolizes the Pakistani military as God's gift to the Muslim world. Then there is Najam Shiraz who made his debut on MCC, and who now sings moving na'ats (religious devotion songs) alongside his standard pop output. There are a number of soft and hard, red and white revolutionary bands. One band, ‘Laal’ (literally, Red) espouses Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist ideology and sings revolutionary poets like Habib Jalib. There are others like Shehzad Roy and Strings, who sing of economic prosperity, law and security, and education for all and wish to see a culturally liberal and economically viable Pakistan, integrated in the world economy. In other words, Pakistan's cultural imagination is as fractured both vertically across classes and horizontally across ethnicity and ideology as the nation itself. There seem to be few instances where art could transcend these rigid boundaries.

Coke Studio emerged, as a clear attempt to bridge the cultural fragmentation of Pakistan, against this background. The first episode of the first season was aired on 8 June 2008. Broadcast on a number of television channels, with Video and MP3 files available for immediate download from its official channel on YouTube, it received instant critical and popular acclaim. The show’s accent was firmly on bringing tradition and modernity together in a new synthesis. It made a conscious and sustained effort to work out a way to engage with the traditional folk music of the Subcontinent using the vocabulary of Western music, which is more accessible and familiar to the younger audience. Through Coke Studio many folk musicians and their work has been introduced to a new generation and allowed them to access a deep and rich cultural heritage that was withering on the margins.

The young filmmaker and blogger Ahmer Naqvi was swept off his feet when he first saw Coke Studio. ‘We all grew up as Junoonis and Vital Signs fans. There was little else that was available culturally to us as young Pakistanis’, he says. He, and countless young men and women of his generation, grew up with only a vague sense of the traditional music of their region. ‘Coke Studio grabbed us because it was an amalgamation of things that were already present in our subconscious and all around us, but we never really paid attention to them,’ says Safieh Shah, who wrote a detailed comment on every Coke Studio episode in the last season in The Friday Times. ‘Coke Studio not only brought all those things together but did it in a way that was accessible to us’. Aamer Ahmad, who was the recording engineer on Season 2, the season where Coke Studio found its feet and gained popularity as the cutting-edge of Pakistani music, concurs. ‘Coke Studio provides people a platform where they can come to talk, chill, relax. It's like when you put a dhol wala, a drummer, and a guitar player in a room and they automatically make music. Because that's what they do’.

Rohail Hyatt

To understand Coke Studio we need to appreciate Rohail Hyatt, the producer and the driving force behind the show. Hyatt was a founding member, producer, song writer, guitarist and keyboardist of ‘Vital Signs’. The band was formed in 1986 and exploded onto the Pakistani music scene with Dil Dil Pakistan,one of the most popular songs the music history of Pakistan. It became, and continues to be, the pop national anthem of the country. In a 2003 BBC poll of the ten most famous songs of all time, Dil Dil Pakistan ranked third. Vital Signs also scored two important firsts in Pakistani pop history: they were the first local band to land a major sponsorship deal (Pepsi) and the first to tour the United States. The band also did a number of cross-country tours, a rare achievement. Vital Signs broke up in 1998. Rohail joined the advertising industry until he returned to music with Coke Studio ten years later.

Hyatt is a naturally shy person whose dislike for interviews is well-known. Not surprisingly, he did not respond to my multiple requests for an interview. However, in an interview for Dawn, he stated that when he stumbled into classical music a year before Coke Studio, ‘I was pretty blown away by the fact that here I was, a musician all my life, and I had no idea about a treasure of an art form that we had and it was so different from the western music that we had grown up with’. He felt that ‘we as a people needed to experience our heritage, so this stems from one small experience into discovery’. Hyatt, says Haniya of the singing duo Zeb & Haniya, ‘has very distinct likes and dislikes. His aesthetic met the traditional music of Pakistan—and something clicked’.

In Coke Studio, Hyatt focussed on two specifics: a. production quality, and b. freedom for the artists to experiment without commercial pressures,. ‘Right from its inception’, says Louis Jerry Pinto, who is better known as Gumby and is considered to be Pakistan's finest drummer, we wanted to ‘have better production values and quality sound’. The high productions values are there to be seen. Indeed, television advertisements and a few music videos aside, one has not seen a television production of such visual quality and sophistication on local TV channels.

Gumby, who has been a core member of the Coke Studio house band from the first season, says that the producers decided to be flexible in both approach and outcome. ‘We said to each other to let's keep it open-ended and let’s not give it a label’. Pakistani artists have frequently complained about commercial pressures, which have stalled their creativity. Hyatt has spoken about this himself. ‘As an artist’, he told Dawn, ‘I know during the times of Vital Signs… every time we wanted to do what we really wanted to do, there was somebody telling us that “no one is going to listen to this”. It always used to be a really weird thing to give in to – my creative expression [to corporate sponsors or record labels]’.

Music à la Coke Studio

The artists who have performed on Coke Studio wax lyrical about the creative freedom it provides. The ‘beauty’ of Coke Studio, says Tina Sani, a renowned ghazal singer who performed to great acclaim in Season 4, ‘is Rohail's openness. Nobody was thinking of the commercial aspect or the audience. Rohail only suggests and you as the artist have the free-hand.’ Quite a contrast with the commercial TV channels that dominate the airwaves now where ratings dictate everything, Sani says. Muazzam, one half of the Rizwan-Muazzam Qawwal Group, concurs. ‘One thing we appreciated about Coke Studio is its environment,’ he says. The duo belongs to the Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan's qawwal gharana (extended family), and their rendition of the traditional qawwali, Nayna de Aakhay was one of the big hits of Season 3. ‘It works because people at Coke Studio understandmusic. No matter who you are, you are dealt with on your own terms. You are not bound in any way or forced to think in a certain way. This kind of respect boosts the artist's confidence. We have collaborated many times internationally and have also toured around the world. But this is the best collaborative experience we've ever had’, says Muazzam.

‘We had a lot of freedom in choosing our songs and even the arrangements,’ says Haniya. ‘It is a very collaborative process. You can be as involved or uninvolved as you like.’ The degree of involvement depends on the artist. But it seems that those who are able to harness the qualities of the Coke Studio house band flourish the most. Big bands tend not to do too well in Coke Studio. The major hits have come when individual artists have paired up to exploit the genius and the quality of the Coke Studio house band which comprises some of the best musicians in Pakistan.

The process that Coke Studio follows in making its music was outlined in a video released at the end of Season 4. It describes the production process of a qawwali which was one of the highlights of the season. It starts with the invited artists doing a raw recording of the song they wish to perform. A number of other steps follow where the percussionists work out the rhythm structure and align it with the Western rhythm structure. Once the rhythms and beats are agreed, the house band gets involved and finds ways to retain the core improvisational aspect of Eastern music and works out a structure that could allow the two to function together. Finally, everyone rehearses together to produce the finished song.

While Coke Studio pays remuneration to artists, the immediate financial gains for appearing on the show are limited. But it does offer something that promises bigger financial rewards: exposure. Artists who do well on Coke Studio gain a global audience for their work. ‘Coke Studio has put us on the map,’ says Zeb of Zeb & Haniya. ‘We went to France and were surprised to find people singing our songs.’ Zeb & Haniya broke onto the Pakistani music scene in 2008 with their album, Chup - an instant hit. But their rise to international stardom came after they performed on Coke Studio in 2009. In India especially, where Coke Studio has a huge following, Zeb & Haniya performed extensively and went on to collaborate with Indian artists.

Global exposure is life blood for Pakistani artists. Making a viable living from local royalties has never been an option for musicians in the country. Indeed, many folk singers live in abject poverty. The celebrated Zarsanga, 65, who is considered the Queen of Pashto folk music, was forced to live in a tent on the roadside in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province after her house was washed away in the 2010 floods. Even mainstream singers such as the celebrated Mahdi Hassan, known as ‘King of Ghazals’, faces hardship to pay for his medical care. Part of the problem is the rampant piracy that undermines the royalties of the artists. According to an artist interview, in the 1980s, an estimated 30 copies were pirated for every original cassette sold in the local market. Twenty five years on, with the digitization of music and the advent of Internet, the entire business model of record labels has been comprehensively defeated in Pakistan. Even concert performances, which were the most significant source of income left for the artists, have suffered a serious setback in the deteriorating security situation. Now the few concerts that happen, happen indoors.

Coke Studio provides international exposure and serves as the flag-bearer of the enigmatic and creative side of Pakistan. ‘I see Coke Studio as a platform. A big platform for the artists, especially for those who are not in the mainstream’, says Muazzam. Coke studio also helps with engagements in the local circuits. Salman Albert, a guitarist for the rock band ‘Entity Paradigm’, says ‘exposure to the Western and Indian market is definitely there but even locally, after Coke Studio one gets many more concerts.’

But not everyone agrees that an appearance on Coke Studio would automatically lead to financial rewards. ‘Coke Studio has not enabled any artist to make money off music, and it does little other than providing fame, which helps them get more concerts’, says Fasi Zaka, broadcaster and respected long-time commentator on the Pakistani cultural scene. ‘TV has always done that for the artists. But that doesn't mean it is bad. I think Coke Studio remains a great experiment in Pakistani music - mining folk influences and bringing a contemporary touch to it.’

The corporate side of Coke Studio

Zaka and the noted cultural critic Nadeem Farooq Paracha have been staunch critics of corporate sponsorship in music. ‘The problem with corporate money has been that it influences in directing the output of the artist’, says Zaka explaining his stance. ‘So socially conscious artists would have to water down their artistic output because of corporate money involved and because corporations do not wish to be associated with anything political. For example, Shehzad Roy after his single Laga Reh, suffered because no sponsor wanted to touch him due to the overtly political nature of his song.’ However, both Zaka and Paracha have now changed their views.

For Paracha the reason lies in the rise of militant Islam. ‘I have revised my earlier position because frankly speaking I wonder if we have the luxury now. The radicalization in our society has increased and nothing much is happening on the cultural front. It would be all right to criticize Coke Studio as a corporate brand game if we were an open society. To criticize Coke Studio in the present situation would be nihilistic.’ Zaka has other reasons. ‘For the music in Pakistan now, corporate money is an essential input. All the revenue streams for artists have dried up and the market isn't promoting these artists or their music. Also, with the digitization of music, corporations affecting the output of socially conscious artists have become a minor issue. Artists who have something political to say can still say it’.

The artists themselves vigorously support corporate patronage. Gumby, who has been in the industry for over fifteen years, feels strongly. ‘To critics who say it is commercial, I ask: What's your point? Everyone is commercial. If corporate sponsorship did not exist in this country there would be no music. Coke is getting brand value for this money. And over the last few years, one has seen the conservative thinking in the corporate world also change and now one sees a certain level of sincerity in their efforts too: they are genuinely interested in promoting music.’

But would Coke sponsor something that does not have the potential to be so popular, for the sake of music? ‘If some people believe that Coke is doing it for the music, that just tells you how good a spin they have managed to put on it,’ argues Zaka. ‘But ultimately, we have to judge the net effect - it's good. If their aim is to sell their product, they could also do it by buying a lot of air time and running 30-second advertisements. But if they are doing something that also benefits culture and music, then it is good.’

Coke Studio is indeed good: it is good for Pakistani music, good for our cultural heritage, good for musicians, and ultimately good for audience – music lovers all over the world. It is something, says Aamer Ahmad, ‘that we as a culture should have done sixty years ago. We should be doing it on a much larger scale, our government should be doing it’. When Coke Studio first appeared on the scene, the music industry was in the doldrums and all the music channels were losing money. ‘It’s not like they weren’t spending: they were pouring enormous amounts of money into making jingles’, says Ahmer Naqvi, who worked on Pakistan's first English TV Channel, Dawn TV.

Future of Coke Studio?

There is a broad consensus amongst the Pakistani musicians that Coke Studio has indeed become a benchmark of quality. Music production in the country will now be judged in relation to Coke Studio. But there is also an unmistakable feeling that it has become repetitive and predictable. ‘There was more creativity in the first two seasons’, says Salman Albert. ‘Now all songs have the same sound. Every song should have its own sound, music arrangement should be varied. New players should be introduced for each song. They have to do something radically new now to stay at the top’. Gumby agrees: ‘it has become predictable and people have started taking it for granted. But Rohail has a certain sound and sensibility and I have no problems with it. For me, the first two seasons were more open-ended and by the fourth season we did not have much creative input’. Perhaps this is why Gumby does not take part in Season 5; he has left for other projects providing a space for new producers to bring a fresh perspective. Tina Sani echoes similar sentiments. ‘Yes, it has become somewhat formulaic and a pattern seems to be followed. But there is no problem with it. We shouldn't be too pushy. What Coke Studio should avoid doing is chasing its own tail. Focus on making newer things. We should all encourage it.’

Such self-reflection and criticism is a good sign. Perhaps the most promising development is that Coke Studio has spurred other ideas on similar lines. Because of the unprecedented success of Coke Studio corporate sponsors now are keen to support more ventures that promote quality music. One example is Uth Records ('Uth' is pronounced 'Youth') which is sponsored by Ufone, a national mobile phone company. It is a reality show where aspiring musicians, irrespective of age and background, who have not yet released an album, are paired with industry professionals to produce a single. The show, produced by Gumby, just completed Season 2 and has received over 4,000 submissions by young musicians all over the country.

Even for artists not in music, Coke Studio serves as an inspiration. ‘As a filmmaker, it has given me the belief that somebody like me can do something new and challenging,’ says Ahmer Naqvi. ‘It has also given me confidence in the audience too. If I do something that is sophisticated, the audience is going to come up to it.’

If we judge the cultural scene in Pakistan on its own terms, the distance it has travelled from 20 years ago is heartening—given that the political instability has persisted and the country has spent every year firefighting a different sort of wildfire. The experiment called Coke Studio much like Pakistan itself continues to chart an unpredictable course forward.

More stuff:

Coke Studio Seasons are available on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/user/cokestudio

Some of the songs popular during the MCC days can be heard at: http://www.defence.pk/forums/general-images-multimedia/84235-music-channel-charts-mcc-pakistan.html

Ahmer Naqvi’s Dawn interview with Rohail Hyatt is available at:

http://dawn.com/2011/08/07/the-artist-must-shine/

and to read Safieh Shah’s The Friday Times reviews of Season 4 begin here:

http://www.thefridaytimes.com/beta/tft/article.php?issue=20110617&page=24

The Fasi Zaka and Friends Show on the Pakistan’s Radio One FM 91 is widely available on YouTube.

Pakistani pop album cover images: http://www.pakipop.com/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Artificial Fires: The Poetry of Zbigniew Herbert By Bilal Tanweer

How to describe the poetry of the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, who Seamus Heaney described as “a poet of exemplary ethical and artistic integrity in world literature in the 20th and 21st century… a poet whose work fulfills the classical expectation that great literature will delight and instruct,” and who Robert Hass referred to as "one of the most influential European poets of the last half-century, and perhaps—even more than his [Nobel Prize winning] contemporaries Czeslaw Milosz and Wislawa Szymborska—the defining Polish poet of the post-war years," and about whom Stephen Dobyns wrote in the New York Times claiming: "In a just world Mr. Herbert would have received the Nobel Prize long ago”?

I first encountered Zbigniew Herbert in a volume called Mr. Cogito and I experienced that rare exhilaration of encountering something wise, beautiful and unlike anything I had read before. It was a detached poetic voice that was also contemplative and humorous and deeply serious and yet playful all at the same time, and its sparse and precise language moved delightfully between thought and image. By the time I went through the collection, the marginalia of my copy were all exclamatory points and Wow’s of varying lengths and slants. Many of these poems have since become my ports of refuge, and one The Envoy of Mr. Cogito has grown into an anthem. However, on that first reading I dwelled longest on a much simpler poem where Herbert leads a kind of existential meditation with much lightness:

Mr. Cogito Meditates on Suffering

All attempts to remove

the so-called cup of bitterness—

by reflection

frenzied actions on behalf of homeless cats

deep breathing

religion—

failed

one must consent

gently bend the head

not wring the hands

make use of the suffering gently moderately

like an artificial limb

without false shame

but also without unnecessary pride

do not brandish the stump

over the heads of others

don't knock with the white cane

against the windows of the well-fed

drink the essence of bitter herbs

but not to the dregs

leave carefully

a few sips for the future

accept

but simultaneously

isolate within yourself

and if it is possible

create from the matter of suffering

a thing or a person

play

with it

of course

play

entertain it

very cautiously

like a sick child

forcing at last

with silly tricks

a faint

smile

Translated from the Polish by John and Bogdana Carpenter

Instead of confessing to suffering or fretting about its causes, the meditation concerns itself with a gentle prescription: to accept the suffering without resigning oneself to it; to respect it without making a spectacle of it; isolate it, and engage with it with humor and play.

Reading Herbert’s work for the first time felt like stepping into a new kind of earthly wisdom. Here was a very benevolent use of irony: to draw strength in hard times while at the same time not being delusional about the bleakness of the world. Here was a stoic courage: to battle a monstrous world without becoming a monster oneself, to always fight to see clearly, humanely instead of choosing between the convenient ideological blinders. On greater reflection, I realized that what enabled all these qualities in Herbert was his astonishingly brutal honesty: Go where those others went to the dark boundary/ for the golden fleece of nothingness your last prize. And yet:

beware however of unnecessary pride

keep looking at your clown's face in the mirror

repeat: I was called - weren't there better ones than I

beware of dryness of heart love the morning spring

the bird with an unknown name the winter oak

light on a wall the splendour of the sky

they don't need your warm breath

they are there to say: no one will console you

It is well worth remembering that Herbert lived through a dramatically oppressive time. He was born in 1924 in Lvov, Poland (now in Ukraine, Lviv) and was 15 when his hometown was annexed by the Soviet Union, an occupation that was followed by the Nazi takeover in 1941. When the Nazis were eventually defeated in World War II, his hometown was seized again by the Soviet Union.

Even though Herbert started writing poetry as a student in the 1940s, he was unable to publish any of his works due to censorship until 1956—“a period of fasting,” he described later. His struggles living and writing in two totalitarian regimes were fundamental to shaping the concerns and subjects in his poetry.

Herbert’s poems are all hard at work to free themselves from being weighed down by the world. According to Robert Hass, Herbert is "an ironist and a minimalist who writes as if it were the task of the poet, in a world full of loud lies, to say what is irreducibly true in a level voice.” His poetry relentlessly searches and strategizes for the survival of what is most gentle in us without making any false promises about life or the future of the world. His poems consider the pitfalls of language, fight battles of conscience, discuss virtue, suffering, Hell, magic, upright attitudes, and report on the temptations of Spinoza—all in a manner that is unaffected and unsentimental, ironic and humorous, but categorically against despair and wary of false hope.

Perhaps the best description of Herbert’s poetry is found in his own writing, albeit in his description of his aims in studying philosophy. In a letter to his mentor, the sage and independent philosopher, Henryk Elzenberg, dated November 2, 1951, Zbigniew Herbert said of philosophy—he began as a student of philosophy, economics, law and art history—what could wonderfully describe his poetry: “What I really look for in philosophy… I look for emotion. Powerful intellectual emotion, painful tensions between reality and abstraction, yet another rending, yet another, deeper than personal, cause for sorrow… I prefer to live through philosophy to brooding on it like hen. I would rather it be a fruitless struggle, a personal cause, something going against the order of life, than a profession.”

Actually, it is no surprise that the best description of Herbert’s poems comes from his expectations of philosophy. The search in his poems is fundamentally philosophical: he is a poet who distrusts poetry; who is painfully aware of how language gets corrupted with ideology. All his poems are attempts to arrive at clarity—even if it ultimately is only “an uncertain clarity”. He wants simple and crude truth that’s washed off the smoke and haze of propaganda and neat symmetries of ideological thinking. He’s suspicious of romanticism and loftiness of metaphor. He wants to describe the world without ‘the artificial fires of poetry’. In Herbert’s world, truth exists in simple objects. A pebble was a pebble is a pebble has been a pebble:

Pebble

The pebble

is a perfect creature

equal to itself

mindful of its limits

filled exactly

with a pebbly meaning

with a scent which does not remind one of anything

does not frighten anything away

does not arouse desire

its ardor and coldness

are just and full of dignity

I feel a heavy remorse

when I hold it in my hand

and its noble body

is permeated by false warmth

— Pebbles cannot be tamed

to the end they will look at us

with a calm and very clear eye

Translated from the Polish by Peter Dale Scott and Czeslaw Milosz

This philosophical quality also explains Mr. Cogito, the principal character in his work, the filter and conduit of his meditations. The character is a clear borrowing from Descartes, whose cogito ergo sum defined the epistemological search for certainty, a base that could serve as the foundation of reliable knowledge, for something that persists. But Herbert’s Mr. Cogito is a clumsy character, an ordinary, even less than ordinary person, who is nonetheless sharp and clear-eyed and is trying to be honest about his experience in the world.

Herbert’s search for clarity is so rigorous that he is even wary of imagination—that prized gift of the Romantics, what they held to be our Divine instrument. In a 1986 interview, Herbert remarks, “In the sphere projected by our imagination, we are always thinking that we are without limits, that our possibilities are inexhaustible, but the body is here… The body is wise.” So one should trust the body then, asks the interviewer, Renata Gorczynski. “Not permit it too much, not allow it everything, but at the same time listen to it.”

I Would Like To Describe

I would like to describe the simplest emotion

joy or sadness

but not as others do

reaching for shafts of rain or sun

I would like to describe a light

which is being born in me

but I know it does not resemble

any star

for it is not so bright

not so pure

and is uncertain

I would like to describe courage

without dragging behind me a dusty lion

and also anxiety

without shaking a glass full of water

to put it another way

I would give all metaphors

in return for one word

drawn out of my breast like a rib

for one word

contained within the boundaries

of my skin

but apparently this is not possible

and just to say - I love

I run around like mad

picking up handfuls of birds

and my tenderness

which after all is not made of water

asks the water for a face

and anger

different from fire

borrows from it

a loquacious tongue

so is blurred

so is blurred

in me

what white-haired gentlemen

separated once and for all

and said

this is the subject

and this is the object

we fall asleep

with one hand under our head

and with the other in a mound of planets

our feet abandon us

and taste the earth

with their tiny roots

which next morning

we tear out painfully

Translated from the Polish by Czeslaw Milosz and Peter Dale Scott

In a poet whose most formidable quality is his deeply cultivated negative capability, Herbert's morality stems from empathy, and an appreciation of the messiness and variedness of the human experience, and evil, from a simplification of the world. Many of Herbert’s poems feature historical villains, dictators, autocrats and despots, but they are not the crazy mad bastards we are accustomed to imagine them. Instead, they are thinkers with firm convictions on history and human nature; many of them are revolutionaries attempting to fix humanity’s maladies with ready formulas; they are people of power who consider other men’s blood a fair price for their causes, and who, inevitably, derive their power from offering their people false hope.

Herbert has been well-known through the English speaking world for many years. He was blessed with a team of two fine translators, John and Bogdana Carpenter, who translated most of his early work and championed it for many years. But for some bizarre reason, their fine original translations are all out of print now and the new translations by Alissa Valles (‘Zbigniew Herbert: Collected Poems –1956-1998’ published by Ecco Press in a beautifully produced edition) lack the lucid precision of the Bogdana translations. But even the not-so-great translations carry the gravitas of Herbert’s poetry—enough, at all events, to make the reader in English understand why Herbert is so firmly placed in the pantheon of the great poets of the twentieth century, and why his is the kind of poetry that makes for the strongest argument for literature: that without it we would not be able to know the essential truths about living in a world that constantly militates against us seeing, against us feeling, against understanding.

Bilal Tanweer is a writer and translator. He was recently named an Honorary Fellow of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. He teaches at LUMS.

Originally published on December 2, 2012 in Dawn, Books & Authors

Mr. Cogito and the Imagination

1

Mr. Cogito never trusted

tricks of the imagination

the piano at the top of the Alps

played false concerts for him

he didn't appreciate labyrinths

the Sphinx filled him with loathing

he lived in a house with no basement

without mirrors or dialectics

jungles of tangled images

were not his home

he would rarely soar

on the wings of a metaphor

and then he fell like Icarus

into the embrace of the Great Mother

he adored tautologies

explanations

idem per idem

that a bird is a bird

slavery means slavery

a knife is a knife

death remains death

he loved

the flat horizon

a straight line

the gravity of the earth

2

Mr. Cogito will be numbered

among the species minores

he will accept indifferently the verdict

of future scholars of the letter

he used the imagination

for entirely different purposes

he wanted to make it

an instrument of compassion

he wanted to understand to the very end

—Pascal's night

—the nature of a diamond

—the melancholy of the prophets

—Achilles' wrath

—the madness of those who kill

—the dreams of Mary Stuart

—Neanderthal fear

—the despair of the last Aztecs

—Nietzsche's long death throes

—the joy of the painter of Lascaux

—the rise and fall of an oak

—the rise and fall of Rome

and so to bring the dead back to life

to preserve the covenant

Mr. Cogito's imagination

has the motion of a pendulum

it crosses with precision

from suffering to suffering

there is no place in it

for the artificial fires of poetry

he would like to remain

faithful to uncertain clarity

Translated from the Polish by John and Bogdana Carpenter

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Portrait Artist: the poetry of Harris Khalique in retrospect by Bilal Tanweer

Harris Khalique’s new collection of poems, Melay Mein, is marked by a certain weariness. These poems lack the defiant verve of his earlier poems. The poet who wrote about boldly coveting other people’s wives, about kissing a new friend at Jehangir Kothari parade on 14th of August, who celebrated sex and drunkenness and adultery, whose pitch and tone was revolutionary, who resolved life’s gravest dilemmas in a delightfully off-handed manner (kaun jaanay kia hai wafa/ kis ne dhoonde se paya khuda/ in jhamelo’n mein parne se kia/ aa’o jeenay ki baatein karein) and wrangled with the world about love being greater than the individual, greater than society, of love being its own time and space (Musheer Uncle, zamana ishq se barh kar nahin hai/…/ ishq to khud ik zamana hai/ yeh poora ‘ahad hai)—that poet, that voice is gone now.

This is Harris Khalique’s eighth book, and the occasion has led to a republication of new editions of his previous new and selected works: Ishq ki taqveem mein (Urdu) and Between You and Your Love (English; revised and expanded edition). Quite fittingly, it is a moment for deeper examination and evaluation of his work to allow it the place it deserves in the corpus of Pakistani literature. I hope this essay is a beginning of that conversation.

Compared to his earlier work, the voice in these newer poems appears worn out, more aware of life’s fragilities and body’s weaknesses, and more cynical, far more cynical about what can be achieved in a lifetime. This is a voice that is seeking refuge; it is in conversation with Husain, pleading in Hazrat Mueenuddin Chishty’s darbar, presenting verses to Shah Habib. It’s begging for favors and mercies, seeking solace. The tone of defiance, wherever it may be found, is one of martyrdom.

Clearly, things have changed.

The weariness in Harris Khalique’s new poems stem from the dissipated promise of life—a recurring theme in these poems—and the defeated ideals one has built a life on. The two couplets from the opening poem, khwab-e khush-numa, set the mood:

shayad woh khwab-e khush numa

hum ne kabhi dekha na tha

khud pe kia taari use

woh khwab jo apna na tha

However, the fatigue also seems to have extended into his language, which becomes by turn hackneyed, by turn clichéd, and—even more shockingly—vague and indulgent. I am pointing to the earlier poems in the collection, like Gha’o and Safar. The first one is worth reproducing at length:

mere gha’o bohat gehray hain

unn ka bharna sehal nahin

aik ik gha’o kee gehra’ee mein

basee hu’ee hain

khauf aur dehshat ki duniya’ein

aur inn duniya’o’n mein naach rahee hai’n

lambay kaalay choghay pehnay

pichal peri ka’ee bala’ein

saari bala’ein baari baari

andar andar

mera kaleja noch rahee hain

kafee deyr ke baad balaa jab thak jaati hai

phir se kaleja bhar jaata hai…

This poem is so spectacularly indulgent, so extravagant in its vagueness and so dull in its language that the kindest thing to say about it would that this is perhaps a poem’s way of doing an Indian soap opera. It lacks both the rigors of imagination and language that one would expect from a poet of Harris Khalique’s caliber and experience.

Other poems in this opening section of Melay Mein fare no better. Consider the ending of the title poem, Melay Mein—a poem written from the perspective of a mother ‘jiss ka bacha/ jahan-e baazi giraa’n ke melay mein/ kho gaya hai’:

woh mera masoom dil ka tukra

woh mera gul-goothna sa bacha

mein uss ke sadqay mein uss pe vaari

mein apna sukh, apna chen haari

khuda hee ab mujh pe rehm kha’ye

khuda hee hai jo hamein milaa’ye

While the poem aspires to universality with ‘jahan-e baazi giraa’n’, it fails to exert itself either imaginatively or emotionally to live up to that aspiration. The world of this poem remains vague, and no image, no line comes alive on the page (except maybe for a phrase: ‘woh be-niyazi ke khauf aaye’. Maybe).

In the covenant between a reader and a writer, there is no greater transgression than for a writer to do less than he is capable of and to not make his writing as good as he can. The fact that most of these poems were not shot to death by either the editor(s) or the poet himself is greatly dismaying. And look, the matter is even graver. We believe in poets because they look at the world harder, with more care and attention, with greater sensitivity and insight than the rest of us. I recall a moment in Jack Gilbert’s poem, ‘I Imagine the Gods’, where the gods offer to grant the poet everything: wisdom, fame, three wishes. The poet rebuffs it all:

…Let me fall

in love one last time, I beg them.

Teach me mortality, frighten me

into the present. Help me to find

the heft of these days. That the nights

will be full enough and my heart feral.

In the covenant, the role of readers is also clearly stated: to make good books possible and to make bad books impossible. Good readers must work as hard as writers. We must demand more life, more heart, more imagination from our writers. They must tell us what it is to be alive. Frighten us into the present. Help us find and lift the heft of these days.

What I am saying is this: the dream of literature is to be richer, fuller—even greater than life. Literature should never betray that promise. We can all live with a world that betrays us, but not literature.

But let me not get carried away in my frustrations with these early poems of Melay Mein. There are more good poems in this book than bad, and to be sure, this is a moment of celebration.

For those not familiar with his work, Harris Khalique has written poetry in three languages (Urdu, Punjabi and English) and has a distinct voice in each one of them. His verse in Punjabi is most lyrical of the three, while in English it is at its sparest and most direct. His English verse shows a range of influences—from Borges, Nazim Hikmet, Czeslaw Milosz, Amichai, Qabbani (whose poem he has translated: ijazat mil sake gee kia?) to Taufiq Rafat, and over the years he has written some truly remarkable poems in English. Consider, for instance, his poems on Karachi. Here’s one (perhaps the finest):

I was raised in Karachi

When young I always asked my mother:

"Why can't we give names to numbers and numbers to names?"

It took her twenty-five years to come up with a reply.

"Son, we name the streets and count the people."

Three Unknown Men Killed on M.A. Jinnah Road

read the morning's newspaper.

Examining his oeuvre in languages, one realizes that Harris Khalique’s best poems are made not of ideas but people: Kaana Bati Koo, Ghulam Azam Musalli, Nazeer Alam Gavayya, Sabeen Ehsan Akhtar—Defense Phase II, Ali Mohsin MBA—Khalid bin Waleed Road, Razia Sultana—Korangi K-Area, Sa’adat Khan Baloch Rakshay Waala—sakana Purana Golimaar, Muzammil Ghari-saaz, Uncle Jacques and others.

Character portraits are Harris Khalique’s forte. He can pull them out of thin air and make people stand in front of you in a manner that can safely be described as shockingly vivid and exhilarating. He buses you through his characters’ work days and their domestic squabbles, and details their drawing room gossips, the thickness of their lips and their sexual interests. His portraits have both the lightness of touch and unsentimental compassion that makes for great writing, and reading them you wonder if any other contemporary writer from Pakistan—bar none and no genre—has been able to create such characters with so much clarity, conviction and above all, with such deep and abiding humanity. Those two boys who died yesterday in police firing near Sindhi Hotel, Lalu Khet, they are in these pages telling each other dirty jokes, cussing, eyeballing girls on the street and saying shit to passersby. Ghulam Azam Musalli, who serves Malik sahib, cleans and refills his hookah and beats up the opposition workers come election time, is dealing with the unbearable rash in his armpits and pubis, and trying to bear the loss of his son who died at birth. Nazir Alam Gavayya, who has been practicing his craft of singing for a lifetime, now wakes up in the middle of the night, and we get to glimpse his nightmares. They are the contours of the world we live in.

The last time you saw such terrific portraits were in the work of Majeed Amjad, that master. Think of his brilliant portrait of Manto, which opens:

mei’n ne uss ko dekha hai

ujli ujli sarko’n par aik gard bhari heraani mei’n

pheltee pheltee bheer ke andhay aundhay

katoro’n ki tughiyaani mei’n

jab woh khaali botal phei’nk ke kehta hai

“duniya! tera husn yahi bad-soorati hai”…

But Harris Khalique’s portraits are even more remarkable and stand on their own because a. they are no hagiographies; and b. his characters don’t simply have names and faces, they also have an address. Harris Khalique’s poems have an extraordinary tendency to move away from the abstract. His cast of folk have no time for existential dilemmas because they are all busy untangling themselves from the ensnaring world they inhabit. They are busy earning their share of sadnesses from the world, while he exquisitely lays bare the interstices of power on the spectrums of gender, class and space where they fall. In that sense, Harris Khalique is a good Marxist (as opposed to, you know, a Marxist) because he understands Faiz and Hikmet: meri jaan tujh ko batla’oon bauhat naazuk yeh nukta hai/ badal jaata hai insan jab makaan uss ka badalta hai.

While Harris Khalique has some gems in ghazals, nazms that also deserve a careful and detailed reading, I believe it is in his portraits where he delivers on one of the essential promises of literature: to illuminate our world and render it legible. It is this work that marks him as one of our truly original voices, a true portrait artist of our times.

Bilal Tanweer is a writer and translator. He teaches at LUMS.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors - September 23, 2012

0 notes

Text

Notes from the Countryside by Bilal Tanweer

Qa’im Din by Ali Akbar Natiq

Publisher: OUP Karachi

114 pages

Year of publication: 2011

Price: Rs.325.00

You’d think the job of a book description involves point-blank lying to fool the readers into buying the book. You know nothing obviously, because here’s a book where the book description is trying to pass a quasi-academic lecture off as a sales pitch. The description on the jacket of Ali Akbar Natiq's collection of stories, Qa’im Din, introduces him as follows: Urdu afsane mein haqiqat nigari ne dobara apni hesiyat, balke apni afadiyat manwa li hai. Qayam-e Pakistan ke das barso'n ke andar alamati afsana haavi ho chuka tha… [Realism has reclaimed its place in Urdu fiction; in fact, it has convinced it of its value. Within ten years of Pakistan's independence, the alamati afsana had dominated the Urdu literary scene...]

It goes on for a bit so I’ll paraphrase the rest: For too long, Urdu fiction has mucked around in abstract stories (alamati kahani is the term of choice. It means many things, but mostly it refers to deviants from conventional realist modes of writing). Urdu fiction must now come back to earth and start telling us stories about REAL people, REAL places and REAL situations. Ali Akbar Natiq has done it. He’s awesome. Buy the book. (Okay, it doesn’t say buy the book.)

One thing is clear: this book description isn’t looking for potential buyers. It is only speaking to Urdu writers and critics who love the alamati kahani. At all events, regardless of what one thinks of the larger landscape of Urdu fiction and the narrow definition of 'realism' so deeply cherished by the author of this description, it is a pretty accurate summation of what Ali Akbar Natiq delivers in his debut collection of short stories, which has been received enthusiastically by the Urdu literary community. Leading critics and writers including Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, Ajmal Kamal and Mohammed Hanif have hailed Natiq as a fresh new voice in Urdu literature. (Mohammed Hanif has also translated a story from this collection, Me’mar ke haath into English for Granta; it is a very fine translation and available on the Granta website as Mason's Hands.) It wouldn’t be wrong to say that this is the giddiest the Urdu literary community has felt about a collection of stories in recent years. That in itself is not to be taken lightly.

The major distinction of Natiq's stories, duly noted by all the critics who have commented on his work, is their ability to capture the scenes and rhythms of the Punjabi countryside. All these stories are unfailingly good in their ability to portray the lives of characters in a Punjabi rural setting. Natiq exhibits a particular flair for character with an enviable range: his stories feature characters that include Chaudhrys, gravediggers, pirs, dogfighters, thieves, scandal mongers and elopers and more and more. Yes, when it comes to profusion of characters, these stories keep giving.

It is no surprise then that the standouts of the collection are the five longer stories. These are the stories that allow Natiq’s numerous characters to find their space and express themselves. It is also in these stories where Natiq is able to chart his characters’ development over a longer course of time with fine results: the scenes in these stories are solid, the pacing is steady, and Natiq’s facility with language admirable throughout. However, most of this collection comprises relatively shorter pieces (eight pages or less). These stories lack the finish and the imaginative flourish of the longer ones and do little more than providing reportage-like snippets of village life. That works too, but the impact is necessarily very limited.

The best story in this collection by far is Mominwala ka safar. It is a comic story set in a Model Village which is battling the menace of herons that for some unknown reason have settled in the thickets of trees in the village. In order to get rid of the pest, the village folk reach the difficult consensus of cutting down the branches of the trees. But when this plan is executed, it leads to the carnage of hundreds of heron eggs and babies that fall and get injured and killed. The spectacle provides Naziran—the village tattler and scandalmonger who commands great fear and respect for her tongue—an opportunity to take the Chairman of the village council to the cleaners. The story is an account of Naziran attempting to abuse the Chairman and the latter tactfully trying to ward off the punishment that she is bent on delivering. The story, like other stories in the collection, has a surprising end but it is in the tradition of best short fiction—it not only surprises but also gratifies the reader.

As for the other longer stories here, while Natiq does a fine job dramatising character and setting, his stories end predictably. Almost all the stories have a similar end—accidents. The characters in his stories are rarely devastated by their own choices; instead, they are undone by things like bad luck and deadly floods. The result is that promising stories are often lost to what comes across as a hasty end, and at its worst, a didactic urge on the part of the author. A good example of this is the story, Me'mar ke haath—one of the strongest in the collection.

Me’mar ke haath features the mason Asghar who specialises in making minarets. Although he has an established practice in his local village, he departs for Saudi Arabia to seek greater fortune and glory against his father's wishes. The story follows him through his travails at the Jeddah airport and city to Mecca and observes him wandering the alleys in Medina, where he is deceived, swindled, and ultimately, arrested for thievery. The story ends in a scene where he is being executed. The story contains beautiful, surreal sequences but the end is so stark, so sudden and so complete that it spectacularly reduces this intriguing story into a fable. The sense of life ends with the last line of the story.

It is pretty much the same case with the other great hero of this collection, Qa'im Din, a thief who has mastered the treacherous forest terrain on the Pakistan-India border close to his village. Every few months, he carries out heists where he slips through the forest (repelling cobras with a holy charm and cutting down the wild boars) to reach the villages that lie on the Indian side of the border where he makes off with several buffaloes at a time. Strong, smart and sensitive, Qa'im Din has all the qualities of a powerful mythic hero. But his fate is also sealed swiftly and suddenly. He is bludgeoned and executed twice over, and on both instances, it is little more than a conspiracy of the heavens.