Text

Discuss the relationship between place, identity and displacement through the case of mainlander forced migrants of 1949 in Taiwan.

Author/ Chi Chu

‘The embodiment of the homelessness refers to the circumstances of the refugees away from 'home'”, Warner (1994, p.48) ever states. This was also the experience for 'mainlander forced migrants' in 1949. 1937 to 1960 was the most chaotic period in modern Chinese history. After the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Civil War and the Korean War, a large number of people were forced to migrate between China and Taiwan. After the Chinese Civil War (1945-1949) between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party, the government of the Republic of China (ROC) retreated to Taiwan in 1949. Since then, mainland China has been governed by the People's Republic of China (PRC). At the time, about 2 million 'mainlander forced migrants'[1] migrated to Taiwan and became one of the 'rootless groups' in history. Using this case, this essay discusses the relationship between place, identity and displacement through analysing post-war literature. First, the essay will consider how migrants shape nostalgia and the 'sense of places' through 'a taste of home' or 'ritual' to establish their identity and sense of belonging to hometown. Second, it aims to discuss how mainlander forced migrants have confronted the double ambivalence and transformation of identity while/after 'returning home'. Finally, this essay argues that the relationship between place, identity and displacement is a dynamic process. For mainlander forced migrants who moved to Taiwan after 1949, their identity is mainly influenced by the political situation between China and Taiwan and memory shaped by forced migrant communities.

The sustenance of displacement and nostalgia have been the collective experiences of mainlander migrants who left their hometown (mainland China) in 1949 but could never truly return to their hometown physically and psychologically. One of the reasons is the dilemma of the political situation between China and Taiwan. Because the new regime, the PRC, has governed mainland China since 1949, these displaced people from the mainland have experienced a kind of political displacement. Meanwhile, not only was the international refugee system still in the process of being established at that time, but the protection or settlement policies for these forced migrants was also incomplete (Nedostup, 2010). So far, the displacement from 1945 to 1949 caused by the Chinese Civil War is still a major talking point. Hence, the mainlander forced migrants, who have been difficult to catalogue in the relief system or following refugee conventions, have been put on hold by the international community and are framed up in the political conflicts between China and Taiwan (Ibid). Looking at history, Lary (2010) shows that, for many Chinese people, the wars meant endless separation, which was a sudden incidents without any signs, and it just happened naturally. In a documentary about the life of mainlander forced migrants in Taiwan, Hebei Taipei (2016), the protagonist, Li, mentions that all the roads he had travelled were not ones he would have chosen himself, but were forced on him by the external situation: 'it was fate that chose me.' This is indicative of the experience of mainlander forced migrants. For them, Taiwan is not their home: their real hometown is in mainland China (Taiwan People News, 2015). As Turton (1996) states, “one assumption of 'displacement' indicates ideally people 'belong' to a certain place and gain the identity from their association with a particular place fundamentally or naturally” (Cited in Kiberab, 1999, p.405). However, returning to the hometown has become a utopia for mainlander forced migrants. In turn, nostalgia and the cohesion of the forced migrant community can be observed in post-war literature, through which migrants attempted to reconstruct the memories of their hometown during their displacement. Yu (2011[1974]), part of the first generation of mainlander forced migrants, describes the attachment to hometown in his poem, Nostalgia:

When I was a child,

Nostalgia was a tiny postage stamp,

I, on this side,

My mother, on the other.

When I was older,

Nostalgia became a ship ticket,

I, on this side,

My bride, on the other.

Later,

Nostalgia was a squat tomb,

I, outside.

My mother, inside.

And now,

Nostalgia is a coastline, a shallow strait.

I, on this side,

The mainland, on the other.

It can be observed from Yu's text that displacement is a lack of existence, perhaps more fundamental than the lack of shelter (Cresswell, 2004). It means that mainland migrants were forced to leave their hometowns and lost the sustenance of their hometowns in the process. Also, through Yu’s expressions, 'here' and 'there', the hometown is depicted as far away. Moreover, through expressions of nostalgia, mainland China is undoubtedly a place of inner connection and a sense of belonging (Augé, 2017, p. 60). Yu's poem also responds to Kibreab's (1999) statement that “the propensity of many societies, including formerly 'cohesive' ones, to define themselves based on their ethnic, national or spatial origin, or religion”. This indicates that in Yu's texts it can be seen that the description of his ethnic origin through the relationship between mother/ mainland China (on the other side) and him/ Taiwan (on this side). Also, Relph (1976) notes ‘ the roots are significant to provide people a point of prospect and the attachment of a particular place in terms of spiritual and psychological sides. For human beings, it is an essential need to be attached and have deep ties to places. Hence, in the nostalgia of mainlander forced migrants, spatial origin and the roots represent place attachment psychologically. Besides, ‘place attachment is often defined as 'an affective bond or link between people and specific places'’ (Hidalgo & Hernández 2001; Cited in Windsong, 2010, p. 206). For instance, Tang (1979, p. 2), a food writer and first generation member of the mainland diaspora, describes how 'the taste of food provokes my nostalgia of hometown. It would bewonderful if all mainlander forced migrants could return to the mainland and try a taste of hometown.' This implies that a taste of home represents the place-based, physical attachment of hometown. Additionally, over time, for mainlander forced migrants who have not been able to return to their hometowns, it has been necessary to restore and re-establish a set of cultural customs belonging to their hometown to maintain their roots (where they are from) and release the nostalgia (Sun, 2010, p. 48). For them, nostalgia and the spiritual substance of hometown are pin on a particular object or practice, such as a taste of home and ritual. These objects/practices represent the reappearance of 'place', which can be imagined and even reconstruct the memory of hometown. As a consequence, these objects/practices encapsulate a sense of place and Les Lieux de Memoire (Nora). As Tuan (1975;1990) states, the place becomes a symbol of spirit to express emotions, not just to indicate location or function. The thought of home transcends the boundaries of residence and includes places that are often described as 'sense of place' with a sense of belonging (May, 2000, p. 748). As mentioned above, in a displacement context, the place provides spiritual and memorial sustenance and is not just a physical place but can also be a sense of place presented in any object.

The memories and identities of hometown formed by displaced mainlanders take shape through practices such as food literature or rituals in the alien land. In the process, a desire to return to their hometown is created. For instance, as Chung (1959) mentions in My Native Land, 'the blood of the native villagers must be flown to the original hometown to be stopped.' This means that the nostalgia of mainlander forced migrants will stop only when they make their return. Due to the political situation between China and Taiwan, mainlander forced migrants were not allowed to visit relatives in China and 'return to their hometowns' until 1987. Nevertheless, the experience of returning to their hometown has also become a critical point to deny the imagination of mainland China shaped in these four decades by mainlander forced migrants. During this time, the mainlander forced migrants became truly psychologically 'rootless' and lost their identity. Identity has the function of identification and connection for individuals. It distinguishes the difference between insider and outsider, and connection meets the sense of belonging between individuals and communities. In the case of mainlander forced migrants, when they returned to their hometowns they discovered that profound changes had occurred in the past few decades. This made their mental connections to the landscape disappear (Lin, 2010, p. 304). As Chu (1992) mentions in In Remembrance of My Buddies from the Military Compound, ‘the moment when I was able to return to my hometown, I found that for my relatives who remained I was a Taiwan compatriot and a Taiwanese; However, when going back to the Island (Taiwan), where I have lived for over four decades, people refer to me as a member of the mainlander forced migrants from the other province of mainland China… Thus, I have a deep feeling that I am like the displaced bat, which cannot be classified into bird or vertebrate’. Chu (2002[1997], p. 213) also states the mistake about her ancestral history in The Ancient Capital. For Chu, people blame forced migrants for retreating to Taiwan in 1949 and abandoning ancestral tombs and the reunion with family. Another example is the documentary, How High is the Mountain, which reveals the relationships within individual encounters of mainlander forced migrants and history after 1949. In one scene, a son asks, 'How did you feel when you went back to your hometown yesterday?'. His father replies, 'I do not know anyone ... all have changed'. 'Will you want to go back again?', the son asks. Father shakes his head and says, 'it is not like my hometown at all. My original house is gone.' In the cases mentioned above, the disconnection from hometown is a response to the difference of sense of belonging, as well as the disparity between ‘self’ (forced migrant) and 'others' (hometown). Furthermore, mainland migrants sink into a dilemma because they belong to neither their original hometown nor Taiwan.

Accordingly, whether the ‘identity’ would truly transform after a while when the original hometown is no longer how it appears in memory. For mainlander forced migrants, the identity of 'outsider' signifies that nowhere can be attached and status of displacement—not only outside Taiwan but also outside the hometown in mainland China (Mei, 2006, p. 12). Even though displacement is still constant, psychologically, these mainlander forced migrants have recognised they have lived for most of their lives in Taiwan and have recognised Taiwan. However, the identity of mainlander forced migrants has been continuously split by the political situation between China and Taiwan. The identity issue has continued to ferment (Yang, 2010, p. 64). The first reason for the identity issue is that the governments of ROC and PRC have emphasised the 'homogeneity' of identity in the post-war era in order to establish the coherence of opposite political ideology between China and Taiwan, respectively. Consequently, this long-term opposing position has created a difference in consciousness/ideology/memory between mainlander forced migrants and their families/hometowns. Secondly, because the Taiwanese political environment has changed drastically since 1949, mainlander forced migrants have been marginalised in Taiwanese society. The atmosphere of society had changed from Chinese consciousness to local Taiwanese consciousness (Lin, 2010, p. 313; Ko, 2010, p. 81). The reason was a series of political conflicts that took place in Taiwan after 1949, such as the 228 Incident, which accelerated the differentiation between mainlander forced migrants and local Taiwanese . Therefore, for mainlander forced migrants, they are neither Taiwanese nor Chinese because of the difficulties in the processes of assimilation and acculturation. ‘They are just a wandering soul that has no place to go/ belongs.’ (Lin 2019). The situation faced by mainlander forced migrants corresponds to the concept of 'double ambivalence' proposed by Weisberger (1992) in Marginality and Its Directions. This idea indicates the anxiety of migrants facing a marginal situation in an alien land. This anxiety stems from the difficulty striking a balance between the culture of the alien land/new nation-state and the hometown/native nation-state. Neither can migrants rule out the influences created by their native culture. Consequently, migrants are in a marginal position, not in-between, but unable to adapt to each side, resulting in the double-ambivalence. They can only return to their native hometown geographically but cannot truly go home psychologically. This indicates that mainlander forced migrants have confronted the dilemma in the sense of belonging/identification and might they retreat to the margins of society.

As mentioned above, mainlander forced migrants have faced the split between 'hometown' and 'nation-state' which has changed their own identities. According to Crowley (2003), who discusses the concept of narrative identity proposed by Paul Ricoeur, there are two types of 'identity': idem and ipse. Ipse identity corresponds to the relationship in the space-time context produced through the accumulation of cultural construction, narrative body and time. Often it must be reproduced through the subject's narrative. Not only can it only be formed in the process of continuous construction, but also often generates various deformations under the cultural norms. For example, great differences in the identity consciousness of hometown can be observed between different generations. Due to social oppression, although new generations recognize Taiwan, they continue the consciousness of hometown and the sense of national identity from older generations (Ko, 2012, p. 41&146), resulting in a double identity of nation-states (Shen 2010: 128). There is such a difference of identity because, for the second generation, life in Taiwan is their first memory instead of in mainland China. Therefore, in response to Ricoeur's statement, the identity of mainlander forced migrants in different generations is a continuous construction between self and history/environment. Therefore, identity is an invisible and dynamic process/concept.

Overall, according to the case of mainlander forced migrants living in Taiwan after 1949, it can be seen that the relationship between place, identity and displacement is a dynamic process, which is not only based on the changes of time and space but also reflected in the political context, the inner cohesion of displacement communities, the meanings of identity for different generations and more. Furthermore, for mainlander forced migrants in 1949, even 'return' cannot eliminate their psychological or physical displacement. Because of long-term displacement, the memories caused by nostalgia, rather than a visible place, become an 'imaginary place', the spiritual attachment onto which forced migrants hold. Consequently, the double ambivalence of place and identity presents the displacement situation in the context of forced migrants.

Reference

Augé, M. (2017[1992]). NON-LIEUX: intruduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité [In Chinese] trans. By S. Sun. Taipei: Garden City Publishers.

Chu, T.-H. (1992). In Remembrance of My Buddies from the Military Compound [In Chinese]. Taipei: Rye Field Publishing Co.

Chu, T.-H. (2002[1997]). The Ancient Capital [In Chinese]. Taipei: INK.

Chung, L.-H. (1959). My Native Land [In Chinese]. Available at: http://cls.lib.ntu.edu.tw/hakka/author/zhong_li_he/he_composition/he_onlin/short_stoy/short_16.htm (Accessed 10 May 2020).

Cresswell, T. (2004). Place: A Short Introduction. US: Wiley-Blackwell.

Crowley, P. (2003). Paul Ricoeur: the Concept of Narrative Identity, the Trace of Autobiography. Paragraph, 26(3), p. 1-12.

Kiberab, G. (1999). Revisiting the Debate on People, Place, Identity and Displacement. Journal of Refugee Studies, 12(4), pp. 384-410.

Ko, P.-W. (2010). The Research of "Home-Country Writing " of Taiwanese Proses After 1980s [In Chinese]. PhD Dissertation, National Cheng Kung University.

Lary, D. (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937-1945 (New Approaches to Asian History). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, N. (2015). Hebei Taipei [Documentary in Chinese]. Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4842868/ (Accessed 10 May 2020).

Lin, Klaw (2019). No Place to Go and Belongs. [In Chinese]. Available at: https://living.taronews.tw/2019/11/22/537312/ (Accessed 10 May 2020).

Lin, P. (2010). Being Strangers at Home: Mainlander Taiwanese in China. In M.-K., Chang (ed.) Nation and Identity: Perspectives of Some “Waishengren”[In Chinese]. Taipei: Socio Publishing Co. Ltd, pp. 301-329.

May, J. (2000). Of Nomads and Vagrants: Single Homelessness and Narratices of Home as Place. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 18(6), p. 737-759.

Mei, C.-L.(2006). The Vicissitude in Mainlander Association (eds.) The Memory in Drifted period: Undeliverable family letters. Taipei: INK.

Nedostup, R. (2010). Defining Displacement: A Few Problems in Analyzing Wartime Refugees in China and Taiwan, 1937-1960 [Lecture]. Available at: http://ccs.ncl.edu.tw/files/1217%E5%BC%B5%E5%80%A9%E9%9B%AF%E6%95%99%E6%8E%88%E6%91%98%E8%A6%81.pdf(Accessed 10 May 2020).

Nora, P. (1989). Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire, trans. by M. Roudebush. Representations, 26, p. 7-24.

Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. London: Pion Limited.

Shen, S.-C. (2010). Fatherland and Homeland. In M.-K., Chang (ed.) Nation and Identity: Perspectives of Some “Waishengren”, 111-146) [In Chinese]. Taipei: Socio Publishing Co. Ltd, pp. 111-146.

Sun, H.-Y. (2010). National Identity of Waishenren, the Second Generation in Taiwan. In M.-K., Chang (ed.) Nation and Identity: Perspectives of Some “Waishengren” [In Chinese]. Taipei: Socio Publishing Co. Ltd, pp. 31-74.

Taiwan People News (2015). Discussion of political identity [Online Essay in Chinese]. Available at: https://www.peoplenews.tw/news/ebd2a5b4-99a2-43d2-9ff1-04d6fd31e4e2 (Accessed 10 May 2020).

Tang, L.-S.(1979). Get Away from Home. Taipei: China Times Publishing Co.

Tuan Yi-Fu (1990). Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values. NY: Columbia University Press.

Tuan, Yi-Fu (1975). Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes and values. Human Ecology. 3(2), p. 131-133.

Warner, D. (1994). Voluntary Repatriation and the Meaning of Return to Home: A Critique of Liberal Mathematics.Journal of Refugee Studies,7(2/3), p. 160-174.

Weisberger, A. (1992). Marginality and Its Directions. Sociological Forum, 7(3), p. 425-446.

Windsong, E. A. (2010). There is no place like home: Complexities in exploring home and place attachment. The Social Science Journal, 47(1), p. 205-214.

Yang, M.(2010). The Aesthetics of Nostalgia: The literature of Mainlander Authors of 1949. [In Chinese]. Taipei: Showwe Information Co., Ltd.

Yeh, J. & Tanf, S.-C. (2002). How High is the Mountain [Documentary in Chinese]. Taipei: Taiwan Public Television.

Yu, K.-C. (2011[1974]). Nostalgia[In Chinese]. Wuhan: ChangJiang Literature.

[1] In her lecture, Nedostup (2010) discusses how government officials found it difficult to define the veterans and civilians who migrated to Taiwan after 1945, and especially in 1949. Political and cultural uncertainties are reflected in the terms used in documents and in secondary historical materials, including political categories (compatriots), geographic cultures (mainlander diasporas/forced migrants), and social categories (refugees).

0 notes

Text

Discuss the role of Palestinian cuisine in identity and collective memory formation for Palestinians

Author/ Chi Chu

Food constitutes ‘a highly condensed social fact’ and ‘a marvellously plastic kind of collective representation’ (Appadurai, 1981, p. 494). This research project begins to discuss the relationship between food, collective memory and identity for Palestinian diasporas overseas through the concept of daily food and commensality Food has come to represent the juxtaposition of rights in daily life: strategic (the system of the nation-state, such as large-scale suppression) and tactical (people’s guerrilla resistance) (de Certeau, 1984). Historical Palestine has experienced many ethnic settlements and nations and is deeply affected by political and social divisions, conflict and violence. The food culture has become not only the core of family, the nation-state, and identity but also the medium of political ideology. It is also the thrust of living together and erasing borders. Therefore, this ethnography will present perspectives on the Palestinian cuisine of Palestinian diasporas with regards to individual identity and collective memories through the use of interviews, participant observation, and detailed discussion.

In history, Palestinian food has been merged with the food culture of other regions and reinterpreted de-Palestinianization due to migration and conflicts. Belasco (2008) states that the same story of ‘delocalization’ is everywhere. It means that one ethnic group would invade, colonize or dominate another ethnic group/nation-state. Hobsbawm (1993) also states that the distinctiveness of creation is that the correlation between such traditions and history is ‘artificial’. Briefly, the created tradition is a response to a new situation, it appears in a form related to the past, or it builds its past in a repeating manner in a similar nature of the obligation. Hence, what is Palestinian food culture after decades of separation? Halbwachs (1992) states that external values affect individuals in several ways. Also, the history of ethnic groups shapes their identity under the social structure and memories become the path of history. As mentioned above, when encountering the decades of separation from the land and other members of the ethnic group for the Palestinian diaspora, the transformation of individual identity or collective memory tends to be significant. Therefore, the following will present interviews on how Palestinian food provokes the collective memory of Palestine (land).

Part I: Participant observation

I joined a Palestinian supper club on Friday, Nov. 8 in 2019, at Café Palestina in north London which endorses ‘commensality’. In the beginning, I thought every participant would share food on the same table. However, participants used different tables at the supper club, whose members are western people, not Palestinians. They had their dishes set, and they included falafel, hummus and a few salads, and there was no conversation between each table. The scene was similar to dinner at a restaurant. According to one member of the Palestinian diaspora, H (2019), sharing food is the core concept of Palestinian food culture. However, it was difficult to find any characteristics of the concept of ‘commensality’ during the whole process of the Palestinian supper club. Moreover, participants left directly after finishing their meals. In the whole process, the staff of Café Palestina did not engage in the supper club or have conversations with participants.

In order to understand the core idea of the Palestinian supper club, I attempted to interview the owner and staff of Café Palestina. However, I met several challenges. In the beginning, making contact to arrange the meeting went smoothly, however as time went on, the owner started to defer the date of our meeting because there would be several events in the following weeks. Ultimately, I have not done any interviews with the owner or staff. In terms of participant observation, significantly, the supper club omits not only the sharing concept of Palestinian food culture but also the main dishes of Palestinian cuisine.

Part II: Interviews

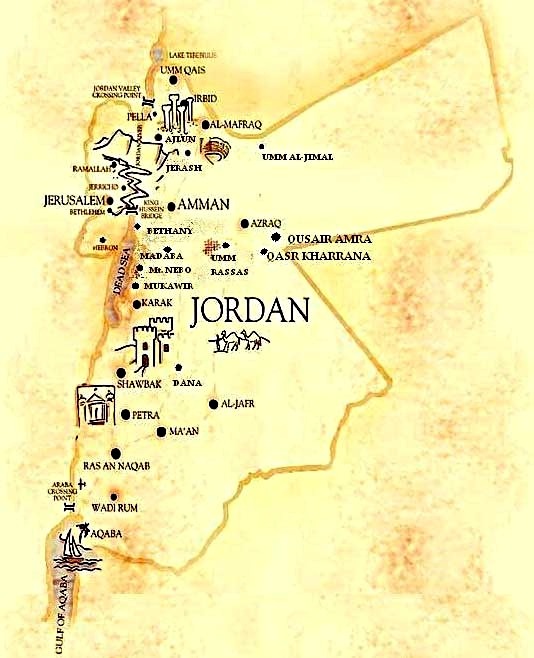

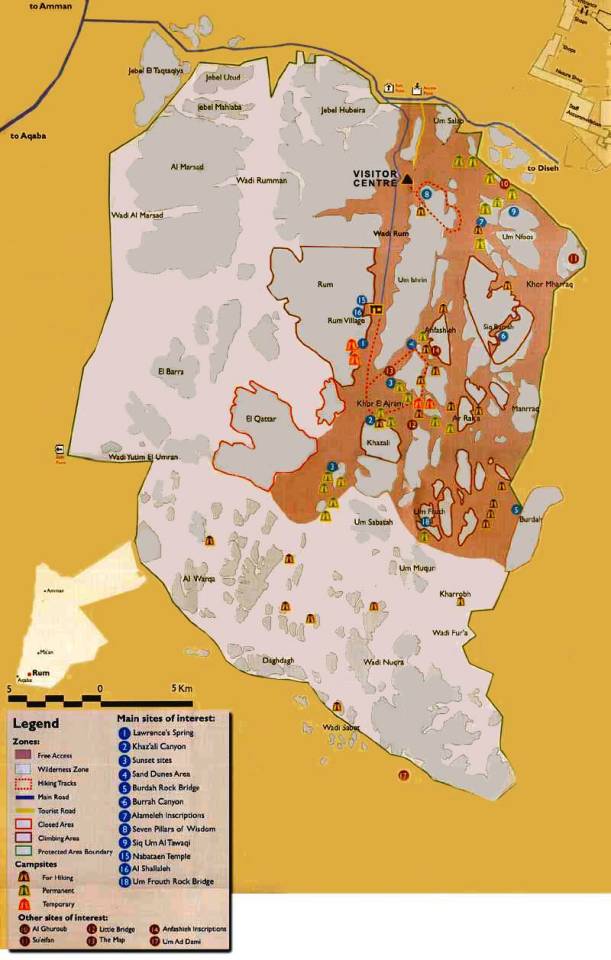

I encountered challenges not only when conducting participant observation, but also when interviewing members of the Palestinian diasporas who reside in London. The difficulties were like disconnections or asking the payments for interviews. Therefore, in the middle of the research process, I decided to change the main research targets to members of the Palestinian diaspora who live ‘overseas’ and have done three interviews with people who live in Turkey, Qatar and Jordan, respectively. Part II is divided into three sections: the memory of the land, the role of Palestinian cuisine, and the process of the blending, occupation and labelling. Each section aims to present the perspectives on Palestinian cuisine held by Palestinian diasporas.

The memory of the old city of Jerusalem

After visiting the Middle East last year, I walked down a London street and smelled the flavour of falafel at a church near King’s Cross Station. I spoke to the owner of the falafel shop, who was Palestinian. After exile since 1948, many Palestinians moved overseas, including to the UK. The familiar flavour took me back to those days of my trips in the old city of Jerusalem, which was one trade stop on the incense route from Yemen and Oman, through historical Palestine, to the Mediterranean. The old city of Jerusalem is also the principal city of historical Palestine. Arab merchants have sold myrrh, frankincense, spices and various Arab cuisines along the route. In the old city, there is evidence that vendors sell various Middle Eastern foods, such as falafel (فلافل), hmmus (حُمُّص), and kebab. Hence, Palestinian cuisine is merged with several food cultures of other regions in the land, Historical Palestine.

Over the decades, conflict affected Palestinian history and food was an essential part of life. Badkhen (2010) describes her experience in Afghanistan and those of the people she interviews on the battlefield in her book Peace Meals: Candy-Wrapped Kalashnikovs and Other War Stories. Even though the flames of battle raged everywhere, residents still invited her to have dinner at home and prepare dishes for festivals. Accordingly, food becomes a tactic to maintain the happiness of daily life. The same scenes occur in Palestine and with Palestinians. In my interview with H (2019), who is from Gaza, he said, Maqluba is a classic Palestinian dish that is not available elsewhere. We eat Maqluba to celebrate whatever the status is worst. Maqluba means pot in Arabic, and is mixed lamb, rice, garlic and various spices in a copper pot cooked in an oven. It is served with tomato salad and yoghurt. Traditionally, it is a party food. After meals, it is the dessert and coffee time, featuring Kenafa, ataif or Ka’ek bi ajwa, followed by Turkish coffee with cardamom (qahwe) or mint tea (shay wa nana). F (2019), who lives in Turkey, says that food is the core of life and the representation of our homeland for Palestinians.

The role of Palestinian food in Palestinian culture

A second generation member of the Palestine diaspora, M, now lives in Jordan. He believes the essential idea of Palestinian traditions is hospitality. Everyone offers a cup of tea or coffee when passing a store or home. Palestinians are known for their delicious food, drinks, sweets, olive oil, herbs, Waraq Inab (made from ma’loubeh, grape leaves, eggplant, and zucchini), lentil soup, and desserts like Kanafeh. For over 1200 years local olives are still producing the best olive oil in the world (M, 2019).

Identity includes factors such as taste, family and ethnic background, and individual memories which are the association of particular food and past events. The cultural identity of food includes widely shared values and ideas, and specific preferences and practices that set a community apart from others. Following the approach of anthropologists Peter Farb and George Armelagos (1980, p. 190-98), ‘a broader perspective is taken by this essay, one that advocates that all groups have a discernible cuisine that is reflected in a set of shared rules, customs, communication and habits. (The word ‘culture’ has a similar meaning. It extends beyond Shakespeare, performance, and art, and contains a standard set of ideas, imaginations, and values that express and influence the way people think and act.)’ (Belasco 2008, p.15). A (2019), shares thoughts about the cultural role of Palestinian food: ‘I hate to eat alone and never eat alone. Food is a medium of communication between family and friends, the dining table becomes an essential place for sharing. For example, every weekend, especially on Friday, we always make traditional foods, such as mansaf and makluba, which is called slow food by A.’ No matter what meal you have with colleagues, family or friends, people always enjoy food slowly and share conversations about housework, work, social issues whilst eating. The meeting of breakfast and the commensality of the dinner play an important role in Palestinian food culture. The meaning and feeling of food is my childhood memory with family or specific scene (H, 2019). Those processes construct Palestinian identity and memory of the land and cohere the ethnic group. Similar Palestinian food culture can still be tasted at the homes of Palestinian diasporas. Food is kind of memory, a sense of belonging, and identity (H, 2019). For them, food is always the identity of the homeland.

The process of the blending, occupation and labelling

As mentioned above, food is one way to convey status symbols, history, culture and values. It means that it is a common topic among all parties, invoking the shared history and culture of Arabs and Jews after a thousand years of integration. This is easily forgotten when politics is divisive. Even though conflicts between different ethnic groups continue, there are many chefs from all ethnic groups that, by cooking together, use food as a medium to bridge religious and political differences in history, traditions and cultures. A postcard that impressed me shows falafel with a Palestinian flag covering the Israeli flag (Figure 1). Hence, I asked H for his opinion on the ability of food identity.

Anderson (2006) states in Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism that the concept of the nation-state actively promoted in a specific homeland can make the community think themselves part of it. Hobsbawm (1992) also states that individuals are constantly reminded to be part of the state by various symbols in specific territories. During the wars and conflicts between Palestine and Israel, whatever the ethnic group is, Palestinians in exile keep sharing the traditions and cultures of Palestine. Jews in the Nazi concentration camps shared matzo to gain emotional support. Therefore, food is significant for ethnic identity, but it can also be a form of defamation.

Recall the talking with one Jewish A (2019), and we also have falafel because Jews lives in the land for thousand years. Therefore, the food is merged different cultures and traditions of ethnic groups in historical Palestine. H said that Israelis are trying to steal Palestinian culture and identity, and everything, from land, history, folklore, traditional costumes and food. H gives the example that they describe that fried falafel, Arabian salad and tahini are Israeli. Food is a representative cultural symbol and the identity of the nation-state, which defines who we are, where we come from, and what we want to be. ‘Food exposes our souls,’ says sociologist Gary Alan Fine. (Cited in Belasco 2008:1). Regardless of the people who originally lived in historical Palestine for thousands of years or the later settlers, the diets they eat in the present are similar. As a result, the boundaries of traditional culture/ rooted identity between ethnic groups seem to have been blended gradually. The effects of assimilation have also been observed on the Palestinian diaspora, due to the influence of the surrounding society. The identity of Palestine for new generations has weakened gradually and traditional Palestinian food has been replaced by other food, especially if parents have not shared the history, memory, and identity with their offspring (H, 2019).

Conclusion

Overall, as mentioned above, the problem of ethnic identity in food culture has also become more pronounced due to conflicts and the lack of resources. Food culture seems to be a silent voice, but it is a medium that can expose the history and social development. Food is often framed as authentic through its connection to specific history and ethnic/ cultural traditions. This connection not only proves that food can withstand the test of time, it is considered to be always suitable for consumption, not a temporary dietary style, but is also true to its origins and maintains its original flavour. The reference to historicism and ethnic, cultural traditions appear in this dimension of authenticity (Johnston, 2014). Through repetition and inheritance, ethnic groups continuously shape their traditions and collective memories. However, after Zionism came to Historical Palestine, the original cultures and traditions have gradually been replaced by a nation-state and another ethnic identity. The two sides of the separation wall and the wall between different nation-states caused by the territory or borders have gradually been differentiated.

Consequently, nowadays, due to the political situation, food culture is involuntarily linked to the manipulation of nationalist hegemony. Ultimately, it affects people’s values and solidarity with the ethnic group. However, according to Bakhtin, ‘Carnival is in its entirety universal and all-inclusive, and everyone needs to join intimate communication. The square is a symbol of nationality. The carnival square is for the carnival performances with symbolic meaning’ (Cited in Liu, 2005, p.269). Thinking with the idea of Bakhtin, Palestinian food seems to be a public space, and people can freely enjoy the senses, the patterns of life and beliefs constructed by specific institutions, and create everything from the carnival. Moreover, there are still too many unseen memories and micro-histories that need to be pieced together.

Fig 1

Bibliography

Anderson, A. (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. UK & USA: Verso.

Appadurai, A. (1981). Gastro-Politics in Hindu South Asia. American Ethnologist, 8(3), 494-511.

ASA Ethical Guidelines. (2011). Retrieved from : https://www.theasa.org/downloads/ASA%20ethics%20guidelines%202011.pdf.

Badkhen, A. (2010). Peace Meals: Candy-Wrapped Kalashnikovs and Other War Stories. US : Free Press.

Behar, R. (1996). The Vulnerable Observer. US: Beacon Press.

Belasco, W. (2008). Food: The Key Concepts. UK: Berg Publishers.

BibleGateway (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.biblegateway.com/.

CADFA (Camden Abu Dis Friendship Association) (2014). Retrieved from http://www.cadfa.org/.

Café Palestina (n.d.). Retrieved from https://cafepalestina.co.uk/.

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. CA: University of California Press.

Dowson, N. & Sabbah, A., ed. (2010). Stories from our Mothers. UK: CADFA.

El-Haddad, L. & Schmitt, M. (2016). The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey. US: Just World Books.

Goody, J. (1982). Cooking, Cuisine and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Halbwachs, M. (1992) On Collective Memory, trans. and ed. by L. A. Coser. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Harvey, D. (2008) . The History of Heritage. In B. Graham and P. Howard(Ed.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity (pp. 19-36). UK : Routledge.

Hobsbawm, E. (1992). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnston, J. (2014). Foodies: Democracy and Distinction in the Gourmet Foodscape (Cultural Spaces). US: Routlefge.

Kerner, S., Chou, C. & Warmind, M. (2015). Commensality: From Everyday Food to Feast. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Khan, Y. (2018). Zaitoun: Recipes and Stories from the Palestinian Kitchen. UK: Bloomsbury.

Liu, K. (2005). Bakhtin Dialogues and Cultural Theory. Taipei: Rye Field.

Monyer, H. & Gessmann, M. (2015). Das geniale Gedächtnis: Wie das Gehirn aus der Vergangenheit unsere Zukunft macht. Munich: Germany.

Okely, J. (2012). Anthropological Practice: Fieldwork and the Ethnographic Method. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Proust, Marcel (1934). Remembrance of Things Past, Vol. 1, trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff. NY: Random House.

Samudra, J. K. (2008). Memory in our body: Thick participation and the translation of kinaesthetic experience. American Ethnologist, 35(4), 665-681.

Sutton, D. (2001). Remembrance of Repasts: An Anthropology of Food and Memory. Oxford & NY: Berg.

Till, K.E. 1999. Staging the Past: Landscape Designs, Cultural Identity and Erinnerungs politik at Berlin's Neue Wache, Ecumene, 6(3), 251–283.

UNESCO (2019). Memory of the World. Retrieved from : https://en.unesco.org/programme/mow.

Young, J. (1993). The Art of Memory: Holocaust Memorials in History. UK: Prestel.

Appendix

Interviewers

H: Palestinian Diaspora lives in Qatar

F: Palestinian Diaspora lives in Turkey

M: Palestinian Diaspora (second generation) lives in Jordan

A: Palestinian lives in Ramallah

Jewish A : Jewish lives in Eilat

Interview Transcription (One of all interviews)

Name: Hosam Wahbeh

Palestinian Diaspora from Gaza, and now live in Qatar

Interview Time: 20191209 17:00 -17:30 (UK time) through internet phone call

C: Hello

H: I am Hosam Wahbeh from Gaze. I had lived, studies (BA, MA and PhD) and worked as a professor in Germany for 20 years at age 18. However, around six years ago, I got an offer of Aljazeera to organise film workshop and journalist. So I moved to Qatar.

C: After these years, do you want to go back to Gaza?

H: Yes, I would like to visit my family. The last time was 12 years ago. Now the political situation by Israeli side does not allow me to visit even though I have Germany Passport.

C: Up till now, do you think you get used to the others’ food or cultures more than the cultures and food from your hometown?

H: Yes. I think it is not very easy to forget childhood memories even though I have lived in other countries for the decades. Also, because of that, I’m lucky to have Palestinian food with some friends.

C: So do you still cook Palestinian food by yourself?

H: Yes, actually, I cook it very well.

C: Can you share some food you cook before?

H: Maqluba, Maluheya, Hummus, Felafeh, Bamiya… Typical Palestinian foods are Maqluba and Maluheya, which are my favourites.

C: Can you share your perspectives of Palestinian food?

H: For example, you can find Maluheya in Egypt or Syria. But I prefer for the Palestinian way to make it, like a soup. The reason is that the meaning and feeling of food is my childhood memory with family or a specific scene. That’s why my preference is fixed into the Palestinian frame.

C: Do you think is there any gaps between generations of Palestinian Diaspora?

H: In my perspectives, for example, I was grown up in Palestine, so I still have the memories of Palestine. Palestine is a feeling for me. However, for those younger generations, they were grown up in other countries. Even though their family share the cultures, traditions and food with them, they cannot really/fully experience what I had experienced before. Palestinian food somehow maybe just food for those younger generations.

C: Some Palestinian diaspora who were born overseas share they have memory with Palestinian food.

H: Maybe they connect identity and nationality to Palestinian food. But for me, that kind of experiences are different from someone who was grown up in Palestine, the motherland and a place.

C: So for you, food is a kind of memory, a sense of belonging, and identity.

H: Yes. It’s interaction. I can feel my country through food.

C: Do all of your family still live in Gaza?

H: The half of them live in Gaza, and another half live in Ramallah.

C: Now, it is challenging to visit Gaza from Ramallah.

H: Yes, after intifada, it has been difficult. So my family members have been hard to meet each other for 18 years.

C: Is there any differences of Palestinian food between Gaze and the West Bank?

H: The food in Gaza is more salty and spicy, like Indian food. Another example is like Masafeh. We don’t have it in Mansafeh, but you can find it in the west bank.

C: So does the Egyptian food influence the food in Gaza?

H: Yes, I think so.

C: How do people manage food every day under the lack of the materials, resources and ingredients?

H: Most of the ingredients are from Israel, especially water. Gaza has salty water. But sometimes UN sends aid to Gaza. No one uses water from the pipe of houses.

C: Do you invite others to have Palestinian food in Qatar?

H: Yes, I would like to enjoy food with them and make this gathering as a home and solidarity. Here is not many Palestinians, even though I have lived here for six years. Up till now, I haven’t met any Palestinian.

C: What kind of relationship is between Gaza and the West Bank?

H: Even though the separation caused by political status and territory, those people who experience similar situations, occupation. Hence, we still can feel Palestine.

C: Thanks for your sharing.

H: You’re welcome.

0 notes

Text

Discussion of xenomania in East Asia and racialised migrants (‘foreign bridges’) in Taiwan

Author/ Chi Chu

The phenomenon of xenomania, such as the western dream, is prevalent in Asian. The slang, ‘the foreign moon is much rounder’, is deeply rooted in East Asian (EA) societies. Accordingly, the ‘white’ not only becomes the general standard, but also causes a presentation of self-denial of EA values. Therefore, this reaction paper through perspectives from Houria Bouteldja, Ben Ratskoff, Amira Ekwakil and other scholars will discuss the influence of ‘white patriarchy’ in EA and the racialisation of ‘foreign bride’ migrants from Southeast Asia (SEA). It will feature examples from EA and Taiwan concerning xenomania in cross-cultural romance (CCR) between local women and western men, and xenophobia surrounding transnational marriages between local men and SEA female migrants.

The first discussion is about how white patriarchy increases the perceived inferiority of East Asian males. In 2013, users of the Taiwan online forum (mobile 01, 2013) discussed the results of an experiment , which presented that Taiwanese female users of the Skout dating app have more interest in Western profile pictures than Eastern Asian profile pictures. This is a good example of the faith East Asian females have in CCR. Another case of this reported by Tomorrow News came in 2014 when David Campbell (White American) shared a series of videos of them picking-up Asian females in East Asia on the internet. These incidents provoked a series of arguments and petition #StopDavidBond (Kim, 2015). These cases indeed reveal the xenomania for the West by Eastern females, and the attitudes of white patriarchy and superiority held by a white male.

There are two historical reasons for these social phenomena. First, during the period of two world wars, the world’s great powers (white powers) divided up and colonised Asia and affected the social values of Asians. For example, China, including Chinese, was labelled the ‘Sick man of Asia’ (Scott 2008:9). Such discrimination and racism, as highlighted by Brah (2001), has always been a gendered and sexualised phenomenon. Men in oppressed ethnic groups are classified as ‘feminine’, and ‘the white man imagines the indigenous man as his feminine foil — passive and docile’ (Ratskoff 2018). This direct discrimination informs a sense of superiority for western values regarding Asia. Secondly, the traditional hierarchical system[1]is rooted in national characters influenced by traditional Eastern morality and philosophy. Consequently, Asian individuals internalise the national characters and subconsciously hold an inferiority complex while experiencing the successful progress and economic development of Western society. It is evident that Western hegemony and white patriarchy still affect the pursuit of the West (developed) in contemporary EA society, even though the economy and development of China and other EA countries have gradually taken off in recent years. Moreover, the media renders the West a utopia. Like the film, Pierre et Djemila showed, ‘how detestable our families were and how desirable French society was’(cited in Bouteldja 2017). The internal inherent values of EA present the intersection between the influence of Western hegemony and white superiority, resulting in colonialism that exists in EA until now. Ultimately, it has facilitated the core values of the male in EA, leading to the EA males’ sense of inferiority and xenomania of EA females.

The second discussion will explore the influence of white patriarchy in EA through transnational marriage between Taiwanese men and SEA ‘foreign brides’. Over time, ‘inferior other’ (Hsia 2000, 2018; Cast net 2009) has been a label for SEA migrants in highly developed regions and countries of Northeast Asia. For example, Taiwanese society labels SEA women who get married to Taiwanese men as ‘foreign bride.’ This term in Chinese, 外籍新娘, means ‘external brides (Others)’, both discriminatory and racialised. The reason for transnational marriage is that, for Taiwanese women, Taiwanese men are secondary compared to Western men as the cases mentioned above. As a consequence, Taiwanese men have chosen SEA women to fill traditional female roles in the family. In addition, because Taiwan’s economic development is better than some SEA countries, many SEA women have decided to pursue a better life through marriage with Taiwanese men (APMM, 2007). These observations show that the first comparison is between ‘Western’ (other/ developed/ superior) and ‘Taiwanese’ (self/ developing/ inferior), and secondly, ‘Taiwanese’ (self/ developed/ superior) and ‘SEA’ (other/ developing/ inferior). Furthermore, Taiwanese women, who accept Western values, juxtapose Asian and Western men, indirectly contributing to the sense of inferiority of EA males and the racism and discrimination aimed at SEA foreign brides. For these reasons, derived from the phenomenon of xenomania, transnational marriages racialise SEA foreign brides as ‘inferior others’ and affects the ‘xenophobia’. Hence, the values of white patriarchy directly/ indirectly affect EA and the transnational migrants of SEA.

Overall, as mentioned above, under the multi-faceted oppression of gender, race, class, and colonisation, colonised peoples are restricted to present themselves. As Elwakii (2017) states, the diversity of cultural forms is replaced by gradual homogeneity. The tolerance of heterogeneity has become a social issue faced by Taiwan and other EA regions. However, there are some attempts to reverse this situation. ‘We can never be free while our men are oppressed but also it is imperative to our struggle that we build a strong black women’s movement’ (Bouteldja, cited in Ratskoff 2018). Much literature and many films have portrayed Asian males beat up gangsters and protect Asian female migrants to present their masculinity (Shie 2009:45). Also, SEA migrants in Taiwan have started a Taiwanese new immigrants’ movement to promote the equal rights and replace the name ‘foreign bride’ with ‘marriage migrants’ (APMM 2007). All efforts resist the influence of white patriarchy and intangible colonialization. The continuous decolonisation by Asian males and the movement executed by Taiwanese new immigrants attempt to assist indigenous EA cultures and marriage migrants in rebuilding self-discussion and in the formation of subjectivity as feminist — ‘a thought and a form of resistance’ (Bouteldja 2017). Hence, regardless of invisible colonial oppression by western values and ‘white patriarchy’ in EA or the extensive discrimination of SEA migrants, the most critical social actions of decolonisation in EA need to be carried out by East Asians themselves, to emancipate intangible colonial oppression.

Reference

APMM (2007). Attitude of the Local People to Foreign Brides: A Research Project by the Asia Pacific Mission for Migrants. <http://www.apmigrants.org/articles/researches/research-attitude-local-people-foreign-bride.pdf>.

Bouteldja, H. (2017). We, Indigenous Women. E-Flux, 84. <https://www.e-flux.com/journal/84/151312/we-indigenous-women/>.

Brah, A. (2001). Re-framing Europe: gendered racisms, ethnicities and nationalisms in contemporary Western Europe. In Rethinking European Welfare: Transformations of European Social Policy, edited by Janet Fink, Gail Lewis, and John Clarke, 207-230. London: Sage.

Cast net (2009). The dreams of transnational marriages. [In Chinese] <https://castnet.nctu.edu.tw/castnet/article/1583?issueID=64>.

David Campbell personal website (2014). David Campbell Asian Woman Womanizer from America. <Retrieved from: https://davidcampbellasian.wordpress.com/>.

Ekwakil, A. (2017). Reflections on intersections: Searching for an anti-racist, pro-migrant feminist response to sexual assault committed by migrants. Kohl, 3(1). < https://kohljournal.press/reflections-on-intersections>.

Hsia, H. C. (2018). From Foreign Bride to Taiwanese new immigrants [In Chinese]. <https://opinion.cw.com.tw/blog/profile/65/article/6575>.

Hsiao, H. H. Michael (2003). Taiwan and SEA: South Policy and Vietnamese Foreign Brides [In Chinese]. Taipeo: Center for Asia-Pacific Area Studies, RCHSS, Academia Sincia.

Kim, E. (2015). #StopDavidBond from harassing & sexually exploiting women in Asia. <https://www.change.org/p/stopdavidbond-from-harassing-sexually-exploiting-women-in-asia>.

Mobile 01 (2013). the phenomenon of xenomania of Taiwanese female on SKout [In Chinese]. <https://www.mobile01.com/topicdetail.php?f=292&t=3421428>.

PTT (2019). CCR板、ㄈㄈ尺板、真愛無國界板 [In Chinese]. <http://ptt.cc/>.

Ratskoff, B. (2018). Liberation Utopias: Houria Bouteldja on Feminism, Anti-Semitism, and the Politics of Decolonization. Los Angeles Review of Books. <https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/liberation-utopias-houria-bouteldja-on-feminism-anti-semitism-and-the-politics-of-decolonization/>.

Scott, D. (2008). China and the international system, 1840-1949: power, presence, and perceptions in a century of humiliation. NY: State University of New York Press.

Shie, S. T.(2009) . Masculinity and Desire Economics in Taiwan's Postcolonial literatures [In Chinese]. Journal of Taiwan Literary Studies, 9, 37-67.

Tomorrow news (2014). Hong Kong saw this video of westerners gaming their women and went berserk. <http://us.tomonews.com/hong-kong-saw-this-video-of-westerners-gaming-their-women-and-went-berzerk-2927513>.

[1] The solid social values of hierarchy in East Asia are derived from Five Disciplines (君臣父子), Four categories of the people (士農工商) and traditional Male chauvinism (男尊女卑).

0 notes

Text

追著,追尋遙遠的歸屬

自由與民主在生命中是理所當然。讀著課本中邁向民主進程的過程,息息相關卻如此遙遠,自由與民主給予我們意識說話的權力。而在秋意到來的日子,翻著幾週觀影後的隨記,思考並回憶著蒙古友人分享蒙古國邁入民主化的歷史,想著,於是翻起一張張旅行時的照片。

Photo by Hsiao-Chi Chu

猶記夢裡那廣闊的景色,馬兒在旁側奔跑,我坐在馬上,望著遠方,前方有牧羊人家在趕牛羊,孩兒在草原上嬉戲,夢著…… 軟綿的草依舊如此翠綠,我看著前方的太陽,追著,追尋遙遠的歸屬,心總是感慨,我的家。望著山、望著湖、望著遼闊的草原,夜晚冷冽,吐出陣陣的白煙,似夢非夢。

蒙古,極純粹的美麗

這段話,是2015年出版世界遺產叢書 — — 蒙古國的序言,循著記憶寫下對蒙古的感受,在記憶中,廣闊的大地帶來自由的氛圍。2014年開始,說多不多,說少不少,不自覺也去了四趟蒙古國。起初到訪為了探訪文化遺產,後續回訪則為了這片純粹自然不過的土地、真性情的友人們。只是,看似自由的蒙古,在開放前作為蘇聯的附庸國渡過了很長的一段時日。

幾週前,再次刷了《烏蘭巴托的搖滾現場》Live from UB (Lauren Knapp/2015/紀錄片/彩色/83 mins),蒙古作為蘇聯附庸國時 — — 蘇維埃共產主義時期,除了傳統民俗音樂,西方音樂文化為蒙古邁向自由民主扮演了潛移默化的關鍵角色。這部電影紀錄著自1970年代起,探索形塑自由現代化時音樂扮演的角色,如何成為蒙古國邁向民主的養分,傳播蒙古民族意識的媒介。透過紀錄Mohanik獨立樂團創作作品時,將傳統與西方文化融入音樂裡,如何透過音樂鍛造新的文化認同。

youtube

最印象深刻的莫過於1989年讓民主遍地開花的一首歌 — — Khonkni Duu,英文為The Ringing of the Bell,這鈴聲響遍整個蒙古,使蒙古民主的進程向前邁進。在2012年,更發表由12位歌手錄製而成的Khonkni Duu,以紀念民主化的過程。友人雖只是與我簡略的描述歷史,他說著自由經濟產生許多問題,但仍覺得比起社會主義時,現在更好,因能更有發聲/生的空間與權利。

‘Khonkny Duu’ Lyrics

I had a nightmare last night

As if a long arm tortured me,

Strangling my words and blinding me.

Luckily, the bell rang and woke me;

The ring of the bell rouses us.

The bell that woke me in the morning,

Let it toll across the broad steppes,

Reverberating mile after mile.

Let the bell carry our yearning

And revive all our hopes.

youtube

歷經民主化的歷程,現今的蒙古是一個自由民主國家。阿拉伯之春(阿拉伯語:الثورات العربية、英語:Arab Spring),又稱「阿拉伯覺醒」、「阿拉伯起義」後,開啟中東社會運動浪潮的興起。阿拉伯之春於2010年年底間,由北非與西亞的阿拉伯國家等發生一系列以民主與經濟為議題的社會運動 – – 一波革命浪潮。由於專制體制,部分國家民眾紛紛走上街頭,擴延至埃及、利比亞、葉門、敘利亞等國,似乎「一個新中東即將誕生」;但並非各國都成功轉型,邁向民主化的過程,卻也使得動亂與恐怖組織趁亂局崛起,進入長期戰亂之中,引發歐洲移民危機,稱阿拉伯之冬。如《藝術戰爭》(Art War)(Marco Wilms/2014/84mins)中紀錄了埃及藝術家如何透過藝術作為反抗政府的手段,喚起社會對公眾事務的關注,與推動公民議題的發展。

vimeo

民族、宗教信仰、傳統價值揉雜交錯的中東,伴隨著許多複雜情感。無論哪個地區、國度,民主化總伴隨著艱辛與漫長的過程,直至今日,因近代戰爭型態的改變、饑荒、社會結構改變等,人們仍不斷移徙,似乎永遠沒有終點。這股運動的浪潮還在持續著,風依舊在歐亞大陸吹著,領著自由的信鴿前往各處,響了一些鈴,人們依舊追尋、追尋遙遠的歸屬,希冀結成甜美的果實。

youtube

0 notes

Text

Discuss how ‘performative turn’ affects the curatorial practice and spectatorship of audiences in contemporary visual art exhibitions.

Author/ Chi Chu

In history, museums have played an authoritative and specific role/ framework in the process of the concretisation of artworks. Curatorial practices usually place exhibitions within the ‘white cube’ to highlight artworks or objects. This practice blends neutrality, objectivity, eternity, and sacredness and claims to be rational and transcendent while giving the artworks mysterious value and meanings. Nevertheless, since the post-modern period, critical museology has begun to discuss the concept of museums—'the space of interaction between the audiences, collections and exhibition space' (Crespo, 2006, p. 232) and the challenge to museums' power. As a result, the approach to curatorial practices in museums has become more diverse and inclusive. Also, the art field has been affected. Therefore, contemporary art institutions have been concerned about the performative turn, and the discussions of invisible stretchable boundaries existing in the functions of art museums. The 'guidelines' of exhibition space, curatorial practice, or artworks tend to have a transformation, gradually changed into different interactive or interpretation approaches. Therefore, this essay briefly discusses the transformation of art in history. Through two curatorial practice cases, this essay attempts to show how the 'performative turn' influences curatorial practice in exhibition spaces and the spectatorship of audiences.

Firstly, in terms of an overview of recent art history, since the 1960s and 1970s, Conceptual Art, Performance Art, Body Art, Fluxus and Happening Art have captured the performative actions and other related elements of daily life as a framework for art. This wave created conversations and fierce collisions over artworks, the artist's practising body, curatorial practices and the mechanized production of art museums. The performative turn of the contemporary art exhibition can be understood by considering performative art, which originated from the response to machinery in the industrial era. The 'body' (of artists or audience members) and interaction (inter-subjectivity) became the focus. From Bourriaud’s (1998) statements on relationship aesthetics, artists, through their artwork and the art process (in the making), attempt to reshape space and the spectatorship of audiences, and reverse the boundaries of public/private and daily/non-daily. Artists' artworks have challenged the sacredness of exhibition space and provoke museum visitors to recognise the importance of their existence to artworks. Examples include Christoph Schlingensie’s A Church of Fear vs the Alien Within (figure 1), the 2003 Venice Biennale, or a retrospective exhibition The Artist is Present (figure 2) for Marina Abramovic held by MoMA in 2010. Moreover, as Schechner (1988) states, the 'Fan' model (Figure 5) of performance spans the domain of traditional drama theory and adopts an inclusive definition of 'performance'. It means that the performance can include rituals/ceremonies, witchcraft, the outbreak and resolution of crises, daily life, gameplay, the art production process and ritualization (Schechner 1988). From these perspectives and cases, it can be seen that the performative turn in curatorial practices and artworks emphasises 'process', 'time' and 'ephemerality' (Li, 2018; Bishop, 2018). However, there is a critical concern to be resolved regarding how performance art is exhibited for a long period at museums. The common practice is to display the remnants/objects even if people are concerned that the live nature of performance art cannot be represented. However, it is useful precisely because it prompts recognition of the fact that the performance is no longer present and highlights the most critical feature of performance: ephemerality. Therefore, the remnants and the disappearance of performance art are mutually symbiotic (Li, 2018).

Secondly, as mentioned above, this transformation in art form has also influenced curatorial practices, use of exhibition space and spectatorship in art institutions. Hence, 'curatorial practices' have become an essential mechanism for understanding and analysing contemporary art, which has attempted to construct a situational, heterogeneous spatial space/form. The performative turn in curatorial practices and art exhibitions ought to be traced back to the exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form–words – concepts – processes – situation – information (figure 3), curated by Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) at Kunstmuseum Bern in 1968. According to an interview with Jens Hoffmann (MOCAS, 2013), this exhibition was the first to expose the concept in exhibitions and claim a new art spectacle and a new exhibition form from collective exhibitions at the time explicitly (Biryukova, 2017). For Szeemann, this museum was like a lab rather than a place of memories because Kunstmuseum Bern did not have any permanent collections at that time. Therefore, the experimental exhibition transformed into a place of art spectacle and the starting point for exploring the nature of art. A new curatorial and practising connection was created between artworks, artists, creative processes, exhibition space and curators, one which reconstructed the concept of 'acceptance of contemporary art/absence of curatorial mechanism Moreover, the 'attitudes' proposed by Szeemann refer to the representation of the artist's mental space, which is a process and artistic expression of the artist’s behaviours. It means that the making process of creating artworks is more critical than before. The artist and the artwork construct a symbiotic development relationship in the process of making. Also, the materials of artworks return to a free state. Due to the 'attitude' concept, the exhibition space becomes a practising space to visualise the artist's mental space and the creative process of artworks. For instance, Wrapped Kunsthalle by Bulgarian artists Christo and Jeanne Claude, wrapped up the museum building in polyethene and other materials (figure 3). During the process, artists have created conversations and shaped relations of intersubjectivity between museum space (building), artworks, and themselves.

Furthermore, one of the attempts of critical museology is to stimulate institutions to encourage more experimental process, practices and engagements (Shelton, 2011). In this exhibition project, Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form–words – concepts – processes – situation – information, Szeemann challenges the sacred image of museums, intending to make the exhibition space a medium, and produce the artist's activities in the making, including tangible presentation through various materials and intangible presentation of artists' attitudes, which is out of the existing display framework of the exhibition. As Foucault (2002 [1972], p. 54) states, discourse generates the objects of knowledge rather than only revealing and describing. This means that discourse produces forms of tangible and intangible seeing. As a consequence, in this exhibition, its discourse potentially not only generating but also establishing a new art form and exhibition/art discourse to present experimental curatorial practice because exhibitions and their spaces present the process of the performative turn through the transformation of not only the making process of artworks but also the interactions between artists, curatorial practice, and audiences.

Another presentation of the performative turn is live art happening in museum spaces, which can transform performance/behaviours/events with long-term ephemerality that extends the validity of works, and also transform the space-time perception of exhibition spaces. According to the concepts of live art (LADA, 2020; Joshua Sofaer, 2020), live art as a cultural strategy is different from the traditional contexts, which 'creates space for experimental and experiential attempts'. In live art, the notion of 'presence' is essential. Therefore, it can be encountered the actual moment of artworks in the making because either artist would do artworks in front of participants or participants would immerse in a created situation made by artists. An example of this is the exhibition Masingkiay by Taiwanese indigenous director Fangas Nayaw at the Museum of National Taipei University of Education (MoNTUE) in 2017 (figures 6 & 7). The concept of the art production is from a drama to a 'live art' exhibition. Hence, Nayaw aimed to create an indigenous gathering place in the museum where performers were hosts inviting audience members (guests) to engage in the social scene of the indigenous peoples (figure 8). The result was a participatory exhibition, as well as an example of the art process in the making. Additionally, Nayaw established the space as a home using a universal symbol rather than traditional indigenous totems or decorations. To break the stereotypes of indigenous cultures and traditions, this live art exhibition allowed participants to experience the diversity of contemporary indigenous cultures/customs and younger generations' transformation through the exchange and sharing of daily dialogue and affections rather than traditional indigenous dances. According to Bishop (2018), the dance exhibition is regarded as a model form of the new 'grey zone', and its performance form has surpassed the 'black box' of the theatre and the 'white cube' of the museum. The curatorial practise of Masingkiay re-discuss space transformation (function) from the theatre (performance) to the museum (exhibition) and how to create individual experiences for audiences (participants). In the process of the live art exhibition, artists, artworks, and audiences dissolve the time quadrant in the museum space, creating the new spatial sensory experience and open interactive participation. However, there are several questions mentioned in the curatorial process. The curatorial practice ought to concern about various perspectives, such as where the boundaries of the performative turn in this process are, when participants are performers can such a performance be regarded as either theatre or exhibition, how the curatorial perspective of performing art transform the art museum, and how live art drive the museum to form a social field.

Hence, there are several features of the performative turn in a live art exhibition. firstly, , the features of the performative turn not only highlight the transformation of curatorial practices but also liberate the framework of performing art from the theatre. Like the black box of theatres, the white cube of museums is an ideological space to present the ideas of artworks. Nevertheless, the presentation spaces of the live art exhibition, where the features of performing art, visual art and performance art coexist, are no longer an art museum or theatre. Meanwhile, performing art has emerged from the original context and creates extraordinary narratives. As Sheets (2015; cited in Defrantz 2018, p. 90-91) states, the relationships between the audience, artworks and artists which are practised at the museum space subvert the traditional discourse. The exhibition becomes a series of "scenes" (mise-en-scène), which means the curator develops the scenography so audiences can organise the context and perform in a specific time-space with the performers leading (Bal, 2008, p. 74), similar to the engagement process of Masingkiay. Furthermore, audiences must approach the artworks actively in the participatory art exhibition, not to mention the live art exhibition. Therefore, the features of approaches, rhythm, speed and points of view or focalisations of the audiences in the exhibition construct a sequence of meaning-making (Bal, 2008, p. 71). Consequently, when the discourse of the museum's curatorial practice changes, it further affects the characteristics of the space and the interactions between artworks, artists, audiences and spaces, rather than only concerning objects or artworks.

Furthermore, as mentioned above, different participative approach/ spectatorship implies that the audience can shape the relationship with the artwork in this kind of mechanism. Therefore, the interaction and the autonomy of audiences play a critical role in curatorial practice and the performative turn of exhibitions and artworks. To a certain extent, the audience also breaks away from the traditional linear interpretation of works of art. In psychology, the concept of suggestibility stated by Freud describes how those who appreciate art can only use intuition to feel the implied sensibility in artworks (Ferreira & Carrijo, 2016). However, the emphasis on body-oriented exhibitions, in response to the characteristics of 'process', 'time' and 'ephemerality', shows the transformation of spectatorship of audiences. A participatory art mechanism with the features of the performative turn can transform incidents that were otherwise difficult to control into actionable and recurring events. The nature of the ephemerality of performance can bring people together and produce dialogues. These dialogues are different from physical materials because dialogues are alive and intangible. It means that audiences have transitioned to 'in' the art process and have become a part of things. This gradually invisible sense of disappearance echoes the fleeting nature of the performance itself (ephemerality). As Kester (2004) states, art practice based on ‘experience’ is not only the situation and context of the presentation and creation of personal aesthetic experience, but also affects the audience (participant), from passive to active process, the construction of knowledge (in the making), discovery of reflexivity and intersubjectivity through involving body dynamics, and interaction and spectatorship between artists, artworks, audiences and spaces.

Overall, currently, the phenomenon of the performative turn in museums seems to be a trend. It is related to contemporary visual art discourse (institutions, curators, artists and more) because they have been concerned about the possibility of art, the potential of exhibition spaces and the spectatorship of audiences. The transformations of the performative turn have had many impacts on curatorial practices, museum spaces, re-performance of artworks, and how/what spectatorship intersects. The artists/curators and artworks construct an anomalous space and affect the audience's body, time and space while different 'live'/performative elements coexist in the same space. In addition to embracing the performative turn, it is also worth thinking about whether this type of art has brought about further changes to the museum under the contemporary context.

Figure 1: Christoph Schlingensie , A Church of Fear vs the Alien Within. Photo from https://venetiancat.blogspot.com/2011/06/54th-venice-international-art-festival.html.

Figure 2: The Artist is Present (figure 4) for Marina Abramovic held by MoMA in 2010. Photo from: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/marina-abramovic-marina-abramovic-the-artist-is-present-2010/

Figure 3 : Photo of Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form–words – concepts – processes – situation – information (https://contemporaryartdaily.com/2013/09/when-attitudes-become-form-at-kunsthalle-bern-1969/). Photo by Getty Digital collections https://rosettaapp.getty.edu/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2365335

Figure 4: Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Kunsthalle, Bern, Switzerland, 1967-68 Photo by Christo.

https://christojeanneclaude.net/projects/wrapped-kunsthalle?images=construction

Figure 5: Schechner's Fan model of performance (Schechner 2004: xvi).

Figure 6 & 7: live art exhibition 'Masingkiay', by Taiwanese indigenous director Fangas Nayaw in MoNTUE in 2017. Photo from MoNTUE.

Figure 8: The indigenous gathering place and engagement scene of 'Masingkiay' in MoNTUE in 2017. Photo by author.

Reference

Bal, M. (2008). ‘Exhibition as film’ in: Macdonald,S. and Basu, P.(ed.) Exhibition Experiments. Blackwell Publishing, pp. 71-93.

Biryukova, M. (2017). ‘Reconsidering the exhibition: When Attitudes Become Form curated by Harald Szeemann: form versus “anti-form” in contemporary art’, Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 9(1), p. 1-12.

Bishop, C. (2018). ‘Black Box, White Cube, Gray Zone: Dance Exhibitions and Audience Attention’, TDR: The Drama Review, 62(2), p. 22-42.

Bourriaud, N. (1998). ‘Relational aesthetics’, in C. Bishop (ed.) Participatory. London:MIT Press, pp. 160-171.

Christo (2020). Wrapped Kunsthalle by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in 1967-68 [Online]. Available at: https://christojeanneclaude.net/projects/wrapped-kunsthalle?images=construction. (Accessed: 1 May 2020)

Crespo, M. (2006). La museología crítica y los estudios de público en los museos de arte contemporáneo: caso del museo de arte contemporáneo de Castilla y León, MUSAC. De Arte, 5, p. 231-243.

Defrantz, T. F. (2019). ‘Dancing the museum’ in D. Davida, M. Pronovost, V. Hudon, and J. Gabriels (ed.) Curating Live Arts: Global Perspectives on Theory and Practice. NY: Berghahn Books, pp. 89-100.

Ferreira, D. D, and Carrijo C. (2016). Transference Management In Freud: An Analysis Of The Relationship Between Transference And Suggestion. Ágora (Rio J.), 19(3), p. 409-424.

Foucault, M. (2002 [1972]). The Archaeology of Knowledge. London:Routledge.

Getty Digital collections. Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form–words – concepts – processes – situation – information [Online]. Available at: https://rosettaapp.getty.edu/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2365335. (Accessed: 1 May 2020)

Joshua Sofaer (2020). WHAT IS LIVE ART?. Available at: https://www.joshuasofaer.com/2011/06/what-is-live-art/. (Accessed: 1 May 2020)

Kester, G. (2004). Conversation Pieces:Community+Communication in Modern Art. US: University of California Press.

LADA (2020). What is Live art? Available at : https://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/about-lada/what-is-live-art/.(Accessed: 1 May 2020)

Li, Y.-C. (2018). ‘From Black Box to White Cube: How MoMA Curates, Collects, and Arranges Space for Performance Art’ [In Chinese], Modern Art, 188, p. 6-22.

MoMA. The Artist is Present in 2010 [Online]. Available at: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/marina-abramovic-marina-abramovic-the-artist-is-present-2010/. (Accessed: 1 May 2020)

MoNTUE (2020). Masingkiay. Available at https://montue.ntue.edu.tw/exhibition-2017-dreamin-montue-2/ (Accessed: 1 May 2020).

Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit – MOCAD (2013). Jens Hoffmann Interview: "When Attitudes Became Form Become Attitudes" [Online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3JwXvOrxK5o. (Accessed: 1 May 2020)

Schechner, R. (2004). Performance theory. London: Taylor & Francis

Shelton, A. (2011). ‘From anthropology to critical museology and viceversa’, Museos y Territorio, 4, p. 30-41.

Venetian Cat (2011). Christoph Schlingensie , A Church of Fear vs the Alien Within. Available at: https://venetiancat.blogspot.com/2011/06/54th-venice-international-art-festival.html. (Accessed: 1 May 2020)

0 notes

Text

The sadness of Southeast Asian migrant workers in Asia

Author/ Chi Chu

It is difficult for migrant workers, especially illegal workers, to obtain a better life (Utopia) because of social values and inadequate migrant policy. This reaction paper considers how the restriction of individual sovereignty by biopolitics imprisons migrant workers’ bodies and features perspectives from Rodriguez, Graham, Puar and other scholars. The significant observation is that ‘the system of colonial racial differentiation established a modern hierarchical system through historical identities discerned by a new global structure of the control of labour associated with specific social roles’ (Rodriguez 2018:24). In some developed countries and regions of Asia, such as Taiwan, Japan, China and Hong Kong, as a result of racism and colonisation, Southeast Asian (SEA) migrant workers have faced discrimination and exploitation. Hence, this reaction paper will outline the phenomenon through Taiwan cases.

The interaction effect of gender and racism by global capitalism generates migrant policy as ‘a biopolitical tool of governance’(Ibid:21). It means that binary relationships, such as between insiders (citizens) and outsiders (migrants), are embedded within ‘social relations shaped by the long-term implications of colonial power’ (Ibid:35). This results in the classification of ethnic groups in the social structure. This situation has been observed in Taiwan. Numerous SEA migrants, including illegal migrants, have sought a better life in Taiwan because of higher wages. Migrants respond to the demand for workers prepared to undertake dirty, dangerous and difficult labour (the ‘3Ds’). Nevertheless, concern over the influx of SEA workers has grown in Taiwanese society because these workers have become one of the leading groups in the social structure. One reason is that migrant workers replace local citizens who are not willing to work for lower wages. As a consequence, the labour structure is redistributed. Another reason is that due to ‘moral panic’ (Hall et al. 1978, cited in Rodriguez 2018:17–18) caused by the media, the stereotype of impoverished and undeveloped SEA countries is exacerbated and ingrained in public perceptions and local society. Hence, SEA migrants are classified as second-class and labelled as inferior and uncivilized. The situation is similar to the one described in Resisting Borders: A Conversation on the Daily Struggles of Migrant Domestic Workers in Lebanon ‘there is no one listening to or helping migrant workers. Those workers labelled as the poor group experience discriminations and social exclusion’ (Gemma, Rose, Mala, Meriam, and Julia 2016). Thus it tends to be that the racial and class boundaries under social ideology enhance the discrimination of SEA migrants in Taiwan as well. Migrants’ bodies and actions are imprisoned by social consciousness and, as Fassin (2001:4) states using Foucauldian terminology, ‘the body has become the site of inscription for the politics of immigration — biopolitics of otherness’.

Furthermore, the phenomenon of exploitation and physical maltreatment is on the rise, especially in the Taiwanese fishing industry, not only because of social values and stereotypes about SEA migrants but also because of Taiwanese migrant policy — ‘Regulations on the Authorization and Management of Overseas Employment of Foreign Crew Members’ (FA, 2019). Taiwan, as the biggest distant water vessels economy in Asia, has an oligopoly of the whole trade from catching yield to the employment of fishery workers. Also, it is one of the leading countries in the trafficking of illegal SEA migrants. In 2018, the documentary Exploitation and Lawlessness: The Dark Side of Taiwan’s Fishing Fleet, filmed by the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), not only revealed that Taiwanese distant water vessels plunder the ocean’s resources but denounced the trafficking of illegal SEA migrants in the Pacific Ocean. The documentary also highlighted the fact that issues of maltreatment and exploitation are hidden in sophisticated transnational illegal trades. There are two factors that cause dehumanisation. Firstly, the systematic classification of fishery workers is the result of racism and colonisation. One agent (cited in The Reporter in 2018) said, ‘we buy cheap and obedient fishery workers from the margins of the world, such as Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand’. Fishery workers are classified by ethnic group and purchasing price. Also, according to the captains’ training book produced by the Fisheries Agency (FA), fishery workers are classified by nationality and ethnic characteristics (Ibid). Some description in the training book portrays Indonesians as less able to adapt to hard work compared to Vietnamese. These classifications not only enhance racism through subjective evaluations of different ethnic groups but also present southern countries (southeast Asian /fishery workers /poor) as colonised and oppressed by northern countries (Taiwan /captain /wealthy). These inequalities discipline fishery workers’ bodies.

Secondly, the conditions for and treatment of fishery workers on the sea are described as inhumane. According to the documentary by EJF(2018), migrants are mistreated or beaten savagely like animals and cannot receive a regular salary because employers dominate all resources. The purpose of exploitation or maltreatment is ‘maiming manifested’ (Puar 2017: 129). Puar (2017:52), studying a similar situation in Palestine, states, ‘it is another aspect of this biopolitical tactic that seeks to render impotent any future resistance’. It will be seen from this that most fishery workers have difficulties redeeming themselves or leaving the boats because of a lack of sovereignty and resources. As a result, workers stay on the sea for their entire lives. Inequality and inhumanity imprison and maim fishery workers’ bodies in an endless vicious reincarnation.