Text

Spice Up Your Life, It’s Good For You

Ah, spices… They can give depth to any dish by enhancing its flavor. But they also have a variety of functions beyond improving taste. Not only are spices are valued for medicinal purposes, but also because they kill food borne microorganisms by inhibiting toxin growth. Before I explore, analyze, and discuss the role of spices within the context of food and culture in the D.C. area, I should first begin with a definition.

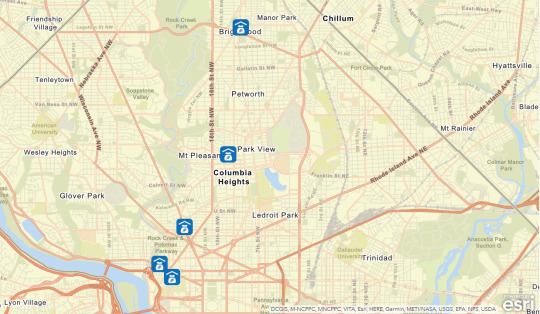

For this project, I visited five grocery stores- Whole Foods, Trader Joes, Safeway, Streets Market, and Capitol Supermarket- in the Northwest area of D.C. and did optical observations and analysis on commodity of my choice: spices. In my first blog post, I purposely did not define spices in order to avoid confining my optical observations and field notes to align with a particular definition. But it is now time to address and define this subcategory of food. In the literature, most scholars seem to agree that “the term spice refers to any dried plant product used primarily for seasoning, be it the seed, leaves, bark or flower” (Pepping Up Production 2009, p. 8). Furthermore, “each spice has a unique aroma and flavor that derives from ‘secondary compounds,’ chemicals that are secondary (not essential) to the plant's basic metabolism” (Sherman & Flaxman 2001, p. 142), which are important components that contribute to the enduring value and function of spices.

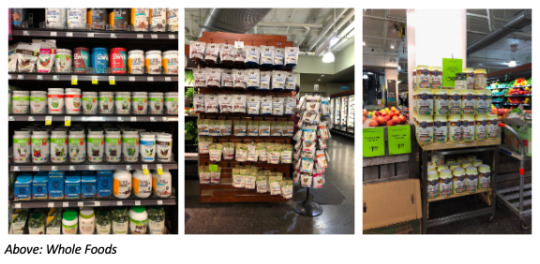

If one of the functions of spices is to kill toxic microorganisms, which subsequently protects humans from food-borne disease, it is no wonder that spices are so popular and high in demand across the world. This importance became evident in my fieldwork through the sheer quantity and selection of spices in the five grocery stores I explored. The five sites, which were all located in the Northwest area of D.C., all differed in their spice selection, pricing, packaging, and location. While the variety and amount of spices differed across all five grocery stores, each one contained an aisle, or section, exclusively for spices and seasonings. One overarching and consistent observation had to do with the amount of space dedicated to popular and commonly used spices, such as garlic powder, allspice, oregano, cumin. In all five grocery stores-- Whole Foods, Trader Joes, Capitol Supermarket, Streets Market, and Safeway-- at least one of those listed spices was in abundance and easily identifiable within the spice aisle (placed at eye level or spread out across one row). Unsurprisingly, this is not random. According to Sherman and Flaxman’s (2001) research, who predicted that spices used in cooking should exhibit antimicrobial activity, “the four most potent spices- garlic, onion, allspice and oregano- killed every bacterial species tested,” (p. 143) which was evidently reflected through the volume and space dedicated to those particular items in the five grocery stores I visited. What I initially believed was a ploy to entice customers to buy larger quantities of basic yet essential spices was actually consistent with the finding their potency is extremely effective in killing toxic bacteria found in food and other spices.

Another consistent observation across all five supermarkets was an overall emphasis and preference for selling organic spices, which I didn’t quite understand until I began reading about spice contamination. Contamination in spices can occur in a number of ways, one of which is through mycotoxins (mold), especially if a spice is dried on bare ground (Pepping Up Production 2009, p. 9). Additionally, spices like coriander, paprika, and chilis can also become contaminated through storage pest infestation (Pepping Up Production 2009, p. 9). In order to avoid pesticides and/or chemical contamination, organic spice farmers dedicate/spend additional time and energy (getting certifications, partnering with producers, shorter harvesting periods, not drying their own spices) to ensure the proper growth, quality, and packaging of their spices prior to exportation (Pepping Up Production 2009, p. 8). This phenomenon thus explains and is consistent with the price spike that accompanies most, if not all, spices labelled as organic across all grocery stores, especially in Streets Market, where organic spices were twice as expensive as in Whole Foods or Safeway.

Something that increasingly perplexed me as I visited the grocery stores was the relatively small amount of spicy or hot spices sold, such as curry powder (it was stocked but with little to no variety), aleppo pepper (did not find in any store), cajun (only sold at two of the five grocery stores!), chiles (most grocery stores sold it but the variety was underwhelming), or berbere (only at Whole Foods). After reading Sherman and Flaxman’s research (2001), who postulated that “the use of spices should be greatest in hot climates, where unrefrigerated foods spoil quickly” (p. 144), the lack of hot spices began to make sense given Washington D.C.’s climate and geography. Located in a humid subtropical zone characterized by cold winters and hot and humid summers, Washington, D.C. is not subject to immense contamination or spoilage, which might explain the relatively low presence and variety of spicy spices sold in various grocery stores, and that’s not accounting for the increasing presence of foreign populations. Capitol Supermarket, for example, was one of two grocery stores (the other one being Whole Foods) that included an immense selection and variety of hot spices for its customers, which may reflect the presence and cuisine preferences of Latino populations in the area.

Unlike Whole Foods, Capitol Supermarket, and Trader Joes, Safeway and Streets Market were the two most ‘neutral’ stores in the sense that they didn’t seem to cater their products and prices to specific populations. Given the selection, location, arrangement, and pricing of the grocery stores and their spices, I gathered that the Capitol Supermarket spice selection is tailored to Latinx groups and people of lower socio-economic status (cheap pricing, wide selection of Central and South American spices); Whole Foods spices are for avid home cooks and foodies, college students, and individuals from higher socio-economic status (ethnic and organic spices, medium to high pricing); and Trader Joes spices are for college students and individuals who don’t have time to prepare and cook elaborate or complex dishes (cheap pricing, small quantities, little spice variety). By contrast, the spice selection in Safeway and Streets Market did not seem to have selections tailored to particular populations or cuisines, although one could argue that the ridiculously overpriced spices in Streets Market are not affordable or economically effective for populations of lower socio-economic status.

Food, which is essential for survival, is also deeply embedded in culture, identity, customs/practices, history, health, geography, and lifestyle. Spices, which are a small but significant feature of food preparation and consumption across the world, provide a window for studying food and culture by revealing underlying social, medicinal, and sensorial functions and values of seasonings within a particular society, community, or group. While this fieldwork project exclusively focused on the distal (receiving) end of the food supply chain, i.e. grocery stores, I gained a lot of knowledge almost exclusively through optical observation, which allowed me to make sense of a variety of questions and topics I address in this culminating piece.

Works Cited

Sherman, Paul W. and Samuel M. Flaxman. “Protecting Ourselves from Food: Spices and morning sickness may shield us from toxins and microorganisms in the diet.” American Scientist, Vol. 89, No. 2 (2001): pp. 142-151. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27857437

“Spices: Pepping up production.” Spore, No. 141 (2009): pp. 8-10. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24343555

#spices#TheFinale#OverviewEssay#anthropology#culturalanthropology#anthropologyoffood#researchproject#WholeFoods#TraderJoes#Safeway#StreetsMarket#CapitolSupermarket#WashingtonDC#Northwest#GWU#opticalresearch#culture#allaboutfood#ANTH4008#CassieDestremau

0 notes

Text

The Essential

Many foods’ journey is disconnected from the human experience; where they are grown, how they are processed, where they are sold, who buys them, and leading up to their shelve-life in a grocery store where humanity comes in contact with them. Some people are passionate about their food, thus food enters a more social relationship with humanity rather than a nourishment role. Robin Fox describes “food fashion” as a way to explain the passion people feel about their food at a certain point of time that results in food fads. Fox describes how food snobbism essentially elevates food fads to a point where if you aren’t informed in them, you are considered a social failure. Also, much like the fashion industry, food fashion is dependent on change and people are often captivated by these foods in a fleeting manner (2014).

The focal point of this research aims to take reverse food snobbery, “a cultivation of proletarian tastes as long as they are romantic,” to the next point of opposition of food fads (Fox). A complete rejection of food fashion “in’s” and “out’s” and a focus on a commodity above it all; one in which embraces simplicity and necessity, cooking oil. This commodity in a grocery store is essential to practically all the food one eats. Cooking oil is not apart of the war of food fads versus common foods; rather it reflects all social hierarchy, or so I may have believed. I aim to uncover if an item, crucial to almost every modern diet, truly has the ability to manifest in a non-romantic collectivism interaction with humanity and their food. Could cooking oil, quite possibly be the thing that humanity has in common all along?

For the purpose of this research cooking oil is defined as plant, animal or synthetic fat used in cooking that may be used in food preparation and flavoring, but is not solely used for this purpose. The cooking oil in this optical research focus differs from edible oil which is exclusively used for flavoring. Therefore oils such as truffle oil, or any other flavored oil that appears in the research are classified as edible oils and will not be analyzed extensively. Major cooking oil varieties include; olive oil, extra virgin olive oil, coconut oil, sesame oil, peanut oil, vegetable oil, corn oil, canola oil, grapeseed oil, avocado oil, sunflower oil, and safflower oil. The reason is mainly because, cooking oil reaches the essence of customary that the flavoring oils do not share. The price of truffle oil alone reveals that the intended consumer is of a higher class or one willing to allocate a large portion of their budget towards an oil.

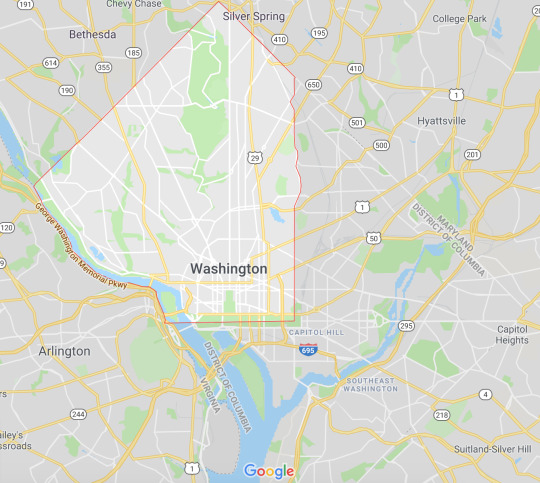

For my field visits I went to five different grocery stores in Washington, D.C. and they included; the Whole Foods Market located in Foggy Bottom, Trader Joe’s in the West End neighborhood, The Mediterranean Way Gourmet Market in Dupont, the Giant Food in Columbia Heights, and the Walmart Supercenter in Brightwood. The pattern I wished to follow in these five locations was a general direction north (map) and to the benefit of my research, each location had a supply of cooking oils. Though, not every location offered the same kind of cooking oils.

In five store optical research it is difficult to find similarities in such different stores from different neighborhoods about a product that runs consistent. The packaging, is however, a rather consistent particular similarity. Each store had some kind of glass or can packaging. The glass bottle packaging was always reserved for at least the olive oil in each of the grocery stores. Some grocery stores used the glass bottles for safflower oil or grapeseed oil. Often times glass bottles indicated a higher price, the only time where this could not be proven was the gourmet market because they had no comparison.

However, the gourmet market in Dupont had higher prices overall which could equate to the fact that since all their oils were in glass or cans, then they maintain the type of packaging elitism found. Glass packaging requires less energy to produce than the plastic packaging. Although glass is more expensive to produce, plastic is more expensive to recycle. Plastic also, has the possibility of leaching toxins which is a risk that can be avoided if one someone has the dispensable income to spend on not just the oil, but the packaging.

Another major similarity across all the stores was the presence of olive oil at each one. The packaging varied at each location, but olive oil was very consistent and also consistently was the product with a few taken from the supply of it. Some products had not a dent in the supply, but olive oil always appeared like someone just came by and picked some up. However, every time I was observing the oils, there was never more than 3 people around. Although, no one seem to stick around the oil section long, it only proved my point further. The oil is already a well known and trusted staple that the glamorization of the product does not need to be done. It is a given.

Differences were far and wide when it came to oil types; variety, packaging, pricing, location, people. However, something to note is how each store caters to its particular demographic. Whole Foods offered the largest selection of ghee I saw out of every store, and that probably has to do with the wealthy food fashion chasing people they hope to attract. While Trader Joe’s instead offered suggestions paired with each oil on the label, that gives you the friendly good-ole-Joe feel that the store wants you to have. The gourmet market really only had an extensive collection of extra virgin olive oil, because they were focusing on products from a particular region. The Giant had the largest selection of peanut oil, which is often used to fry food, which appeared the cooking style of the demographic they wished to serve. Lastly, the Walmart had the best price and largest quantity of canola oil, most likely because their demographic mainly used this.

Across the cooking oils; olive oil had the largest range on price and packaging, but people chose to buy it. Every time, people always bought olive oil. There was an olive oil for whatever type of person you were. However, my last two grocery store visits showed canola/corn/vegetable oil can serve this purpose too, but for those with a desired lower price point overall. However, it seems to be less about the price when it comes to essential items and at a times more about the type of Whole Foods/Trader Joe’s mindset, which prioritizes healthy and organic living over price. At times this means those who are wealthy can partake, but also those with maybe a lower income may want to partake as well because they share that mindset.

Reference

Fox, Robin. “Food and Eating: An Anthropological Perspective.” Social Issues Research Institute. 2014. http://www.sirc.org/publik/food_and_eating_0.html

#oil#cookingoil#oliveoil#canola#corn#vegetable#grapeseed#peanut#avocadooil#sunflower#wholefoods#traderjoes#gourment#market#giant food#walmart#elitism#packagingelitism#extravigin#essential#diamondintherough#ghee#fashionfood#foodfads#commongood#social hierarchy#GW#culture#anthropology#anth4008

0 notes

Text

A Food For all People: The Story of DC Sausages and the People that Buy Them

Like the offering of sausages at a cookout, all good things must come to an end. This is the end, a wrap up of five blogs on the sausages of DC. Read them if you would like, ignore them if you don't; both are equally good options. This short little paper will sum them up, more or less, so it serves as a third option for those that would take it.

The sausages of DC were, in my opinion, a very fun thing to study. With that being said, I didn't do it very well but it is what it is. The story I originally set out to tell was on gentrification in DC. This story, however, has yet to be told through sausages by me in these blogs, nor I assume, through anyone else's. It should be told.

The stores I have visited seem to cater to the same sort of people. People that have a couple of extra bucks to toss around. To tell the story of gentrification I would have had to visit markets that I would not normally go to. In this respect, I failed. I didn't even try.

Gentrification is, of course, a widely acknowledged reality in DC. How could it not be? We have Union Market, The Wharf, and every new six-story luxury-condo complex as it's billboards. Though gentrification is not a black and white issue, the rise in demand for housing and it's consequent inflation of rent has hurt many who have called DC home for generations, especially the black community. To summarize Chef Kwame Onwuachi; Harlem had it's renaissance, DC never needed one (Onwuachi, Notes From a Young Black Chef).

Though some of the shops I visited were diverse in terms of age, gender, and race, I was never once a minority within the confines of its walls or the neighborhood that it was in. I explored the expensive DC and with that, saw only the expensive sausages.

I first traveled to Whole Foods. The majority of the foods, sausage included, are displayed in the lower, basement level of the Foggy Bottom Whole Foods. Coming down the escalators directly in front of the automatic glass entrance, and taking a left at the tangerines, I found myself in one end of the meat section. To my left, the butchers counter; to my right, a row of open-faced refrigerator units filled with various offerings of meat. On the concrete floor between them is an open-faced cooler, filled with ice, displaying even more meat. The whole ordeal is lit with stark white lighting which gives a cold but clean feel. A faint smell of fish perfumes the air (the butchers and fishmonger stations are side by side) but that is not necessarily a bad thing. Compared to the rest of the store, the space is relatively barren, almost clinical. With that being said, the 15’ by 25’ space is a practical, to the point kind of place.

Sausages are found in the butcher's display, the central coolers, and the open-faced refrigerators. The butcher display has a large variety of “made right here” pork sausage in between the thick cut steaks and fresh-ish fish; Bratwurst, German, Andouille, Habanero Green Chili, Sweet Italian, Mild Italian (with and w/o casing), Maple Breakfast, Country Breakfast, Bulk breakfast-sage (w/o casing), and Spicy Italian (with and w/o casing). They also have; Chicken Bratwurst, Mild Italian Turkey, Hot Italian Turkey, Sweet Italian Chicken, and Spicy Italian Chicken. All are displayed in an orderly manner; the links are aligned and the patties are pretty.

Next, I went to Trader Joe's. The sausage section at Trader Joe’s sucks. First of all, it’s mostly chicken sausage, which any lover of sausages knows to be inferior to their pork filled peers. It is also right next to the “fully cooked, uncured bacon.” Anthony Bourdain once said a cook doesn't deserve garlic unless they’re willing to peel it. With this rule in mind, I hope he would approve of my following statement: if you can't cook your own bacon, you don't deserve to eat it. Besides that, the section is quite small, but it seems to get the job done (again… only if you like chicken sausage).

After that disappointment, I shipped myself off to union market. They charged 12.99 for a pound of pork sausages. That about sums it up.

Finally, I made it to the holy land; Stachowski’s Market. The sausage selection was extensive. Some were found in the butcher's case, but a majority were found in a stand-up freezer off to the side, opposite of the cash register which sat in the middle of the floor. Much of the sausage behind the counter was priced at $10.99 per pound. To be fair, they looked worth it. Portuguese Linguica, Smoked Kielbasa, Hot Italian; these were all out to be bought.

The shop itself is little but filled with people, often in groups grabbing a little lunch to eat in or take out. Most were white, many I assume, live in Georgetown. There are two tables against the windows and a couple of shelves stocked with delicious, though unaffordable goodies. The magic happens behind the counter where the meat is cut and the sandwiches are prepared.

To my sincere surprise, I found myself going back to Whole Foods for my final observance. Whole Foods, as it turns out, does some pretty decent sausages at a pretty decent price. This did not change my opinion of the place though. I opened my first blog saying that the supermarket chain is a detriment to society. I stick by these words, and you should too.

References Cited:

Onwuachi, Kwame. Notes from a Young Black Chef: A Memoir. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2019.

#anth4008#anthro#DC#gentrification#eggsbacongrits#thecheapcuts#sausage#foodgasm#food#expensive#gw#essay#blog#Notesfromayoungblackchef#done

0 notes

Text

A Watery-Than-Thou Complexed Finale

Welcome, and thanks, for holding your head above water for my last presentation on the item itself! It is quite an essential, and very vital one, to have. And it serves to hydrate us, to nourish us, and to replenish us. In fact, it is so necessary that we need it just about every day. I for one saw the importance in water and wanted to partake in it as my research for this class. Our bodies are made up of roughly around 60 percent water according to ACT Government (2016), and that alone says a lot about why it is just needed. Why it’s wanted is a whole other, yet similar, story.

I originally came across the idea of choosing water as my food item alongside orange juice. I didn’t know what to do until I really thought about what was more ‘resourceful’: water is depended on heavily since it provides moisture, repair and protection, and regulates body temperature (Mayo Clinic, n.d.). So, of course I had to choose something that simply was powerful enough to be its own complex. And is its own complexity. Furthering my earlier point, I wounded up choosing water as the item of choice due to its importance—no shame towards orange juice though.

My very first site I went to was the wholesome Whole Foods. The intentions for this site were to initiate the food project, as well as to see the variety the store had to offer. Really as being the first, Whole Foods set a rather high standard for the remainder sites. I first entered it on February 7th around 11:10 am, right after class. It was getting closer to Valentine’s Day, and Whole Foods had made sure it was known. I walked the top floor and saw the first brand of water, Starkey. They were stacked neatly on top of each other with glass shelving. The red labeling reminded me again that Valentine’s Day was around the corner. What I found out next was that not only did Whole Foods have a plethora of water, it was the epicenter of all the sites.

Downstairs was where the main action was at. I would say this store had between 20-25 brands of water alone. On top of that there were several different flavors, which was a prime factor for making Whole Foods a unique site. The next store would justify this reasoning.

My next site was the CVS not very well-known, which resided at the National Harbor. I had visited this one on February 17th, around mid-day while the anime convention, Katsucon, was happening nearby. It was quite the catastrophe in comparison to Whole Foods. This site had just about half the brands, and even less than a quarter of the flavors, as the last one. It was pretty much a desert when juxtaposing the two sites, but it made sense. A couple thousands of people who came to the convention were within the area and would of course need supplies to survive the weekend.

I had entered in the midst of a ‘valley’, around the time not too many individuals were there, with the exception of some stragglers here and there. I recall seeing the majority of their water section to the left of the entrance, in the same aisle as the soda. The majority of the waters here were in packaging, or what I call ‘bulks’, yet also consisted of individual, grab-and-go’s that sat on the very top shelf. CVS also had two refrigerated water sections, where one was in the cold foods’ aisle and one near the self-checkout line. This site was uniquely emptied out but for good reason. Yet because of this lack in both variety and selection, it made it stand out.

For my third site, it was at least somewhat comparable to Whole Foods. I visited the Walgreens on F and 12 St., NW near my job at Madame Tussaud’s, on March 19th. Right before my shift I walked alongside its windows on F street and immediately saw where the water would be. The entrance is on 12th street and once entering I went right for the soda aisle to the very righthand side of the store

I find that though there is a common pattern of water being in the same aisle as soda, and even wine in Trader Joe’s case, wouldn’t there be an explicit sector of each store for solely water? Or am I overthinking?... Anyways, I would have to say Walgreens had their thirst-quenching game on point. It was perhaps one of the most comparable, with Safeway, to that of Whole Foods. And if I do say so myself, the brand of nice! added a nice touch to the scheme of things. I would say that this site had at least half the brands, if not three fourths, of the brands that Whole Foods had. And around a quarter of the flavors, maybe even a little bit more, that it had. But, similarly to CVS, Walgreens too had both a chilled section and a dry section of water. The latter of which one could see through the window.

What distinguished Walgreens as a site was the fact that it had complements to the item which were displayed frankly right beside it, and near it. This one had included reusable water bottles as a complement, juxtaposed to CVS that only had water-flavoring next to the product. The next part included the cold aisle which was when I took a left and kept straight out of the soda aisle. Walgreens was somewhat well-stocked in terms of cold water, so I could not complain too much. Yet for its final portion, when I thought I was through, it surprised me by having grab-and-go’s in between sunscreen and protein and snack bars. And this was closer to the entrance—that I had not noticed!

Each site presented itself with something new. One way or another I was going to find out a new fact about water, what we can make out of it, and so forth. I especially got to learn something new at my next site, Safeway. With this particular one I was pretty much aware of the ins and outs of the store. I was raised in it so the hunt for water was simple. As with the other sites, the water resided in the same aisle as the soda. To get here I had to enter and keep straight until the chicken stand and make a slight left and then slight right. Thankfully Safeway provides both the aisle number and score of what is in that aisle.

I found that this site had a lot more yellow tags on its products than any other store. But it was it made sense ultimately because of the closing of the Safeway. The water was on the righthand side of the aisle, way past the sodas. Their flavored water drinks were mixed in with the tonic and seltzer water, and with the sodas and flavored drinks. Safeway kept a separation of those and the plainly flavored water especially through gaps here and there on shelves.

The majority of the water was made up of the bulk packaging. There were several different brands such as Deer Park, Poland Springs, and so forth, that were included. But what struck me was the fact that this site had ‘baby’ water, or that of which is used to mix with formulas so that the baby is able to feed. It also included children’s water, whereby they had the sized bottles that children could grab and go and drink themselves without much assistance.

Finally, I came across Trader Joe’s. Now I really never been here before, but I’ve heard the hype. I came here right after class and knew I had to join the cult that was Trader Joe’s. With high hopes, it was going to be one of the best sites. But really it was the opposite—insofar as that the ambiance gave me the chills. Once entering the site, I did have to take a moment or two to find the water. I came to find out that it was surrounded, and outdone, by their endless wine section that stretched into the soda aisle. I was pretty amazed by not only the environment I had entered, but also by the fact that booze was a thing at Trader Joe’s. I would have to say that that made it stand out among the sites. But let’s not forget prices! Whole Foods couldn’t even beat their 69 cent liter bottles of water.

So there you have it. Hope you enjoyed the journey as I have, and let’s talk real soon!

--Jamie Elliott

Works Cited

1. Functions of water in the body. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/multimedia/functions-of-water-in-the-body/img-20005799

2. Content-Approver. (2016, April 13). The importance of water. Retrieved from https://goodhabitsforlife.act.gov.au/kids-at-play/importance-water

#Water#Whole Foods#CVS#Walgreens#Safeway#Trader Joes#ANTH 4008W#Foggy Bottom#gwu#washingtondc#sociocultural anthropology#anthropology#cultural#ethnography#optical research#Flavors#plain#sparkling#Brands#Fiji#More wine than water#retro#groovy#Jamie Elliott

0 notes

Text

Soy Sauce: Salty Misconceptions

As an Asian American woman, I have grown to connect with and appreciate my heritage through food. While I enjoy fried chicken and steak, I also enjoy having a nice bowl of 牛肉面 (niu rou mian=beef noodle soup) and 米粥 (mi zhou= rice congee). Despite indulging in both American and Chinese cuisines, I was brought up with the notion that to have real Chinese food, one had to go to Asian grocery markets and Chinese restaurants. Simply put, going to Panda Express or Walmart was a sin in my house. For my anthropological fieldwork grocery project, I chose to investigate how soy sauce, a preconceived international food by Western consumers, is marketed on American shelves.

Soy sauce (shoyu in Japanese) originated in China roughly 2,200 years ago and is believed to have been introduced to Japan by a Buddhist monk in the mid-13th century (Stein and Shibata). It is made from soybeans, wheat, salt, and water that is fermented in a four year process. The ingredients are not the make it or break it of a good soy sauce, but rather its production environment. Traditional Japanese brewers use koike or specially crafted wooden vessels to ferment the soybeans. The grains of the wood enrich the millions of microbes that deepen the fermentation to produce a savory umami flavor.

However, most modern-day soy sauces are produced within stainless steel vats that shorten the multi-year fermenting process to just three months. Because the bacteria produced in koikes cannot survive in steel tanks, many commercial companies pump their soy sauces with additives like monosodium glutamate or MSG in order to keep up with the demand and production of soy sauce--something I would discover to be true during my project.

During the spring of 2019, I examined soy sauce brands across 4 grocery stores in the Washington, D.C. area. My research was conducted through participant observation, which involves walking around the store as a potential customer and observing the ambiance of the store and its customers, while taking note of the location and sensory details of the soy sauce options offered. I conducted optical research as I observed my surroundings without personal interviews. Over the course of a semester, I learn that soy sauce, in its labeling and aisle surroundings, has been modified to fit into Western perceptions of Asian cuisine--revealing deeper connotations behind its ingredients and authenticity.

My first store visit was at the Whole Foods Market in the Foggy Bottom campus of the George Washington University. I paid close attention to the logos of each brand, nitpicking the logos for its embodiment of Asian culture through symbols like bamboo shoots and cranes. I later observed the design was not the most striking element, but rather the emphasis on reduced sodium and non-GMO ingredients.

Every bottle addressed it through writing, logos, or both. Health reasons aside, I came into this project with a preconceived notion that buying soy sauce from an American grocery store equated to not only buying from a market that addressed negative connotations of an Asian cuisine but also one that implied Chinese manufacturers were careless for placing MSG in their products.

Talk of Asian cuisine being too salty or not healthy for consumers was rarely discussed in my family nor did Asian food markets I went to as a child address it in the labelling. Seeing this language on American-brand soy sauce bottles made me feel culturally isolated as someone who had Chinese food almost every day of her life.

I visited Hana Japanese Market to see if the same language of reduced sodium appeared on its bottles. Hana Market is on the first floor of a quaint gray townhouse in a quiet neighborhood on U Street. I not only found Japanese-imported soy sauce on the bottom shelf, but also the American brands with reduced sodium and non-GMO stickers were on the shelf above. I was shocked to see the overall bottom placement of a renowned Japanese seasoning staple.

I wondered if it was because Hana’s store owners tailored their products towards the perceptions of Western customers--fully aware that MSG was a health concern and they had made efforts to address it. They even printed out English labels that said reduced sodium for the bottles written in Japanese. On an eye-level shelf, Hana offered ponzu or citrus “seasoned” (not flavored) soy sauce. I had never heard of ponzu until this site visit. To see traditional and authentic Japanese products at Hana made me feel more part of the Japanese culture and where we were borrowing this Asian cuisine from.

Visiting Safeway and Streets Market was a pivotal point in my research. The Safeway I visited in Georgetown was a superstore that focused on convenience and value. However, I was quickly appalled by the selection of soy sauces at Safeway. The soy sauces at Safeway were found in the “Asian/International” section. In the collage below, Safeway had big jugs of soy sauce that reminded me of gallons of gasoline. All options had cheap prices of $2-4. While the prices were tempting, La Choy proved that the quality was not worth it.

The bottle said “Inspired by Traditional Asian Cuisine”, yet its ingredients of hydrolyzed soy protein, corn syrup, caramel coloring, and potassium sorbate (a preservative) were quite the contrary. Might I add it was also produced in Omaha, Nebraska. After seeing the natural and traditionally brewed bottles that Whole Foods and Hana offered, La Choy was an insult to the traditional Japanese soy sauce brewers and the Asian culture itself.

Streets Market revealed a different connotation to how soy sauce was marketed. The store was located in a busy part of D.C., near the border of the Northeast sector. Prices at Streets were sky-high, yet the instant ramen noodles and ready-made “Asian” meals surrounding the soy tiny bottles of soy sauce did not portray Asian food as appealing. Streets perceived Asian food as an on-the-go and quick bite rather than a cuisine to be appreciated.

Perhaps this perception was why it took me 3 stores to locate a place with more than one type of soy sauce. Prior to Streets, I visited Trader Joe’s, Dean & DeLuca, and GWU’s Gallery Market only to discover they had one option. A bottle of soy sauce is not something to be consumed in a day, but I expected more variety. After my visit at Streets, with its array of plastic bowled and preservative-filled instant noodles, perhaps the purpose of soy sauce to Western consumers was nothing more than just a condiment that was put on things to make them saltier.

I went back to the Foggy Bottom Whole Foods for my final site report and was glad to see the wide selection of soy sauces with no worries of added preservatives. It gave me a greater appreciation for the store’s strides towards lower prices and high quality standards.

Above all, the Asian culinary identity was present in its surroundings and labelling. The International aisle lived up to its name as the soy sauce was next to Asian ingredients rather than instant bowls of ramen. Offering actual ingredients encouraged customers to make Asian dishes themselves, allowing for a greater appreciation of the Asian culture they are consuming. The labelling of bottles like San-J educated customers on the usage and meaning behind soy sauce.

My fieldwork has lead me to draw two conclusions on the implications surrounding the culture of Asian food in America. First, Asian cuisine is modified to fit the tastes of the” average American consumer”. Dishes like Kung Pao or General Tso’s chicken would never be found in China. When Panda Express was established in 1983, the Cherng family knew it would be difficult to for mainstream American customers, especially outside of metropolitan areas, to accept a Chinese dish in its original form and flavor (Liu, 138). Although its original flavor was salty and spicy, Andrew Cherng invented a new sweet and spicy orange sauce for chicken which allegedly came from Hunan cuisine in South China.

In addition, the famous P.F. Chang’s restaurant chain was named after restaurateurs Peter Flemming (PF) and Philip Chiang. However, “Chiang” was purposely changed into “Chang” in order to make the brand less foreign to the American public (Liu, 130). For many years, authentic Chinese food has had no market in America--pointing to a dangerous conception among many Americans that Chinese product owners are not in control of their own culture in the American food market. At the same time, food is both a culture and commodity. When food becomes a commodity, it is no longer an inherited culture as corporate America can easily appropriate it from the Chinese community (Liu 135).

Second, the use of MSG instead of soybeans in soy sauce points to a loss of authenticity in Japanese culture. The health dangers of replacing soybeans with artificial flavoring first occurred in the mid 20th century when Chairman Mao seized control of China in 1949. Perceptions of the Chinese changed as they were seen as threatening to US democracy. The association between Chinese food and health problems was an easy connection for Americans to adopt the Chinese Restaurant Syndrome or CRS (Germain, 2). People complained of having numbness in the back of the neck that gradually carried through the arms and back, leading to overall weakness.

CRS confirmed a pre-existing unease regarding the Chinese people during that time. Although MSG is also commonly used by manufacturers of processed foods like Doritos and KFC, it is inextricably tied to Chinese food. The consequences of CRS remain today, as demonstrated in my research, virtually almost all soy sauce bottles in the US have some sort of reduced sodium or no-MSG identification.

This project has taught me to appreciate the authenticity rather than the convenience of an international food. Culinary culture is a public domain in where everyone has the right to access or own it. Yet grocery stores need to remember that culture cannot be separated from tradition. It has to be respected. From the item’s placement in a store and on shelves, to its surroundings and design, more stores need to pay tribute to the culture from which their products migrate. Essentially, mixing caramel coloring, preservatives, and water is not Asian cuisine. And on that salty note, I sign off.

-- Caitlyn Phung

References

Liu, H. (n.d.). Who Owns Culture? In From Canton Restaurant to Panda Express: A History of Chinese

Food in the United States (pp. 128-145). Rutgers University Press.

Germain, Thomas. A Racist Little Hat: The MSG Debate and American Culture. Columbia Undergraduate Research Journal. 2017; 2:1. doi: 10.7916/D8MG7VVN

Stein, E., & Shibata, M. (2019, February 26). Is Japan losing its umami? Retrieved April 20, 2019,

from http://www.bbc.com/travel/gallery/20190225-a-750-year-old-japanese-secret

#authenticity#tradition#resepct#culinarycuisine#education#empowerment#encourage#commodity#MSG#reducedsodium#healthy#glutenfree#marketing#surroundings#aisles#international#asianfood#asian#Japanese#Chinese#cuisine#soysauce#soy#365#WFM#WholeFoods#foggybottom#gwu#HanaMarket#Safeway

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spill the Tea: Are Millennials Killing the Coffee Industry?

Worldwide, tea is the second most consumed beverage, behind water (Macfarlane and Macfarlane 2004). In 2016 there were about 6 million tons of tea produced, with 40% produced in China and 22% in India (FAOSTAT 2017). However, these countries are not the leading consumers per capita. Turkey consumed 6.96 pounds of tea per capita in 2016. Ireland and the UK were in the second and third places, China was 20th, India 28th and the United States 35th, consuming only 0.5 pounds per capita (Quartz 2016).

In 2015, YouGov reported that while the average American drank 46 gallons of coffee in 1946 and only 23 gallons in 2013, tea consumption rose 20% in between 2000-2014. YouGov also reported that younger generations are starting to prefer tea over coffee. While I don’t think that drinking less coffee or preferring tea to coffee means that millennials are shunning coffee, there is clearly a huge demand for tea worldwide, so I wanted to find out what kind of variety stores have available in the US, and D.C. specifically. I have always preferred tea to coffee, and while I am usually disappointed at the variety available in cafes, I have never really paid attention to how many options available in grocery stores.

This class assignment required visiting five D.C. grocery stores and conducting optical research- basically just looking around without asking people questions- focusing on one product in those stores. I chose to look at the tea selection, specifically boxed or tinned dry tea whether it was bagged, loose leaf, or powder. All of these visits took place during the Spring 2019 semester.

For my first field visit, I went to the Whole Foods that is located on the campus of the George Washington University in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of D.C., at 2201 I St NW. Next, I stayed on campus and visited the CVS in the Shops at 2000 Penn, on Pennsylvania Ave NW. Moving north through Foggy Bottom, I went to Trader Joe’s, at 1101 25th St NW. I then went to Harris Teeter in the Adams Morgan neighborhood, at the intersection of 17th St NW and Kalorama Rd NW. Finally, I went to the Georgetown neighborhood and stopped in Dean & DeLuca, at 3276 M St NW.

The common thread through these locations is that they are all located in the Northwest section of the city. So, this should not be seen as an overview of the tea being sold in D.C. as a whole, but the tea being sold in this particular area. Northwest D.C. is an area that is popular with college students and tourists as it is home to many universities, the White House, Embassy Row, and many museums.

I discovered a wide variety of tea available in Northwest D.C. In every store I visited you will find a range of black, green, and herbal tea. Every store had caffeinated and non-caffeinated options. Brands like Lipton, Bigelow, and Twinings are stocked in multiple stores, except Dean & DeLuca. Every store except for CVS had at least one loose-leaf variety. Finally, except for in Dean & DeLuca, there was always at least one box or tin that marked the tea as organic and/or fair trade.

The pricing of the tea was fairly consistent across all five stores ranging from $3-$8 depending on the variety, brand, and quantity of the tea being sold. Of course, Dean & DeLuca is the outlier with prices from $10.50 to $45, because how can you prove you’re bougie if your average-sized box of tea didn’t cost more than a meal.

Across the stores, the target customer seems to vary. Due to their locations, Whole Foods, CVS, and Trader Joe’s are marketed more towards college students and young adults. Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s also seem to attract individual young professionals who may live in the area. Harris Teeter is located in more of a residential area, where cars are more popular than they are in other parts of the city. For this reason, Harris Teeter may be more popular for families doing weekly grocery shopping rather than individuals. Dean & DeLuca is in Georgetown, a high end neighborhood, and its clientele is likely more wealthy and more middle-aged or older rather than college students.

The target market of each store is reflected in the store’s layout and ambience. Whole Foods has a public image centered on organic products and the store shows that with natural colors, huge displays of fresh produce, and labels of ‘organic’ and ‘fair trade’ on almost all of the products, including the tea. CVS markets itself as a convenient stop to buy basic groceries or household items. The store has simple carpeting and shelving, and they don’t stock a wide variety of tea. Bright yellow tags help customers locate the items that are on sale and may be cheaper than other options. Trader Joe’s decorates each store tailored to the location. The one I visited had D.C. and GW specific decorations. Most products get a little blurb about what they are and what they can be used for, helping give a direct producer to consumer vibe to the company. Harris Teeter is the closest to what would be considered a supermarket. They have long aisles, full-sized shopping carts, and a wide variety of options for tea, perfect for anybody to find what they want. Dean & DeLuca’s upscale identity is definitely bolstered by the white walls, stone floors, and employees dressed as chefs.

In every store tea is located in the same area as coffee, either across the aisle from or directly next to each other. This makes sense, as both tea and coffee are popular breakfast drinks. I was usually able to find sweeteners right next to the tea or coffee, except for in Harris Teeter, where sugar was separated from the coffee by a selection of cooking oils. I still haven’t figured out the tea/beef jerky combination. Work on your upselling, Harris Teeter. The relative location of this aisle in each store varied. In Whole Foods, CVS, and Harris Teeter the aisle was vaguely in the center of the store. In Trader Joe’s and Dean & DeLuca it was towards the entrance of the store.

A store’s layout directs the customer to what they are looking to buy, while the product labels entice the customer by showing why that product is the best choice. For tea, this usually involves promoting taste, health benefits, and potential socioeconomic benefits. While some boxes of tea in most of the stores promoted being fair trade, the cultivation and production of tea present some serious concerns. Sarah Besky, in her research on tea plantations in India, explains the problem with fair trade labels and what she calls the ‘agrarian imaginary’. Fair trade labels promote the idea that some of the consumer’s money is going towards improving the livelihoods of plantation workers. The money, however, is usually just given to the plantation owners, who can use it as they wish. An agrarian imaginary refers to the idealization of the plantations as farms being worked by individuals who care about the land, rather than a colonial labor system that exploits the workers (Besky 2013). These concepts were especially apparent on the boxes of Tulsi tea in Whole Foods. This packaging featured an idyllic landscape and a picture of a person, who the customer is meant to view as the person who cultivated the tea that they are going to buy.

If you still care deeply about buying organic, fair trade tea, you can find plenty of options at Whole Foods in Foggy Bottom. For convenient, basic tea, go to CVS. If you are a Trader Joe’s loyalist, they have plenty of options. When you want a wide variety of brands and flavors, Harris Teeter has got you covered. None of these stores are significantly more expensive than the others. If you want to feel fancy, but also be broke, go to Dean & DeLuca. Maybe tea will always take second place to coffee in the minds of Americans, but that does not seem to have stopped companies from supplying a wide variety of options for shoppers. It’s probably safe to say that neither hot beverage is going away any time soon.

--Victorya Dube

Besky, Sarah. The Darjeeling Distinction: Labor and Justice on Fair-Trade Tea Plantations in India. University of California Press, 2013.

FAOSTAT. World tea production in 2016; Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity from picklists. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division, 2017.

Macfarlane, Alan, and Iris Macfarlane. Green Gold: The Empire of Tea. The Overlook Press, 2004.

Moore, Peter. Coffee's millennial problem: tea increasingly popular among young Americans. February 25, 2015. https://today.yougov.com/topics/lifestyle/articles-reports/2015/02/25/coffees-millennial-problem.

Quartz. Annual per capita tea consumption worldwide as of 2016, by leading countries (in pounds). 2016. https://www.statista.com/statistics/507950/global-per-capita-tea-consumption-by-country/.

#tea#green tea#black tea#herbal tea#loose leaf tea#lipton#bigelow#twinings#tulsi#whole foods#cvs#trader joes#harris teeter#dean & deluca#organic#fair trade#bougie#bujee#agrarian imaginary#marketing#upselling#grocery stores#dc#foggy bottom#west end#adams morgan#m st#anthropology#optical research#anth4008

0 notes

Text

I’ll Stop the World and Melt with You

I really screamed for ice cream these past few months in Washington, D.C.! Choosing ice cream as the subject for optical research and fieldwork was a sweet one. By paying attention to the location of the ice cream sections, the types of customers visiting the store and the section itself, the branding, and pricing, I learned a lot about ice cream’s place in a grocery store as well as what establishments will do to market certain items for the general population. In my five different field visits, I explored Whole Foods in Foggy Bottom, Trader Joe’s in West End, Foggy Bottom Grocery on the George Washington University campus, CVS Pharmacy in Foggy Bottom, and Gallery Market on GW’s campus. Although my research was inductive, there was a commonality that I retroactively focused on while visiting the five different stores: pricing and what it means for marketing.

Every store besides the CVS Pharmacy on E Street Northwest carried mostly pints of ice cream. I did not come across many larger sizes except when I ventured right off campus to CVS. There, I found reasonably priced tubs of ice cream for six dollars, the same price as the smaller pints. In the other stores, I only found pints that ranged from five to seven dollars each, a high number for the amount of ice cream. The price was dependent on the place and its location; for example, the most expensive pints were located at Gallery Market which is in the basement of a residence hall on campus. I found that this was most likely due to the fact that they have a monopoly over the student market: they know that people will shop here anyways because it is so convenient. Unlike a chain store like CVS, they can price things however they want.

In my study, I am making the claim that stores who only sell pints of ice cream are marketed towards single professionals living in the city. This is related both to the layout of the stores and to the ice cream selections. Whole Foods is not very stroller-accessible: to get to the main selection of food you have to either ride down an escalator or go down the stairs. The ice cream section had mostly pints and a few larger containers, but only one flavor so there was most variety with the pints. Trader Joe’s is more compact, and did not have a great ice cream selection. I went at a busy time, so it is possible that they might have a better selection at a time when not as many people are shopping, but the open drawer freezer of ice cream did not have a lot of space for many more items, so I stand by my assumption that this store catered its ice cream to single people. Foggy Bottom Grocery is located in a townhouse, and you must walk up steep steps to get inside the little place. It is also marketed for students, as it is located right across the street from South Hall, a resident hall on GW’s campus and sells marijuana products, Juul pods, red solo cups, and ping pong balls. This wouldn’t be the place to take your young child to get some ice cream. CVS had the best selection of ice cream, as it was the further off campus. However, there still weren’t many big carts to shop with and it is located in a non-residential area on E Street near the Red Cross and the Foreign Service Association. Finally, Gallery Market only sold Ben & Jerry’s and Halo Top pints at the high price of seven dollars. Although unaffordable for students, this selection is definitely marketed towards them.

During my time conducting fieldwork, I thought a lot about the weather and how this might have affected how many people I saw buying ice cream, which was close to nobody. According to NDTV Food and Meher Rajput, a nutritionist at FITPASS, ice cream can make cold, flu, and infection symptoms worse. In the wintertime, these illnesses are more common, so they advise to stay away from ice cream during the winter and state that you should keep it away from children, since the sugar additives and phlegm-increasing dairy could be disadvantageous in the cold winter months.

In terms of the package sizes, I was shocked at the amount of ice cream I saw. It seemed as though the people in charge of stocking the grocery stores did not have an affinity for the frozen treat and only put the most basic flavors and brands out for consumers to purchase. According to researchers Metin Çakir and Joseph V. Balagtas and their study of package downsizing and customer reaction, people shopping in Chicago were found to be less responsive to package size than to price, so companies can get away with package downsizing more easily. Perhaps I am just more passionate than the average person in regards to package sizes and ice cream amount, but I found the package sizing too small. However, if people are generally more concerned with price, then stores like the ones I visited could get away with selling pints at higher prices if there is nothing else to compare it to: if there were bigger tubs of ice cream next to pints more often, then stores would have to sell the pints for less than they could if they only sold pints. Therefore, this could also be a ploy to sell more while taking up less space.

Performing optical research at five different grocery stores in Washington, D.C. was an experience that will help me to view grocery stores and specific food displays in a different way. I learned that the sizing, pricing, and location of a section is related to whom the store wants to market the products. In these five stores near GW’s campus, ice cream was marketed for the single person who is most likely a student. The people working in these grocery stores did not expect to sell to families or groups larger than two, and the sizing and pricing reflected this fact. Also, I learned that not as many people eat ice cream in the winter! Whether or not this is actually a healthy thing to do, I say that we shouldn’t discriminate ice cream by putting it into a literal box. Well, you know what I mean. Let’s make ice cream a year-round phenomenon! Who wouldn’t want this frozen treat just because it’s cold outside?

"Is It Safe To Give Your Children Ice Cream During Winters?" NDTV Food. January 11, 2018. Accessed April 22, 2019. https://food.ndtv.com/food-drinks/is-it-safe-to-give-your-children-ice-cream-during-winters-1797860.

Çakır, Metin, and Joseph V. Balagtas. "Consumer Response to Package Downsizing: Evidence from the Chicago Ice Cream Market." Journal of Retailing90, no. 1 (2014): 1-12. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2013.06.002.

#marissakirshenbaum#icecream#overview#fivesites#washingtondc#foggybottom#westend#wholefoods#traderjoes#foggybottomgrocery#cvs#gallerymarket#gwu#campus#gworld#expensive#pints#benandjerrys#halotop#anth4008w#opticalresearch#fieldwork#iscreamforicecream#culture#anthropology#food#overpriced#packagedownsizing#winter#nevertoocold

0 notes

Text

Pink Salt: A Tale of Ethical Consumerism

Halite. NaCl. Sodium Chloride. All alternative ways to say “salt.”

When I think of salt, I am reminded of its not-so-subtle tang. It’s not a flavor, but more of a taste, or perhaps a “mouthfeel” as the fancy food connoisseurs might say. In my own cooking adventures, salt is always an afterthought. It’s not an ingredient that I add to my grocery list when shopping for supplies for a new recipe. Salt is simply the one food item that always sits in my pantry, as a bottle seems to last for years on end. And even though I often forget about its presence in my kitchen, it’s the one ingredient that is utterly, absolutely, and unequivocally vital to making food taste good.

Historical Significance

Beyond its ability to transform bland food into an exciting symphony of flavors, salt is a critical component of the human food system. According to food technology experts, salt is a popular food preservative because “its capacity to reduce water activity values…in foods slows down or even interrupts vital microbial processes” (Albarracin et al., 2010, p. 1330). Salt, in other words, extends the shelf life of packaged and canned food products by inhibiting bacterial growth and keeping food fresh.

Throughout history, salt has been essential to survival among people everywhere. It has been used to preserve meats and greens, allowing such foods to be consumed in cold winter months when hunting and foraging are difficult. In this sense, the usage of salt as a preservative enhances food security by ensuring that purchased items remain edible, thereby reducing food waste and safeguarding economic investments in groceries.

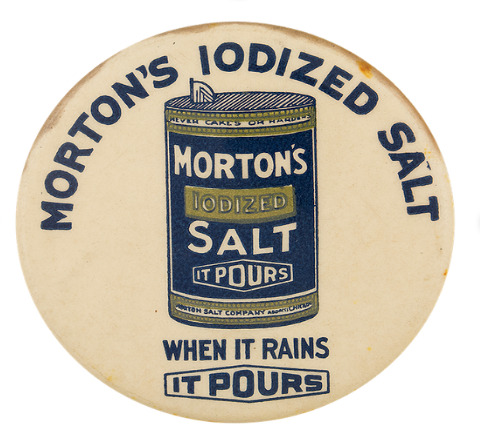

In addition to its success as a preservative, salt possesses numerous medicinal qualities. When cases of goiter—an “abnormal enlargement of your thyroid gland” often caused by iodine deficiency—spiked in the early 20th century, public health officials and medical doctors decided to add sodium iodide to salt in order to combat the epidemic (Mayo Clinic). Salt, in other words, was utilized as a vehicle for iodine delivery. In order to reverse the iodine deficiency, “iodized salt” appeared to be the “most practical” because “everyone used salt on a daily basis” (Markel, 221-223). Since iodized salt first appeared on grocery store shelves, the prevalence of goiter dropped dramatically. By infusing salt with medicinal and preventative properties, health officials enhanced salt’s significance in society.

Beyond its use in public health intervention, salt is an important cultural and religious symbol. According to anthropologist Iulian Moga, salt has been utilized by “the peoples of the Near East” as an “agent…in some incantations and magical or therapeutic rituals where…it acted as a purifying device by restoring potency” (2015, p. 21). In fact, salt has been so essential to mythology, economy, and symbolism that it was the subject of a 2015 conference in Romania, entitled “First International Congress on the Anthropology of Salt.”

Although salt may seem like a boring or banal ingredient to study, I chose it because of its abundance in nature and society. It’s difficult to quantify the numerous times humans interact with salt on a daily basis—through metaphors, food, skin care products, history (i.e. Salt Wars), and dozens of other areas, society is deeply intertwined with NaCl. Salt is not only a taste, but a theme in human life.

Now that I’ve surely piqued your interest in salt, I hope to shed some light on salt’s role in grocery stores in Northwest Washington, D.C. During spring 2019, I conducted optical research at five sites: Whole Foods, CVS, Trader Joe’s, Dean & DeLuca, and Safeway. During my data collection, I examined salt through an anthropological lens, which allowed me to analyze salt’s relationship to consumerism, culture, and economy. One limitation to my project is the methodology I used, as my research incorporates only optical observations, rather than interviews. Nonetheless, my project reveals important insights about local identities in Northwest D.C. and the social significance that salt carries.

Similarities

The placement of salt in stores across the five field sites was identical: salt was always in or adjacent to the spice aisle. Among the various seasonings, salt was never placed at eye level. At CVS and Dean & DeLuca, salt lived on the highest shelf, tucked away from the other ingredients. However, at Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, and Safeway, salt was mostly congregated on the bottom shelf. Because all stores confined salt to the less popular—and more difficult to reach areas—I’ve determined that salt is not a “hot ticket” item.

From my research, I’ve concluded that grocery stores are organized in a way that prioritizes profit margins. Exciting and new items are always at eye level, as grocers want these goods to pop off the shelf and into a customer’s cart. Since salt is always tucked away, it seems as though stores do not intend to advertise these items. This relative neglect is likely due to the fact that salt is a shelf-stable commodity and a little goes a long way. Whereas consumers may want to try new types of produce, cereals, and beverages, salt is a mainstay item that lasts the test of time. It does not need to be replenished routinely, meaning that customers aren’t often buying salt on their weekly grocery trips.

In every store in my study, salt is near its soulmate: pepper. This dynamic duo stands close by on the shelf, as if grocers advertise it as a package deal. The relationship between the two seasonings likely relates to their importance in cooking, as both commodities are common ingredients in American recipes (if you don’t believe me, watch some cooking shows). In CVS, salt and pepper came in a twin pack, cementing their importance to one another.

(Top: Safeway, Left: Dean & DeLuca, Right: CVS)

As a final point of similarity, each store carried Himalayan Salt. Even CVS—a no frills sort of place—had several of its Himalayan pink salt jars in stock. Even though this sort of salt variety has become popular, it is certainly more expensive than the standard, run-of-the-mill kosher salt. As I will later discuss, the universal presence of pink salt in my data reveals salt’s dynamic social status and represents important trends in consumerism.

Differences

The greatest difference in the five stores I visited was variety. CVS offered the most limited selection, followed by Trader Joe’s. The small selection of salt at these markets was relative to the size of the spice sections, as both had the fewest varieties available. Surprisingly, Safeway had the most abundant selection, including sodium-free salt, boxed salt, and salt flakes. The second-best option for variety was Whole Foods which offered Celtic Sea Salt and a diverse set of packages. Although Dean & DeLuca had a modest selection of salt, its options were not the most gourmet or “bougie.” Even though Dean & DeLuca carried matcha salt, it lacked the salt flakes and imported varieties that Whole Foods and Safeway displayed.

The labeling at Dean & DeLuca was refined and homogenous. The salts were packaged in small glass and tin jars, with delicate labels in white, grey, and other natural tones. The lettering on these options was more ornate in comparison to the other stores. Trader Joe’s offered only salts of its own brand with labels that matched the store’s simple, effortless vibes.

Both Safeway and Whole Foods carried a wide variety of labeling and marketing strategies. These stores also had the most diverse price ranges for salt, with large boxes of kosher salt and small, fancy varieties. The cheapest salts were contained in cardboard packages with bright colors and large, clear typeface. In contrast to these ordinary varieties, the more expensive options came in glass jars and had refined colors and lettering. This broad variety is proportional to the size of the store, since Safeway and Whole Foods are both supermarkets, whereas the other stores are smaller grocers.

The orderliness and tidiness of the sections also widely varied. The salt selection at Whole Foods was badly arranged, as all options—especially the lower-priced ones—were poorly stocked. The labels faced the back of the shelf, and the entire selection looked uninviting. CVS was similarly unkempt, while the three other stores were beautifully organized. See Whole Foods on the left and Dean & DeLuca on the right:

Conclusions

My field work reveals a fascinating anthropology of salt, especially in regard to its social significance. From my five field sites, I found a clear dichotomy between craft salt and ordinary salt. Since the less expensive varieties were displayed closer to the floor at Whole Foods and Safeway, these grocers attempted to elevate the gourmet, artisanal items by bringing them closer to a customer’s eye level. Of course, the biggest surprise of my research was the universal prevalence of pink Himalayan salt.

In conducting my study, I’ve thought a lot about why Himalayan salt has such popularity. I realized that the packaging of pink salt does not advertise any health benefit or claim to be tastier than the standard salt varieties. The only explicit marketing tool utilized for pink salt was in Whole Foods, where the jar displayed an illustration of the snow-capped Himalayas.

Priced at $8.99, this jar’s depiction of mountains serves as an “imaginary” in its effort to portray the salt as natural, sustainable, and refined (Besky, 2013, e-book pg. 58). For just one dollar more, the same brand offered a “fair trade” version of the salt, adding to the image of ethical consumerism.

Because four of the five stores I visited did not advertise the pink salt as superior to the standard varieties, it is likely that shoppers in northwest D.C. carry

an implicit assumption that pink salt is high-quality. Included in this impression of quality is a belief that the item is healthier, more organic, and even more flavorful than non-craft options.

Grocery stores are aware of the social significance of items such as Himalayan salt and capitalize upon the “imaginary.” As such, Himalayan salt is an essential index of social status, as consumers in northwest D.C.—a wealthy area—likely associate it with green consumerism and healthy living. Such an association stems from social and cultural experiences, as the majority of stores did not promote the item in any way. The universal presence of pink salts speaks to the local identities of consumers, as well as trends in high-end stores that market craft items as superior to more industrialized goods.

Although salt is a basic commodity, its variation reflects cultural preferences and assumptions. My biggest takeaway from this field research: never underestimate the social significance of a material good.

-- Lauren Petersil

References

Albarracin, W., Sanchez, I., Grau, R., and Barat, J. (2010). Salt in food processing; usage and reduction: a review. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 46 (7), 1329-1336.

Besky, S. (2013). The Darjeeling Distinction: Labor and Justice on Fair-trade Tea Plantations in India. Oakland: University of California Press.

Goiter (2018). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/goiter/symptoms-causes/syc-20351829

Markel, H. (1987). “When it Rains it Pours”: Endemic Goiter, Iodized Salt, and David Murray Cowie, MD. American Journal of Public Health 77 (2), 219-229.

Moga, I. (2015). Salt and Related Agents in Curse and Benediction Formulas of the Near East. In M. Alexianu, R.G. Curca, and V. Cotiuga (Ed.) From the ethno-archaeology to the anthropology of salt: programme and abstracts. Iasi, Romania: Editura Universitatii. Pg. 21.

Clayman, A. Morton Salt Company, est. 1848. (2019). Made in Chicago Museum. Retrieved from https://www.madeinchicagomuseum.com/single-post/morton-salt-co

#salt#NaCl#tablesalt#koshersalt#imaginary#saltflakes#pinksalt#bougie#boujee#safeway#wholefoods#wholepaycheck#cvs#deananddeluca#traderjoes#grocery#shopping#washingtondc#research#anth4000W#culture#anthropology#laurenpetersil

0 notes

Text

The Mystery of Non-Dairy Milk: Is It Really a Milk?

Non-dairy milk is a plant-derived beverage product that people usually consume as a milk substitute. Non-dairy milk could be made from various types of plants such as traditional soy and almond, as well as from the more “hip” plants like hemp and macadamia nuts. People choose non-dairy milk over the traditional dairy milk for different reasons. Many people like myself, we don’t really have a choice since our body is incapable of digesting lactose. For many others, non-dairy milk is a good milk substitution because of its dietary and environmental benefits. In fact, non-dairy milk is making customers, investors and legislators raise their eyebrows recently because of its quick-gaining popularity.

Traditional milk consumption has a long history in the US. Stemming from the colonial period, the European immigrants carried with them the traditional milk diet to the US. Before then, the Native Americans consumed very little to no dairy milk. Over years of development, there is a normative notion of drinking milk that is hammered into the American’s mind. This norm comes from the avid advertisement from the US very own government. The FDA and FTC encourage citizens to consume milk daily because of its benefits to “fuel” physical activity and improve athletic ability, among all the other advantages that milk can give (Wiley 2014, 46.) However, this obsession with milk seems to have taken an unexpected turn.

Over the year of 2018, milk sales in the U.S. dropped $1.1 billion and non-dairy alternative sales are expected to rise from $12 billion to $34 billion in the next 5 years (Sitzer 2019.) This growing trend raises the question: what is making customers choose non-dairy products over milk?

Over the past few months, I visited 5 food stores in D.C. searching for non-dairy milk. These stores include Whole Foods at Foggy Bottom, Trader Joe’s on 14th , Safeway on 17th, CVS on 17th and Dean and DeLuca on M Street. With that question in mind, I’m hoping to find out how non-dairy milk rose to the scene so quickly through investigating my non-dairy experience in D.C.

Labeling Wars

Looking at the expected growth in non-dairy milk sales, the milk industry has begun their moves in this battle with the customer’s new favorite. A bill (SB 39) filed by state Sen. Francis Thompson is attempting to prohibit the labelling of non-dairy products as “milk” (Duchmann 2019.) According to Kleinpeter Farms Dairy, this bill is actually beneficial to the consumers as they believe most consumers don’t understand the health concerns that come with non-dairy. They claim that consumers would confuse the health benefits of dairy milk with plant-based beverages and this is hurting citizens’ rights as a consumer.

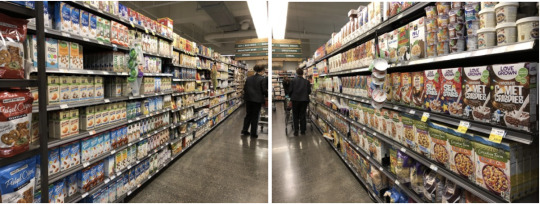

Throughout my non-dairy journey in D.C., I found out that only Trader Joe’s completely avoids labelling their non-dairy products as “milk”. Instead of saying soymilk or almond milk on their packaging, Trader Joe’s own brand non-dairy milk labels itself as a “beverage.” At Trader Joe’s, I was able to find an amazing selection of non-dairy products at a very fair price. The selection comes in new flavours that I’ve never seen before such as lavender blueberry or matcha almond milk. Though it was a busy day when I went, the shelves were still relatively well stocked. The wide selection and the beautiful display show that it is an important product at Trader Joe’s.

In comparison, Whole Foods also has a large variation of non-dairy milk and provides own-brand non-dairy products. The first picture shows a general view of the aisle where the non-dairy is at Whole Foods. On the left, the non-dairy milk occupied two full shelves and provided a wide array of products, ranging from soymilk to the more rare macadamia milk. At eye level, I found the Whole Foods brand non-dairy milk. Though the main product label still says “Soymilk” or “Rice Milk” in large and eye-catching font, there is a smaller label underneath it that clarifies the product as a “beverage.”

This strategy used by Whole Foods, and many other generic brands comparing to Trader Joe’s, could be because customers might be more inclined to buy products that they are more familiar with. We have been broadly using terms such as soymilk and though changing the label doesn’t change the products inside the package, people might still be more adapted to a certain “nostalgic” name like “milk”. So using the word “beverage” seems to only confuse the customers more and would only benefit the milk production companies.

New Craze over Non-Dairy Milk

In recent years, more and more people in the US are embracing the benefits and diet of non-dairy milk. Besides the extreme sales growth, the market is also coming up with a larger variation of products. In 2018, the new oat milk product Oatly came to market and led to a shortage so great that a case of oat milk was sold for $200 and more (Houck 2019.) I did manage to try this brand out before writing this review and I have to be honest, it was rich and flavourful. So viscous that it gives the same satisfying feeling of drinking milk, and so beautifully sweet that it goes with everything.

Other start-ups quickly followed this new growth in market and came up with new methods such as using fermented yeasts to make non-dairy milk. Before this blooming period of non-dairy sales, I remember only seeing the most generic brands such as Pacific or Almond Breeze in the non-dairy section in supermarkets. Now when I walk into the store, I always need to pause and think about which new products I want to choose. This wide range of products reflects the customer’s fast growing demand for non-dairy milk and that they are willing to pay to try the newest products. However, not all the stores I visited caught up with this trend quite as well as Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods.

In both Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods, I saw at least two floor to ceiling, well-stocked shelves of non-dairy milk neatly displayed around the breakfast food aisle. It was easy to find and encourages people who plan on buying some cereal for breakfast to opt for non-dairy products. These stores not only provided a wide array of products like mentioned above, they also gave a very good price, starting mostly at $1.5. This way, customers have more liberty to actually choose the items they want to buy instead of being limited by the store’s marketing strategies.

To my surprise, Safeway as one of the supermarket giants, had a limited selection of non-dairy milk when I visited the store on 17th Street. As seen in the picture on the right, most of the products were from generic brands such as Almond Breeze and indeed most of the non-dairy milk Safeway carried was also almond milk. The display was a bit disheveled as well. Not only most of the products were out of stock, the non-dairy milk also shared the shelf with packaged milk. At eye level where products were most easily seen by customers, there were some of the most expensive non-dairy milk starting at $4.

Worse than Safeway, I had the most unpleasant time at CVS and Dean and DeLuca when I was looking for non-dairy milk. For CVS, I did not have any expectations when I went in given that it is afterall a pharmacy. However, I still only found 4 types of non-dairy milk from 2 different brands, Almond Breeze and Silk. Not only the display was miserable, mixing in with all kinds of beverages such as milk and orange juice, the price was also extremely unfriendly. Most of the products started at $4.99 for a carton of generic non-dairy milk. At the back of the store hidden away from all foot traffic, I found one single box of smaller sized almond milk, priced at $2.79 as well.

But for Dean and DeLuca, I had high hopes as it is known for its bougie products and fancy selections. To my disappointment, the selection at Dean and DeLuca was not any better than CVS. Though the shelf was well-stocked and nicely displayed, the variation at Dean and DeLuca consisted of only original soymilk and almond milk. The only advantage they had over CVS is that the price was more fair than that of CVS, starting at $3.5 for the exact same products that CVS had. However, as an actual food store, Dean and DeLuca fails to even compete with the standard that Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods set.

From this comparison of variations and pricing between stores, I found that Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods are more inclined to catch up with the growing trend of non-dairy milk. One of the reasons customers prefer non-dairy milk over regular milk is that more people become aware of the environmental impact that milk production carries (Sitzer 2019.) A study by University of Oxford found that producing a glass of milk emits 3 times more greenhouse gas than milk alternatives such as plant-based beverage (Sitzer 2019.) This might be one of the driving force for the rapidly growing non-dairy demand among customers.

Stores like Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods are known for their distinct brand strategies. Trader Joe’s is your hip, neighbourhood food store that takes into concern of customer’s needs and feelings. From the mural I saw right after I entered to the handwritten price tags, I felt that Trader Joe’s is customer-friendly and is willing to change based on customer’s interests. Likewise, Whole Foods brands itself as an organic market, providing the most peculiar organic products. Organic products are not only better for consumption (arguably), they are also associated with a better environment because of the elimination of pesticide use. For these particular reasons, Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods seem to be open to adapting the new trend of non-dairy diet in the US in order to better present themselves in the market.